Peak Renaissance was quite different from what is shown on TV shows.

Only six years before our story starts, the people of Florence burned their 'Vanities'—their art masterpieces.

A preacher, Savonarola, convinced them that the Apocalypse was near:

[Savonarola] crying out every day from the pulpit that lascivious pictures, music, and amorous books often lead the mind to evil, became convinced that it was not right to keep in houses where there were young girls painted figures of naked men and women.

And on two occasions, they organized a Bonfire of Vanities:

The people were so inflamed by Fra Girolamo, that on that day they brought to the place a vast quantity of nude figures, both in painting and in sculpture, many by the hand of excellent masters, and likewise books, lutes, and volumes of songs, which was a most grievous loss, particularly for painting.

By 1504, Florence had been artistically wiped clean.

As it turned out, two of Florence's great sons had been spared the indignity of watching artistic wonders turn ashes.

Now, they both returned to Florence, ready to work.

One was in his early 50s, Leonardo. The other was in his late 20s, Michelangelo.

And the Republic needed to decorate the Palazzo Vecchio—City Hall.

City Hall Seeks Painters

What better way to restore Florentine pride than commissioning frescoes of its military victories?

What is fresco painting?

It involves applying fresh plaster to a wall and painting it while still humid. That is why fresco means 'fresh,' freshly applied plaster.

When moist, it sucks up the color applied to it, and as soon as it dries up—a question of hours—it is impossible to keep on improving the painting.

Hence, al fresco implies 'painting fast.'

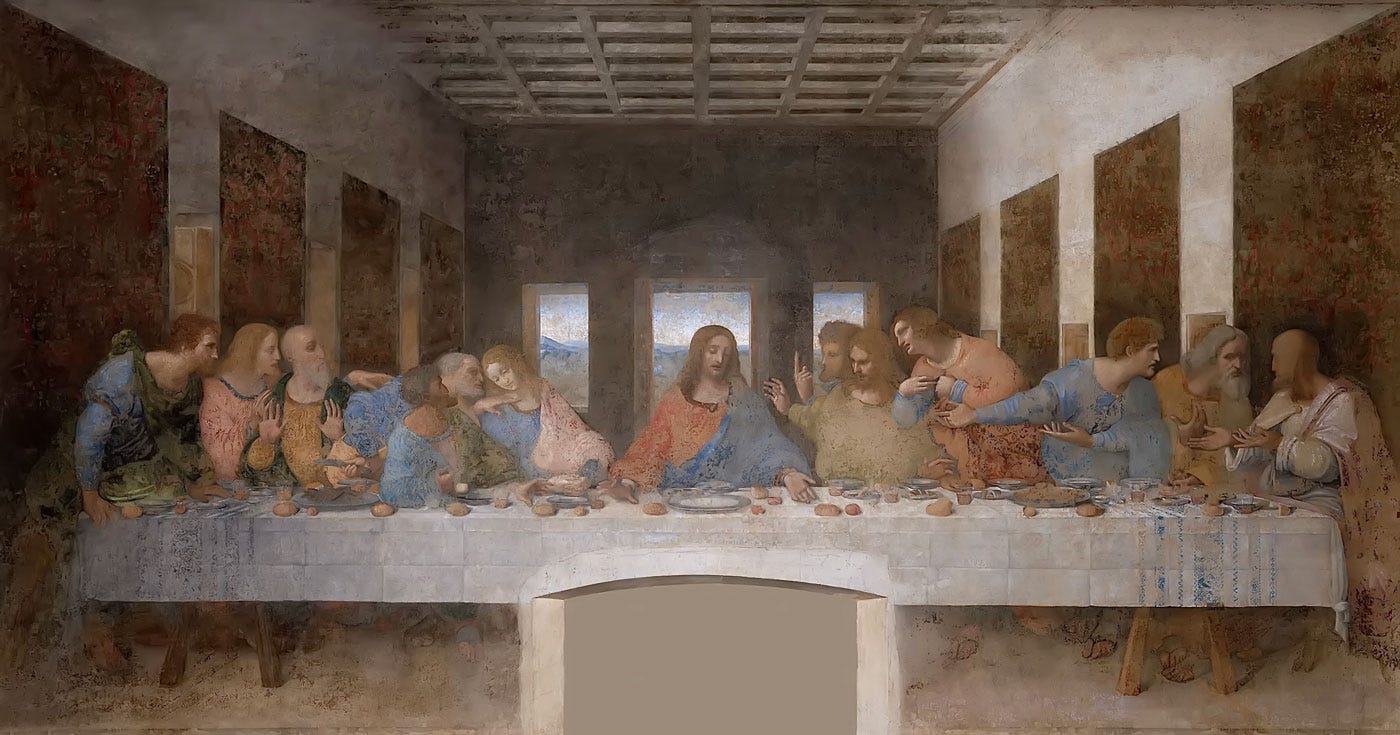

When he received the commission in Florence, Leonardo had some experience painting walls.

You may have heard of it: the Last Supper in Milan.

While the monks were not impressed—they cut a door right through the middle for a shortcut to the kitchen, hoping to avoid eating cold soup—art lovers were.

The Last Supper In Milan

It was astounding in its photographic quality and three-dimensionality.

If you have never seen the real thing, the photos do not do it justice. The figures are much larger than life.

The room is a rectangular canteen, so imagine being a monk seated perpendicular to Leonardo's painting, praying for your soup to arrive warm—Milanese winters are biting.

The room's perspective aligns perfectly with the painted walls, making it 'pop'—almost like a children's pop-up book.

The effect is uncanny and can only be experienced in person.

Waiting for lunch in that canteen meant sitting with Christ at the table, sharing the shock and horror his companions felt when they heard that one among them would betray him.

Leonardo, the slow-tempo Painter

Leonardo was many things, but being fast was not one of them.

He also had a reputation for leaving his paintings unfinished.

His trademark technique, sfumato, involved creating shading with layer upon layer of transparent darkness, using oil, which often took years of work.

For the Last Supper, a priest badgered Leonardo for looking at the wall rather than painting it.

The genius was searching in his mind as fresco painting obliged him to be fast, making it impossible to do his magic—slowly adding oil layers.

So, he experimented, creating an untested mix of egg-based tempera with oil on dry plaster.

When almost finished, the result took one's breath away.

To contemporary eyes, it would have felt like being in front of a larger-than-life photograph.

But as soon as Leonardo left the room, it began to flake away and has faded ever since.

You can compare the two images above, Leonardo's fresco original and the oil painting copy made soon after by one of Leonardo's pupils, to get a sense of what it looked like.

Yet, even as a faint shadow of what it was five hundred years ago, it still dazzles.

About Leonardo's slowness, his biographer explained that the painter's:

Constant search to add excellence to excellence and perfection to perfection was the reason why his work was slowed.

Leonardo work for the Palazzo Vecchio

His reputation for not finishing what he was paid to do preceded him.

The contract giving him the job of painting one wall of the City Hall even had a clause for that:

And in the event that the said Leonardo shall not, in the stipulated time, have finished the said cartoon [we] can compel him by whatever means appropriate to repay all the money received in connection with this work.

That’s not even worrying about the painting, but the preparatory sketch—the cartoon—being completed.

So, the clever solution was to speed him up by introducing another rooster into the room—a younger one named Michelangelo.

Two Roosters In One Coop

Thus began the Artistic Fight of the Century, fought with brushes instead of boxing gloves.

A generation younger, Michelangelo's style contrasted sharply with Leonardo's.

Michelangelo's figures were muscular, manly, dynamic, and often nude.

Leonardo's figures were graceful, androgynous, and svelte, usually smiling gently.

He worked slowly, whereas Michelangelo worked swiftly.

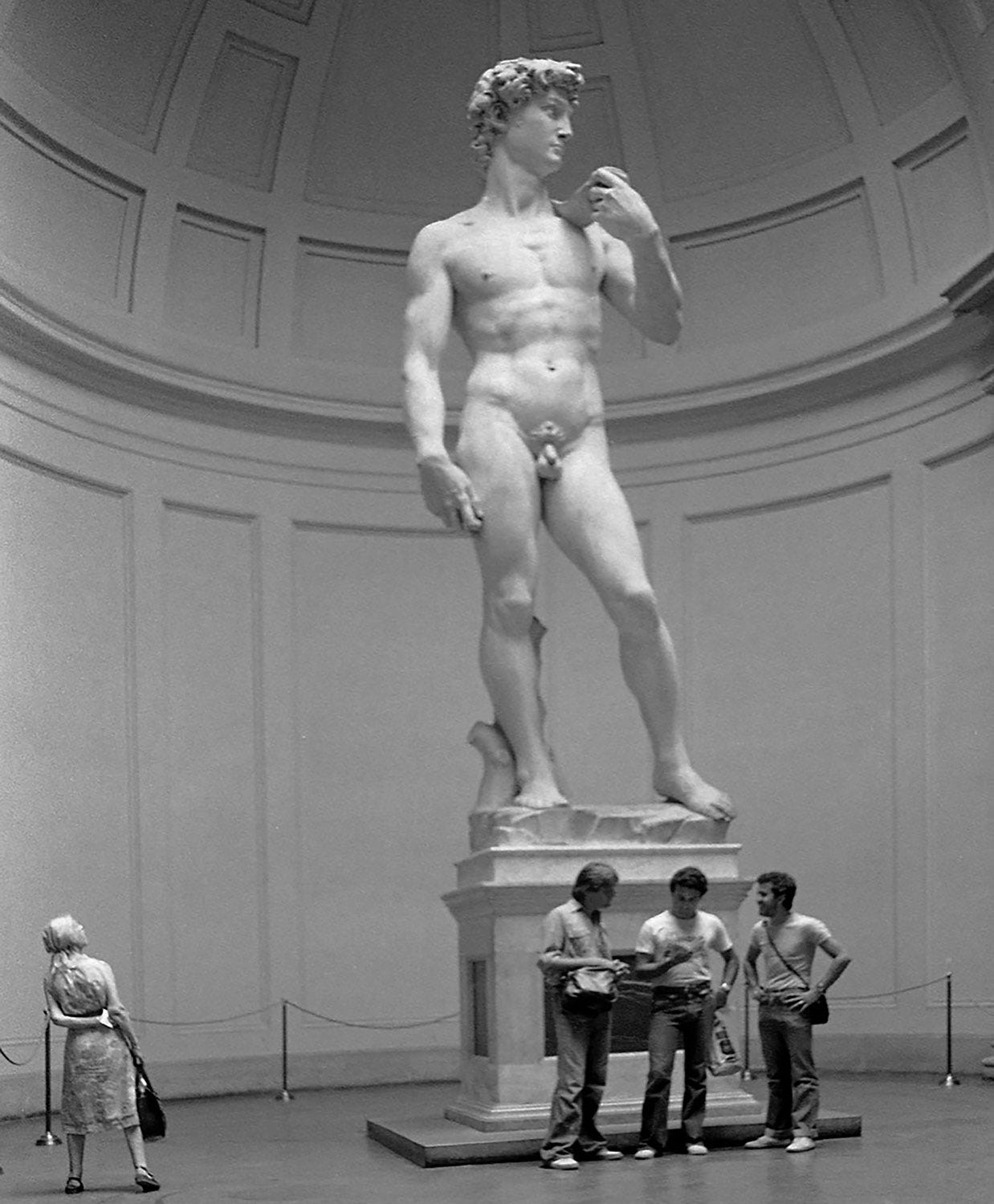

One striking way to demonstrate this is how long it took Michelangelo to carve The Giant, also known as David.

For those who have never seen David, the marble is not life-size but three times taller, at 17 feet.

Marble is so heavy that life-size marbles need to have 'three legs' —a column or tree prevents the statue from collapsing under its weight.

David weighs 5 ½ tons but has only two legs, helped by a small tree up to the knee.

And Michelangelo only needed eighteen months of work to carve The Giant.

What a way to announce that a new rooster was in town!

History Of Bad Blood Between Two Geniuses

Leonardo da Vinci was also a sculptor.

While in Milan, he aimed to create the largest bronze equestrian statue of the Renaissance, with the horse alone standing 24 feet tall.

It took Leonardo fifteen years to reach the model stage, and when French troops invaded Italy, the bronze set aside for the statue was repurposed into cannons.

The invading soldiers used Leonardo's gigantic clay horse for target practice.

When you see Leonardo's sketch below, you might weep.

Please don't, but do erase from your mind the image of Leonardo as an old wise man with a bushy beard.

His biographer gave us some clues as to the man's character:

Leonardo was so pleasing in his conversation that he won everyone's heart.

And although we might say that he owned nothing and worked very little, he always kept servants and horses; he took special pleasure in horses as he did in all other animals, which he treated with the greatest love and patience.

We also learn that he was a practical joker:

To a very strange lizard, found by the gardener of the Belvedere, he fastened some wings with a mixture of quicksilver made from scales scraped from other lizards, which quivered as it moved by crawling about.

After he had fashioned eyes, a horn, and a beard for it, he tamed the lizard and kept it in a box, and all the friends to whom he showed it fled in terror.

To return to our story, we have the older artist who worked slowly and couldn't finish his statues.

And the younger one who worked fast and delivered.

Both were ambitious geniuses. There's no biscuit for guessing what happens next.

Leonardo and Michelangelo bump into each other

Here is a rare description of an actual encounter between the two geniuses to help you imagine the scene.

Leonardo walks the streets of Florence:

A group of gentlemen were disputing over a passage of Dante. They appealed to Leonardo to explain the lines to them.

Exactly at this moment Michelangelo passed by and Leonardo replied to the questioners, "Michelangelo will explain it to you".

Michelangelo responded with anger, since it seemed to him that Leonardo was making fun of him.

"You made a design for a horse to be cast in bronze, and, unable to cast it, have in your shame abandonned it".

Saying this, he turned his heels to them and left the street. Leonardo remained at these words and blushed.

And to annoy Leonardo, Michelangelo called after him "And those Milanese idiots did believe in you?"

It is easy to imagine that Leonardo, a man of science, successfully produced electricity with the sparks of thunder generated by his eyes.

Leonardo's chance for petty revenge

The marble David was never intended to be displayed at ground level but high up, adorning the dome of Florence Cathedral.

The prominent artists of the day were tasked with finding a better spot for the masterpiece.

No one objected to seeing David's privates except for Leonardo.

He was not a prude but tried to deny his rival's masterpiece top billing.

The other pique was Leonardo's advice to artists: if you paint with overly strong muscles, you become a "wooden painter"—to be understood as Michelangelo.

The Ring: Florence's City Hall

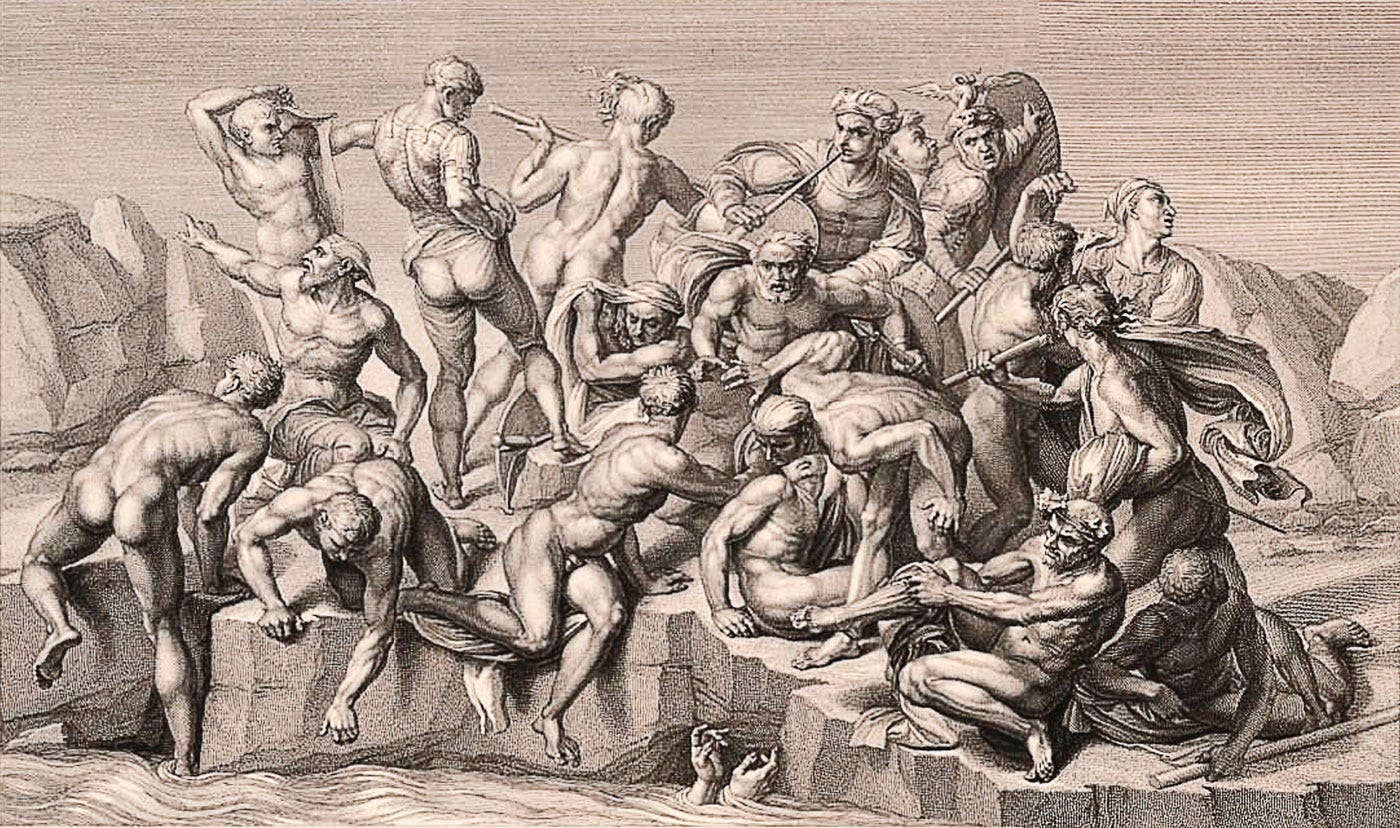

Before painting a fresco, one sketches a preparatory drawing called a cartoon that is then transferred to the wall.

It means that a cartoon is as big as a wall painting.

Michelangelo drew the Battle of Cascina, in which Florentine warriors bathing naked in the river were stealthily attacked and scuttled for action.

Leonardo sketched the Battle of Anghiari, a swirling tumult of horse riders and swords. Even the horses get in the action, biting each other.

He invented an accordion-like scaffold system that went up and down the wall.

Of course, he once more experimented with the painting mix, again trying to apply oil to a wall.

Bad omens

The only direct testimony we have from Leonardo about the Battle of Anghiari is:

On the 6th June 1505, a Friday, on the stroke of the thirteenth hour, I began to paint in the palace.

At the very moment of laying down the brush, the weather broke and the bell started to toll, calling the men to the court, and the cartoon came loose, the water spilled, and the vessel which had been used for carrying it broke.

And suddenly the weather broke and the rain poured until evening and it was as dark as night.

Leonardo went on painting the wall, and the paint dripping replaced the rain pouring.

That forced him to light braziers at the base of the wall, trying to get the paint to dry.

To no avail, as the upper section liquified and ran down the wall.

Unwittingly, Leonardo tried drip painting centuries before Jackson Pollock.

Too much sparkle and thunder in one place?

Let us hear directly from Leonardo again, where he describes the Deluge:

Oh what fearful noises were heard throughout the dark air as it was pounded by the fury of the discharged bolts of thunder and lightning that violently shot through it to strike whatever opposed their course.

Of course, that is not about the atmosphere in the Palazzo Vecchio in that room, when Leonardo and Michelangelo looked over their shoulder to see what the other was up to.

Yet it helps to imagine the tension during that titanic clash of giants.

The Fight of the Century Ended In A Draw

Michelangelo soon set off to Rome, and Leonardo once more left an unfinished masterpiece.

For a while, artists admired both cartoons. One said they were "the school of the world."

Tragically, both cartoons did not survive. The few original sketch studies that survive are fragile treasures.

Soderini, the leader of Florence who commissioned both paintings, was not too pleased with Leonardo.

He wrote:

Leonardo has not treated the Republic well.

He received a large sum of money, but has only made a start on the work entrusted to him.

In fact, he has acted like a traitor.

How much was "the large sum of money" given to Leonardo? Fifteen florins a month, which Leonardo offered to reimburse.

What do you get with 15 florins? It is not a small amount, as with 30 florins one could buy a small house in the countryside.

But in Florence, the dowry for a girl from a good family was at least 500 florins.

When compared to the wars Leonardo and Michelangelo were asked to depict, which cost up to 2 million florins, it was chicken feed.

To finance war or art, that is the question

Seen from the present, what was the better investment, military adventures, or artworks?

Is Florence renowned for its military might or as a cultural center?

And Leonardo, a traitor? Who did more for the eternal glory of Florence, the politician or the artist?

Today, the paintings exist only as secondhand memories, known from small-scale copies.

Art historians lay awake at night thinking about them, to the extent that some fantasize about Leonardo's mural somehow having survived behind its replacement.

That's where the Artistic Fight of the Century may not have ended in a tie—it never concluded.

Leonardo and Michelangelo are still influential five centuries later.

That's not just a Moment of Wonder, but a monumental one.

Notes

Anonimo Gaddiano.

Paolo Giovio, the Life of Leonardo da Vinci.

Léonard de Vinci, 2019, Musée du Louvre, Vincent Delieuvin et Louis Frank.

Vasari, the Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

Vasari's comments on Savonarola are edited for clarity, from the Life of Fra Bartolomeo :

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28420/28420-h/28420-h.htm

The Life of Michelangelo, Ascanio Condivi.

https://www.galleriaaccademiafirenze.it/en/artworks/david-michelangelo/

Photo of Firenze Palazzo Vecchio : https://www.flickr.com/photos/mustangjoe/5999631310

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Last_Supper_Leonardo_Da_Vinci_-_High_Resolution.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Da_Vinci_Last_Supper_Milan_04_2024_7035.jpg

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1868-0822-1757

https://www.albertina.at/en/exhibitions/michelangelo/

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl020110446

https://www.rct.uk/collection/912321/studies-of-a-horse

https://books.google.fr/books?hl=fr&id=roHf588GZJYC&q=rain#v=onepage&q&f=false

https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:Masters_in_art._Leonardo_da_Vinci.djvu/29

Cliff hanger!!!!