Art historians' minds against Nazi guns

The untold stories of bravery in the face of barbarity, saving the beauty of the world.

Dear reader, with the story of Rose Valland, the Art Spy, we wondered what we would do if it were 1940, we were an unpaid curator, and the Nazis turned up in our museum. We also discovered the quiet hero who organized the largest art rescue operation ever, Jacques Jaujard.

As director of the French museums at the onset of World War Two, Jaujard successfully saved not just the Louvre but two hundred museums' worth from Nazi theft and destruction.

Here, not only do we meet heroes never shown in films, but we will wonder if we would be as brave as they are.

We set the time machine to the summer of 1944, after D-Day. The Nazis are taking their revenge on defenceless civilians, burning and slaughtering their way back to Germany. We do not look like Hollywood stars, and we are only curators tasked with safeguarding the treasures of mankind.

Nazis point their guns at us. They are about to torch the Venus de Milo, the Victory of Samothrace, and Michelangelo's Slaves.

What would you do, dear reader? How do you stop them? This is not a movie, but reality.

Hiding museum treasures from Nazis

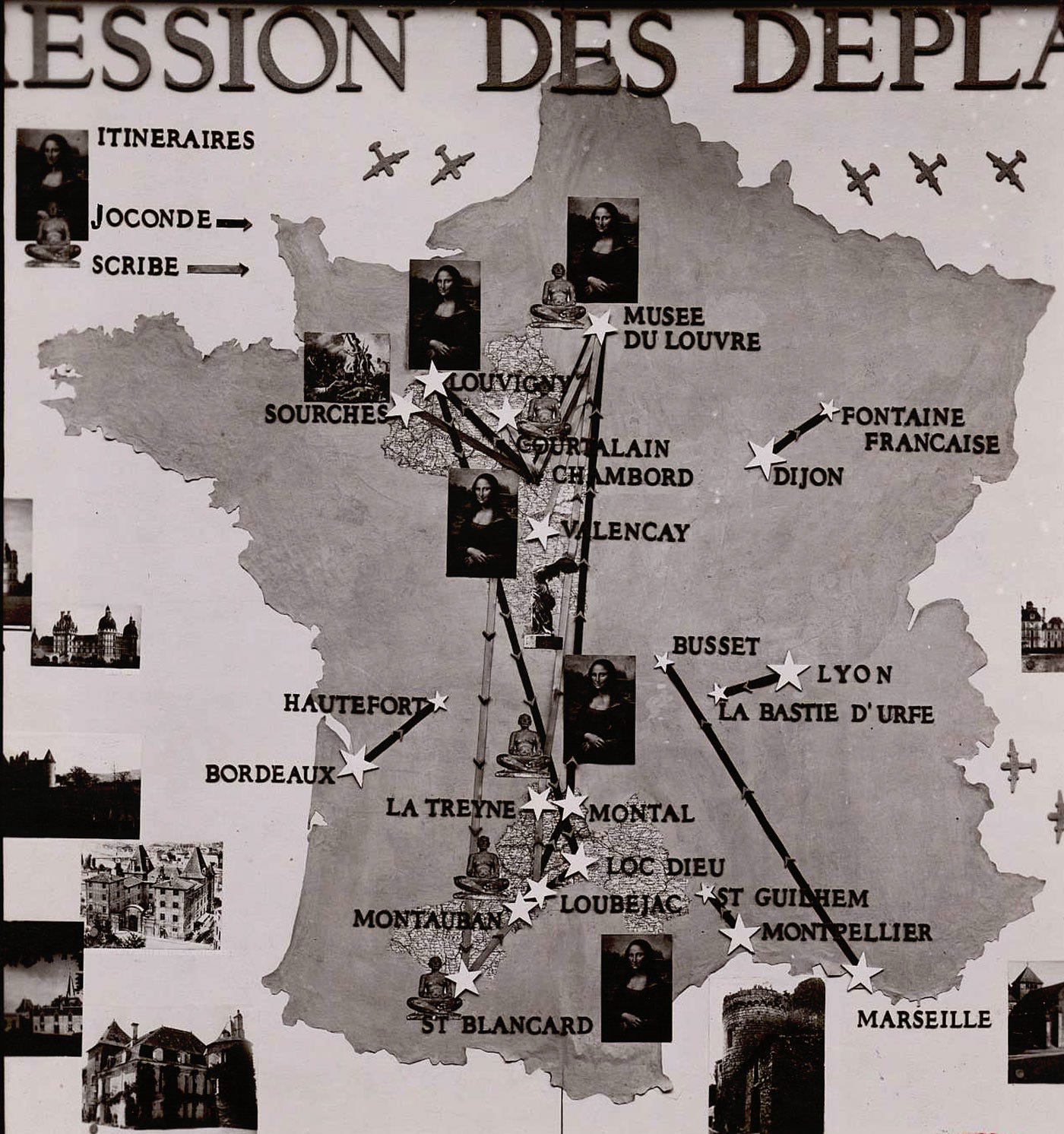

The map above shows the many travels of the Louvre's masterpieces during the Second World War. In the weeks before the German invasion, the Louvre—along with 200 museums, Versailles, and cathedrals' stained—glass windows—was emptied of its masterpieces.

But where are these treasures stored? In castles. Some belong to the state, and others are requisitioned from their private owners. Why castles? It is not that there are 40,000 castles in France, but that they are in the countryside. Cities are usually attacked by planes, not castles in the middle of nowhere.

Furthermore, their defensive nature, with massive walls, makes them ideal places to store artworks. Their large rooms make it easy to store large-scale paintings and statues and to set up security.

The Nazis knew where the museum treasures were stored

France was under occupation. At first, in theory, only the country's northern half was occupied, but soon enough, its entirety. From the start, the Nazis knew which castles held artworks and what was inside each.

The Kunstschutz, the German service in charge of protecting art, had the inventories, and its leader, Count Wolff Metternich, visited Chambord, the primary storage center, in person. But he acted like the art historian he was and protected museum treasures from Nazi plunder.

This is why he was sacked by his superiors and received the Legion of Honor after the war. In the Nazis' minds, it was just a matter of time before the museums or France were destined to end up part of the Third Reich. Fortunately, this never came to be.

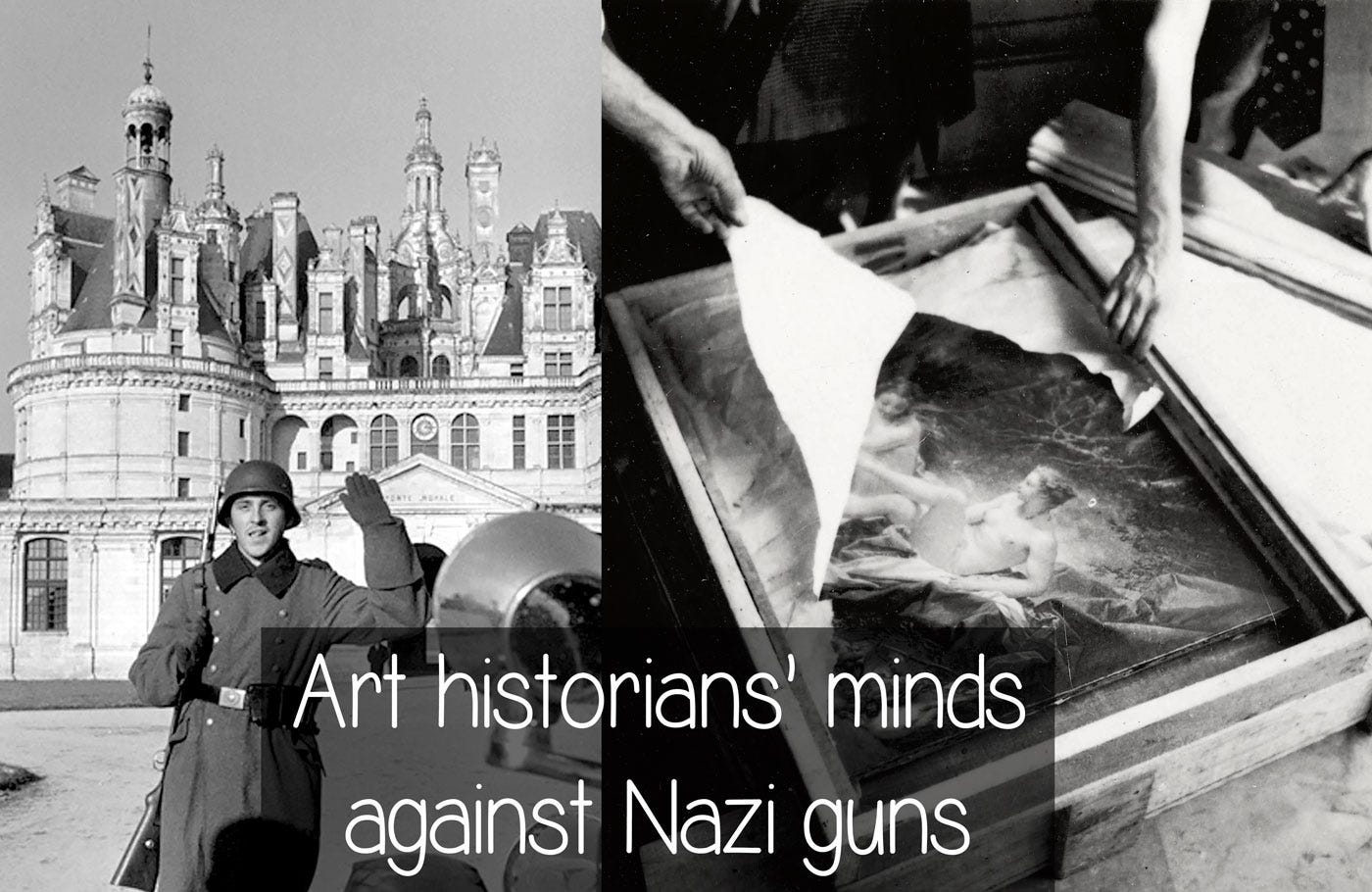

Chambord castle, the primary storage of museum treasures during the war

Over 40 castles were used to store museum treasures, but the main one remained Chambord. As visible in the photo above, museum guards and curators lived there during the occupation, in challenging conditions.

During these four years, curators and guards regularly conduct fire drills and even let paintings outside to dry them out from humidity. Heating was prioritized for the art collections. It is not an exaggeration to say that some curators slept beside artworks, particularly the Mona Lisa.

Thanks to Metternich, the state-owned artworks were not seized, but the private art collections stored in Chambord were. Then, from D-Day, there was a new risk, the Allied bombing.

This is why curators put signs in large letters on the castle grounds, easily visible to Allied pilots, to prevent accidental destruction of art treasures.

Heroes falling from the sky — Lieutenant William Kalan

In June 1944, a B-24 Liberator bomber flew from England to the South of Paris but was hit by German fire and was about to crash. As visible in the photo above, it crashed 100 meters from the castle.

Lt. Kalan steered the plane to avoid crashing into Chambord, miraculously saving his crew and parachuting himself and his copilot just in time. Local members of the Resistance sheltered both the pilot and copilot. Kalan, who spoke basic French, helped the Resistance before returning to the US Army.

William Kalan returned to Chambord for the first time in 1998. A memorial has been erected at the spot of the crash. In 2009, quite late, William Kalan, then 91 years old, received the Legion of Honor.

An emotional Lt. Kalan said, "I almost killed the Mona Lisa!" William Kallan passed away in 2017, aged 98.

Nazis threaten to burn Chambord and the masterpieces it contained

From June 1944, Nazi soldiers were making their way back to Germany and took revenge on civilians and members of the Resistance.

Warning: there is a gut-wrenching story next. Members of the Waffen-SS, Das Reich, burnt alive women and children inside a church. It was context to help you understand, dear reader, the sort of people we are dealing with.

Resistance fighters and Germans fought on the grounds of Chambord, killing one German. The Nazis took hostages, killing four, and burnt buildings in Chambord village and near the castle. Then made a clear threat:

The castle will be razed, the homes destroyed, the populace must pay!

Three men saved Chambord: Pierre Schommer, the curator; Abbé Gilg, the priest; and Brigadier Foeller. The last two spoke German, and pleaded with the Nazis to refrain from burning Chambord.

The priest insisted that he tended to German soldiers during the First World War. Since the Nazis toured the castle without finding weapons or members of the Resistance, they agreed to move on.

Looking at Nazi criminals in the eye — Gérald van der Kemp

Dear reader, now is the time to ponder what we would do if Nazis were pointing guns at us. We are curators or museum guards at the castle of Valençay. The Venus de Milo, the Victory of Samothrace, the Crown Jewels, Michelangelo statues, and countless masterpieces are inside.

A Das Reich column is on a punitive mission in revenge for the killing of German soldiers. They enter the castle, start lighting fires, and throw the curators and guards before a wall.

Here is the testimony of Gérald van der Kemp, the curator in charge, for the first time translated into English:

What was bound to happen one day did: two German soldiers were killed on the edge of the forest surrounding the castle, and in retaliation, the Germans decided to immediately shoot the curator—in this case, me.

I found myself, cane in hand, flower in my lapel, back to the wall, facing a firing squad ready to fire.

Meanwhile, someone had already set fire to the castle.

I then addressed the officer commanding the squad: "Monsieur, if Valençay burns, the catastrophe will be as serious as the fire at the Library of Alexandria!"

The officer replied: "Monsieur, we are not here to discuss art history!"

I then asked for an interpreter, fearing that the officer might not have understood me properly.

The interpreter arrived. I told him briefly about the fabulous collections that would probably burn in a few minutes. It was no use.

Then, exasperated, I began to shout:

"If Valençay goes up in flames, you will be shot within twenty-four hours! As will anyone who goes to tell Field Marshal Goering that all the treasures of French art had been lost in the flames!"

The officer and the interpreter turned pale. Marshal Goering, they hadn't thought of that! I was released immediately.

With the inhabitants of Valençay rushing to the scene in large numbers, I managed to bring the fire in the castle under control. It was about time. Engineers were already placing grenades under the furniture in the salons where I had stored the Guimet Museum.

It took two days to rescue Valençay, and for the curator to consider what he had just done:

I was seized by a retrospective panic that manifested itself in a violent trembling of every limb of my body.

Gérald van der Kemp later became the director of Versailles Castle and revived Monet's gardens at Giverny. He never bragged about his courage in saving the Venus of Milo, and there are no movies or TV documentaries to tell that story.

Does he look like a Hollywood hero? What about the curator, priest, and guard at Chambord? All of these men had Nazi guns pointed at them, and managed to save the treasures of mankind, not using guns, but their minds.

What would you do if you were in their situation? The same question can be asked with Rose Valland, who recorded Nazi crimes under their noses, or Jacques Jaujard who organized the most important art rescue operation ever organized.

They do not look like heroes and, like most real-life heroes, never said they were. This story was not brainstormed in a Hollywood studio. It is not AI make-believe or fiction; it is true.

I hope, dear reader, that discovering genuine acts of bravery in the face of barbarity was a Moment of Wonder.

Sources

José-Luis de Vilallonga, Gold Gotha, translated and adapted for this article by the author.

Photos Archives nationales.

https://don.chambord.org/crowdfunding/Tresors_de_guerre_39_45/page/21_22_aout_1944

https://don.chambord.org/crowdfunding/Tresors_de_guerre_39_45/page/crash_22_juin_1944

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/walnut-creek-man-gets-france-s-highest-honor-3205453.php