Now that Mona Lisa has been branded "the world's most disappointing masterpiece," and is about to be relegated to an underground room as if she were radioactive, it is time to redress the balance.

In this two-part series, we first discuss why a portrait became so famous.

Once done, we will go beyond the icon and discuss the person, Lisa del Giocondo, aka Mona Lisa.

A painting sold by Leonardo da Vinci to a French King

Over 500 years ago, Leonardo da Vinci sold the Mona Lisa to King Francis, his employer.

For the following 400 years, it was one of many prized artworks in the royal collection and later the Louvre museum.

It's always been a major artwork for a straightforward reason: it is a Leonardo da Vinci painting, one of only about fifteen.

Billionaires can play going to the Moon, but if they want a Leonardo, the answer will always be NO.

The last opportunity to acquire a Leonardo painting was when Christie's put Salvator Mundi for sale.

They cleverly marketed it as

The holy grail of Old Master paintings, some people call it the male Mona Lisa.

A painting that sold for $1,000 and was later branded the 'male Mona Lisa' reached $450 million.

Why is the Mona Lisa so famous?

The frenzy started in 1911 when Vincenzo Peruggia, a glazier and former employee of the Louvre, dreamt of being rich.

He worked on the protective frame for the Mona Lisa and knew the museum's service staircases.

It took him no time to pry the painting away, hide it under his worker's frock, and walk through the door.

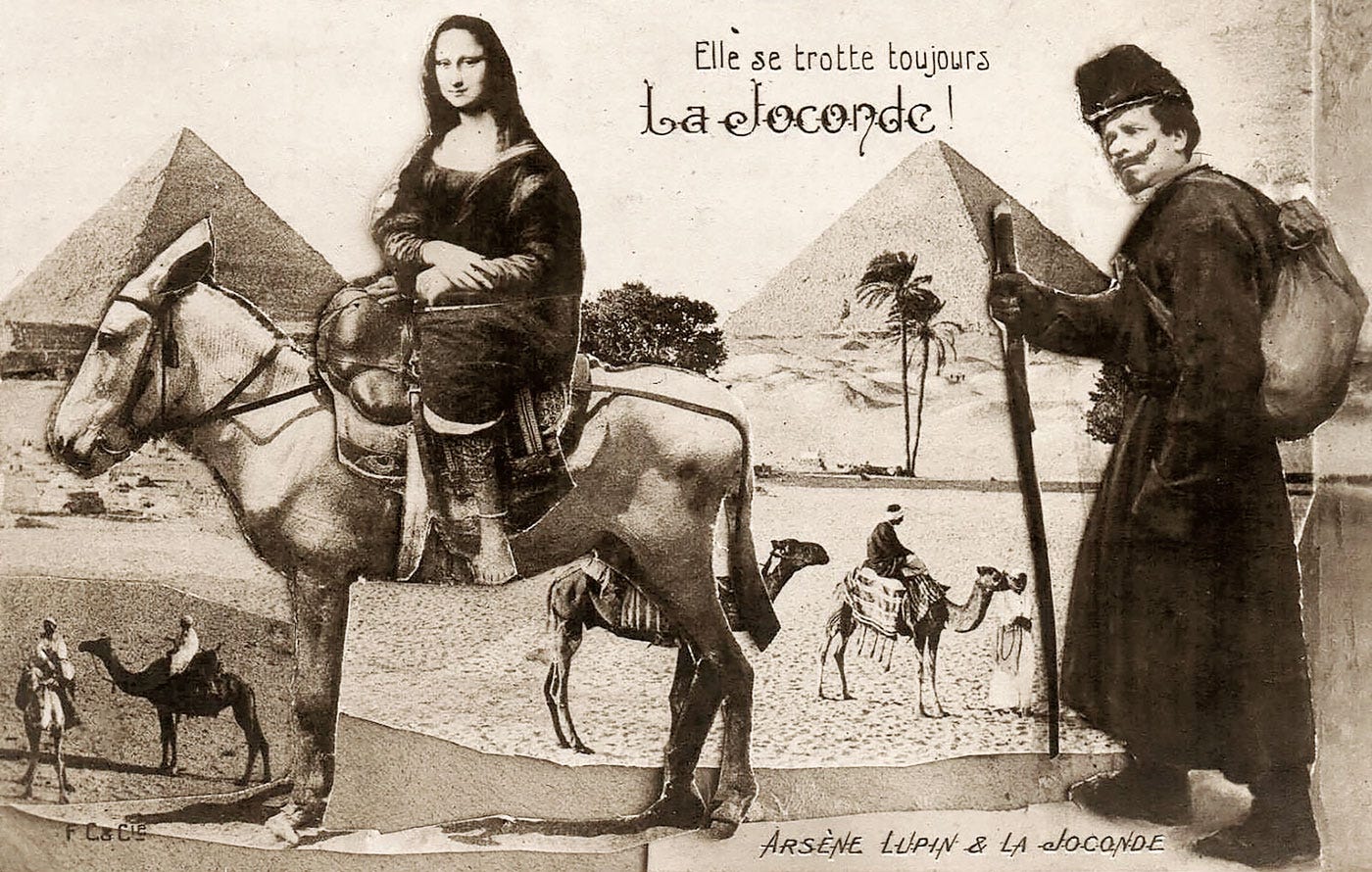

For the next two years, the media whipped up 'Where is Mona Lisa?' transforming the portrait of a lady smiling into 'the most famous painting in the world.'

Yet the painting could have been retrieved within a month or so.

Incompetent police were given the thief's name but refused to listen to experts

Let me translate for you a 1913 article about the return of the Mona Lisa:

The investigating judge was given the lead to the glazier's trail

But State Security did not deign to follow it

We are left astonished by the incapacity or negligence of the police officers in charge of the search and wonder how Peruggia escaped suspicion.

The astonishment will be even more remarkable when we learn that the correct lead was given to the investigating judge.

Jean Guiffrey—the Louvre curator—told me that the searches must be directed toward the glaziers who have recently been framing the Louvre paintings under glass.

On reflection, one of these could very well be the culprit. It is not the painters who are refecting the rooms who handle the paintings, but the glaziers.

The method by which the Mona Lisa was relieved of its frame would be enough to justify suspicions.

The truth is that the police officers showed deep disdain for the Louvre curators during the investigation.

Plain English translation:

The Louvre curators understood that only someone who knew how the frame was built could have opened it swiftly and without damage.

And be acquainted with the employees’ passageways to have escaped without being detected.

They gave the police the thief's name. His prints were already in their files and on the glass.

An inspector visited Peruggia's room but did not open the cupboard hiding the painting.

Get-rich-quick scheme fails but turns a painting into a famous icon

Contrary to what is still being repeated, Peruggia's motive had always been to get rich.

Above, you see the letter Peruggia wrote to his father four months after the theft.

Here is—for the first time—its English translation:

But I will be the instigator of this fortune that I have been seeking for a long time and that I have already dreamed about, to become a reality here precisely in Paris; when I arrived the second time, I said (here I will make my fortune, or I will die).

Peruggia went to London to try to sell the Mona Lisa and then took it to Italy to sell it.

When caught, he only had less than 2 francs, not enough to pay for his hotel room.

He changed his tune to nationalist hero.

During my work I learned that a large quantity of the paintings that were located in the Louvre had been stolen from Italy.

And that many paintings were stolen from Italy by Napoleon I.

My choice fell, with no premeditation, on the Gioconda by Leonardo da Vinci.

While Napoleon did indeed loot Italian museums, the slight detail is that Leonardo himself brought and sold the painting in France 300 years earlier.

Eeny, meeny, miny, moe; catch a Leonardo

It is quite staggering to realize that he picked up Mona Lisa 'with no premeditation.'

The choice was practical: it did fit under his worker's smock.

Had he walked two meters more on the right, the very same masterpiece that few visitors even glance at today would be behind bulletproof glass, about to be moved to a secure room.

Peruggia's playing the nationalist's fiddle worked a charm; he received a light verdict and spent only seven months in jail.

The Mona Lisa was exhibited in Italy before returning to Paris, and tens of thousands of visitors visited it daily.

Before the theft, most visitors walked past her, but after the robbery, she was behind lines and crowds.

One man's dreams of fortune cost him prison time without even one centime of profit. There was no book deal, nothing for Peruggia.

Did he consider whether it was worth it while in prison?

While his only reward was the free bread and soup, he condemned the Mona Lisa to an eternal sentence.

That of fame.

A portrait is nothing but a portrait

The first reason many find the Mona Lisa 'overrated' is that it is 'small.’ Yet it is nothing more than one should expect: a portrait.

A lifesize painting of a smiling lady sitting on a chair.

I will always advocate that a painting in real life is vastly superior to its photographic reproduction, but I must concede that there is one exception: the Mona Lisa.

Click on the link to the image below to access a High-Definition photograph.

This will allow you to get closer to the Mona Lisa than pressing your nose to the bulletproof glass.

Like Marilyn Monroe, we see one person with two facets: the famous and talented sides.

If Marilyn were still with us, one could see a celebrity behind a wall of photographers, not unlike how one sees the Mona Lisa in the Louvre.

Or be fortunate to listen to Marilyn talk candidly about her passions at a conference or in a documentary, walking us through her library and music collection.

That would allow us to go beyond the icon and see that celebrity hides an intelligent and talented person.

But Marilyn's fame consumed her, and within moments of her death, the media voyeurism denied her the respect due to the dead.

The same thing was attempted on Lisa del Giocondo 500 years after she posed for Leonardo.

Desecrating the dead for 15 minutes of fame

The purpose of the dig was to reconstruct Mona Lisa's face once her skull was found to 'prove' whether she was Lisa del Giocondo.

For fifteen minutes of fame, someone had no qualms in perturbing Florentine nuns' eternal rest, hoping to 'reveal' a new truth about the Mona Lisa.

Ask yourself: how many tombs are opened to prove that the person depicted in a painting is that person?

Make anything up about the Mona Lisa, and the world press will breathlessly repeat the nonsense.

Want to make a political point? Thow acid, rocks, paint, tart or soup at it. It is no wonder that a painting has to be protected from its fame by bulletproof glass.

Like a self-eating monster, its celebrity keeps growing exponentially.

That is why the gulf between the weight of expectations and the reality that it is nothing more than the portrait of a lady means she will continue to be voted the "most disappointing masterpiece."

The Mona Lisa is inside a whirlpool; the more famous she becomes, the more underwhelming she will be.

It is like waiting for hours for five seconds near Marilyn. A fleeting glance at an icon, missing out on Norma Jean.

Hiding behind the Most Famous Painting In The World™ is a person called Lisa del Giocondo.

Who was she?

The answer comes in Part II, The Woman Behind Bulletproof Glass.

Notes

https://artjourneyparis.com/blog/mona-lisa-story-behind-fame.html

https://collections.louvre.fr/en/ark:/53355/cl010062370

https://archiviodistatofirenze.cultura.gov.it/asfi/mostre/vincenzo-peruggia-3

La piste du miroitier avait été signalée au juge instructeur, l’Intransigeant, 18 Décembre 1913. Translated and edited for clarity.

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k786941j.item#

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marilyn_Monroe_in_1952.jpg

Mona Lisa: The People and the Painting, by Martin Kemp and Giuseppe Pallanti.

The Hunt for Mona Lisa's Bones Is A Publicity Stunt, Not Science