Archaeologist outsmarts thieves, the discovery of the Royal cache of Deir el-Bahari

Better than Indiana Jones, the true story of the Pharaohs' mummies' rescue from plunderers.

Dear reader, past stories have helped you walk in the footsteps of art historians.

There was choosing what to do when Nazis turn up in your museum. And a detective story trying to find the only genuine portrait of Leonardo da Vinci.

Here, we climb aboard the time machine and land in Egypt in the 1880s—not the Hollywood version, where scary mummies come back to life and Pharaohs curse archaeologists. The real one.

Our hero—this is you, dear reader—is French but works for the Egyptian government as the Director of Antiquities. Your name is Gaston Maspero, and, needless to say, you can read hieroglyphic inscriptions fluently.

The Antiquities Service is barely 30 years old. Movies and Indiana Jones have not yet been invented. The first Egyptologists created a new science with each stroke of the pen and every bucket of sand shoveled.

On occasion, to save ancient treasures, their tools can be guns and cunning.

Your predecessor, Mariette, was told a Queen's tomb had been found intact. And that a local official unceremoniously threw away the royal mummy and gifted the Queen's jewels to his favorite ladies.

That enraged him, so Mariette rushed to the scene, not with a whip but with a pistol, threatening to shoot anyone stopping him from recovering the royal treasure.

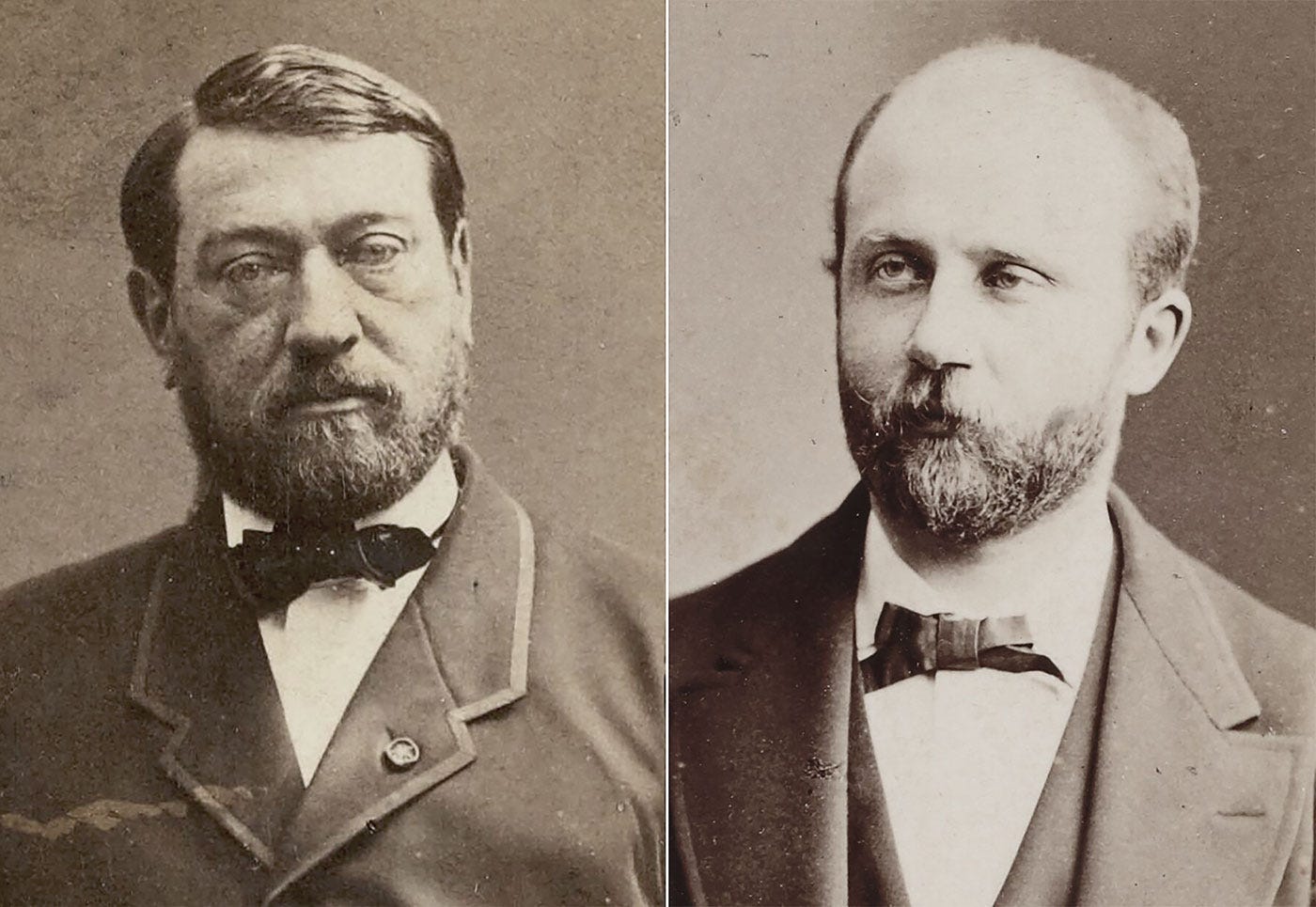

The man on the right, Gaston Maspero, is you, dear reader, in this story. We'll soon see his creative solution to recovering ancient treasures.

The man above, Pierre Montet, discovered three intact royal tombs filled with gold treasure at the start of the Second World War. It starts to look like the OG Indiana Jones, doesn't it?

Thieves discover the cache of the royal mummies

If you find Tutankhamun's solid gold sarcophagus and mask impressive, remember that he was a teenager, and his tomb is tiny compared to other Pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings.

His burial was so rushed that there was not even time to let the plaster on the walls dry.

So, imagine what treasures were held in the tombs of major Pharaohs. To give you an idea of the difference between legend and reality, let me give you some clues about tomb theft in ancient Egypt:

- Tombs have been discovered intact, but with mummies already relieved of their treasures. The embalmers took their riches before burial...

- Tutankhamun's tomb is not intact, as it was twice ransacked by thieves soon after it was sealed shut.

- Ramses III's tomb was visited by thieves only twenty years after his burial.

What happened to the tons of gold treasure will be told in a future story. This is to help you, dear reader, appreciate that after three millennia of looting, 99,98% of Pharaoh's treasures were looted, and ponder the odds that anything may be found.

Hiding place of Egyptian Kings left untouched for 3,000 years

The problem with mummies being covered in gold is that it was the best incentive for plunderers to burn or shred them. And what matters for an ancient King is the survival of his body, one of the most essential conditions for eternal life.

Three millennia ago, the high priests of Luxor decided to hide as many royal and priests' mummies as possible from thieves. The hideout they picked was so well chosen that it remained untouched for three millennia.

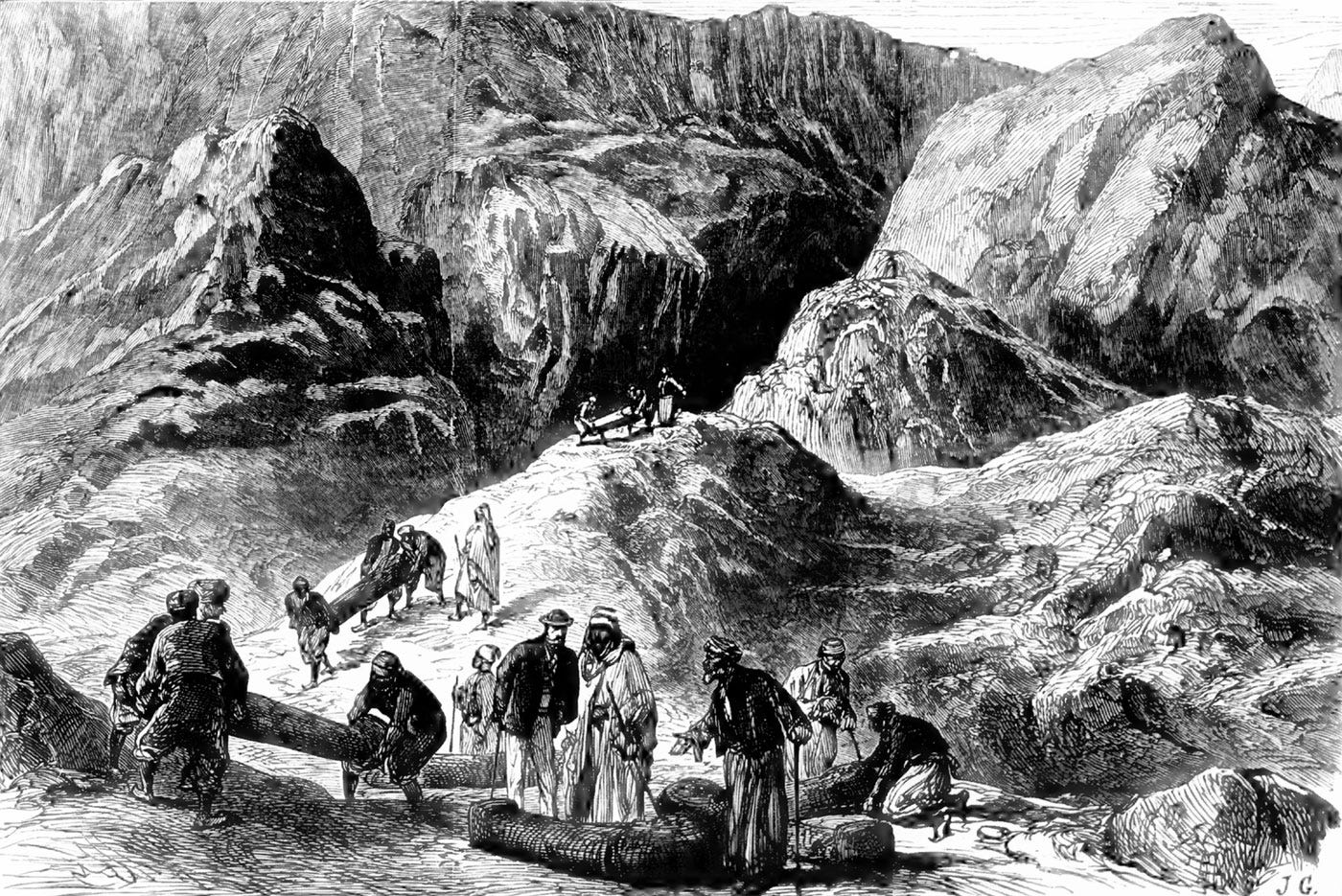

See the photo above, and just on the left, imagine a bottomless hole inside the cliff. Behind is the Valley of the Kings, and for millennia, thieves have combed the mountain, leaving only a handful of untouched treasures.

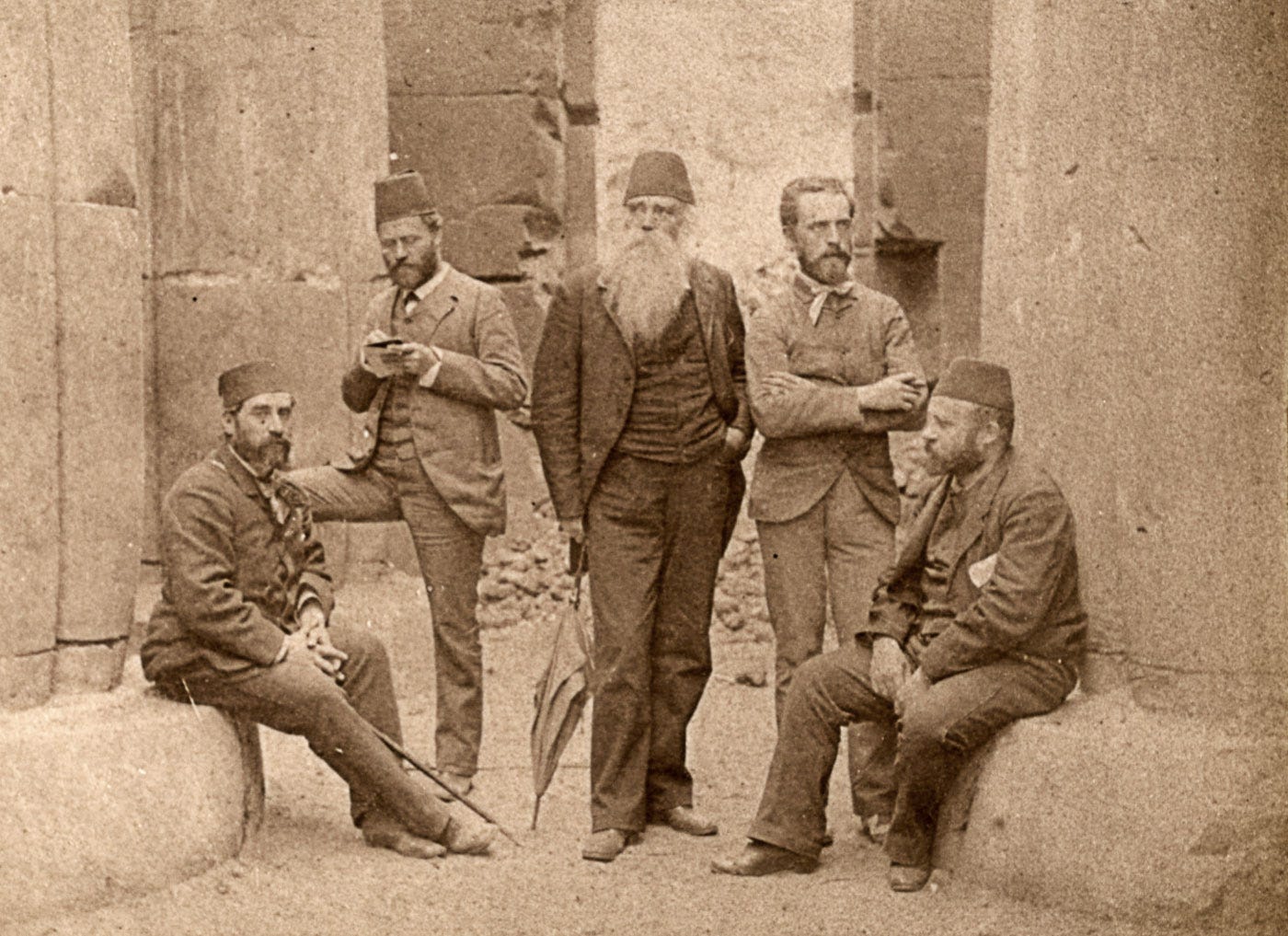

When you were the Antiquities Service director in the 1880s, this majestic temple looked like a pile of ruins. A village sits on top of tombs, explaining how tomb looting was an ancient tradition. The most infamous in this trade was the Abd el-Rassul family.

Ten years before our story started, they discovered the jackpot while searching for a lost goat along the cliff near Hatshepsut's temple.

A deep shaft led to a corridor with dozens upon dozens of sarcophagi, some of which had a cobra on their head. Any good plunderer knew what that meant: Pharaohs.

Ramses II and Thutmose III shared a deep corridor with Kings, princes, Queens, and priests. The Abd el-Rassul clan acted cleverly: they only visited under the cover of darkness and kept their discovery a secret.

Hoping no one would notice, they sold small objects and papyrus rolls to tourists and antique dealers piece by piece. Dear reader, you are Maspero, and you can read ancient Egyptian, so now's the time to outsmart thieves.

Cat and mouse game between thieves and Egyptologists

You keep an eye on the antiquities market in Egypt and Europe. You notice names and inscriptions and start to put two and two together: the villagers of Luxor have made a significant discovery of royal and priestly tombs.

The problem you have is to find where they found these. It is not like you turn up in the village and ask questions. No one wanted to give up the golden goose, so a game of wits between thieves and Egyptologists started.

American Egyptologist plays the part of the wealthy buyer to hook thieves

While Mariette resorted to the threat of violence, you, Gaston Maspero, used honey to attract bees.

Who can resist the sweet smell of an eager American collector with deep pockets? That is the bait Maspero dangled over the heads of the Abd el-Rassul family.

The big cheese has a name, Charles Edwin Wilbour, an American fluent in French whose Egyptology professor was you, Gaston Maspero. With his bushy beard, Wilbour acted as a wealthy collector, buying his way to the source of stolen goods, the Abd el-Rassul brothers.

Cunning worked to hook the thieves, but not to make them talk. Maspero, as director of the Antiquities Service, requested the arrest of the brothers, who were brutally questioned.

Maspero wrote

For two months this man lay in prison, obstinately silent; and I just left, when, prompted by jealousy and avarice, one of his brothers decided to tell all.

In this wise we were enabled to put our hands, not upon a royal tomb, but upon a hiding place wherein were piled some thirty-six mummies of Kings, Queens, princes and high-priests.

Rumors of a gold treasure about to slip away flared villagers' tempers, and archaeologists working for Maspero worried they would be attacked. They had to rush.

In only 48 hours, at the height of summer, they extracted all coffins from the cliff and brought them to the Nile. One coffin was so big that it needed to be carried by sixteen men.

Whoever has visited a royal tomb in scorching heat can imagine the lack of air and the profuse sweating.

It was far worse, finding yourself in a narrow underground corridor holding a candle, surrounded by highly flammable material—mummies covered in resin and dry wood—while fearing that armed bandits were waiting for you outside.

A scene that seems to be straight from Hollywood, but is authentic

As if you were standing by the Nile in 1881 when boats collected the royal bodies to ship them to Cairo, here is a first-hand account of what the scene looked like:

Already it was known far and wide that these kings and queens of ancient time were being conveyed to Cairo, and for more than fifty miles below Thebes the villagers turned out en masse, not merely to stare at the piled decks as the steamers went by, but to show respect to the illustrious dead.

Women with disheveled hair running along the banks and shrieking the death-wail, men ranged in solemn silence and firing their guns in the air, greeted the Pharaohs as they passed.

Never, assuredly, did history repeat itself more strangely than when Ramses and his peers, after more than three thousand years of sepulture, were borne along the Nile with funeral honors.

Maspero reports the same view:

From Luxor to Quft, on the two banks of the Nile, dishiveled women followed the boat screaming, and men fired guns like they do at funerals.

That scene feels like it came straight out of a movie, but is genuine. It looked as if the mourners on ancient tomb walls stepped outside to pay a last homage to their Pharaohs. The only difference was the guns and the steam engines.

Dear reader, I trust this little journey down the Nile brought you a Moment of Wonder.

If you want to discover the real Indiana Jones story, when three intact Royal tombs filled with gold treasure were found at the onset of the Second World War, please mention it in the comments.

Sources

Gaston Maspero, “Rapport sur la trouvaille de Deir el-Bahari”, Institut Egyptien, bulletin n° 2; 1881. Les momies royales de Deir El-Bahari, 1886.

Amelia B. Edwards, Lying in State in Cairo, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, 65.386, 1882.

I would love to hear more please!