Rodin and Camille Claudel meet and influence each other.

The story of Camille Claudel's emergence as a sculptor.

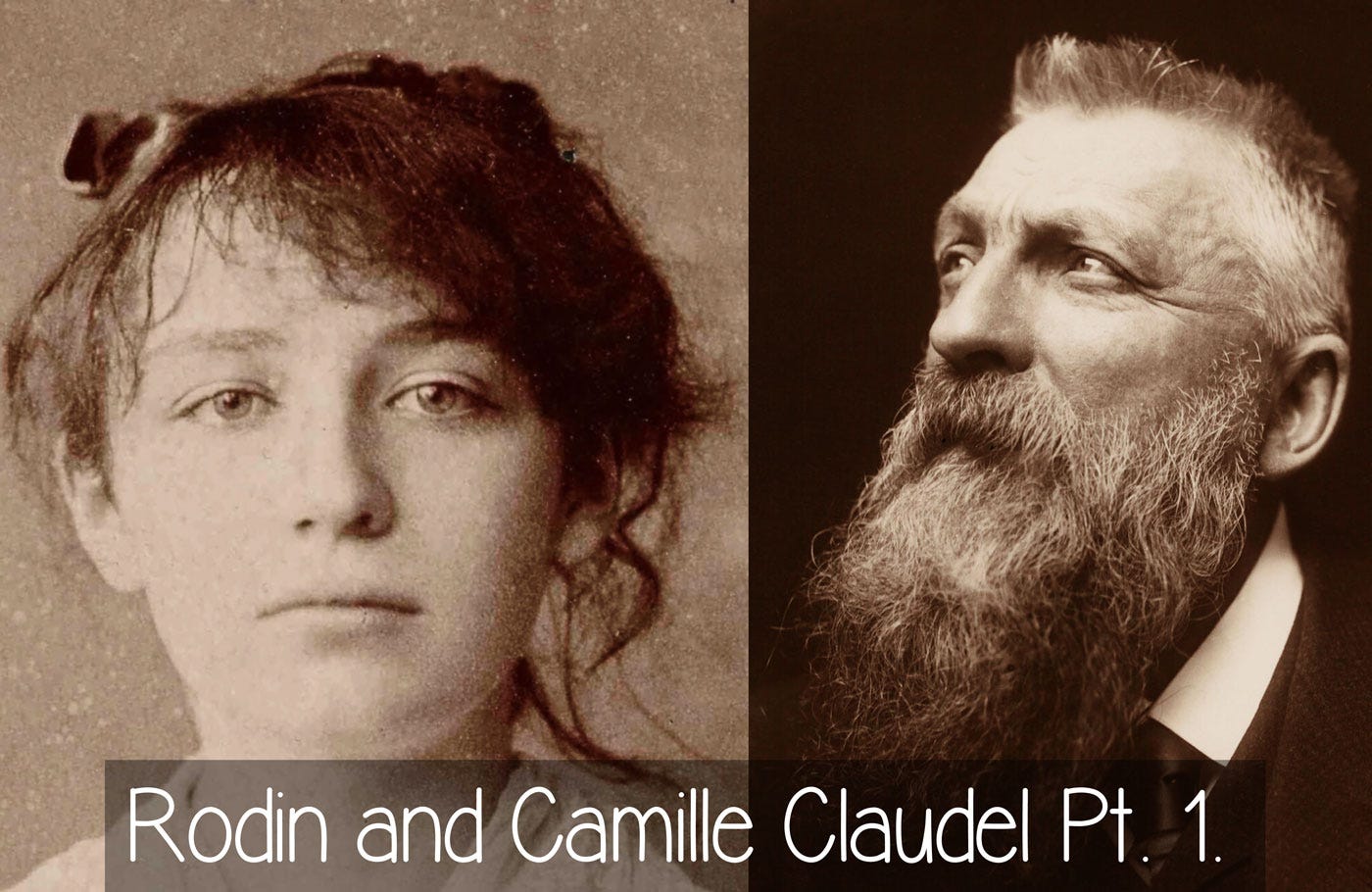

Dear reader, did you know Rodin had to wait twenty years to become an artist? After earning first prize at the small art school, he assumed that entering the Beaux Arts School would be easy.

Instead, they smashed the door in his face, not once, not twice, but three times! In despair, he left Paris and made a living as a craftsman in Belgium, only starting a career as an artist at age 40.

If it was that hard for one of history's greatest sculptors to make it, imagine what it was for a woman. It would have been pointless to even dream of entering the Beaux Arts School. The only way a woman could be in class at the Beaux Arts School was as a model, not as a student.

This is the tale of two major sculptors destined to meet and influence each other.

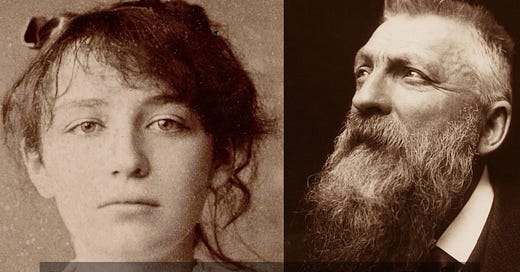

Camille Claudel: birth of a sculptor

Our story starts in 1864. While a 24-year-old sculptor struggles in Paris, a baby girl is born into a bourgeois, provincial family.

The family's summer home included a kiln and a clay pit. Sculpting clay became a "violent passion" for the little girl from age seven. She convinced everyone to bring her clay, to pose for her, or both.

The contrasting characters of her parents would shape her life and career. Her mother was a rigid, unimaginative woman who never even kissed her children. But her father was a conservative yet progressive, well-read man who was happy to encourage his children's creativity.

Without having taken any lessons, she was good enough to create a statuette at age thirteen that attracted the attention of a Beaux-Arts graduate.

He readily agreed to give the budding artist sculpture lessons. The family's private tutor also recognized the young girl's talents, and both teacher and sculptor were happy to help Camille develop her passion for sculpture.

Studying the arts as a woman in the 1880s

After much begging, Camille persuaded her father to move the family to Paris so she could study to become a sculptor. That was an incredibly generous decision from him, as he let his wife and children move to Paris and stayed behind to work and be able to afford the move.

Aside from the financial investment, Camille's father risked his standing in the respectable bourgeois society by letting his daughter become an artist. What would people say? You see, dear reader, the issue was 'decency'.

'Decency' prevented women from looking at nudes, and the basis of academic teaching was the nude. That meant that women were, at best, railroaded toward decorative arts but, in practice, denied access to fine art.

Pondering the number of broken dreams caused by 'decency' reminded me that my grandmother was forbidden from becoming a nurse as that implied she might see naked men...

How many women were prevented from improving the world by this misplaced fear of the human form?

In the story "Women Artists Painting Smiling Faces," we discussed how rare it was for a woman to succeed as an artist. That was the context to understand how fortunate Camille was to have a father ready to encourage her dreams.

Camille, recognized as an artist before she met Rodin

Independent, private art academies sprouted as an answer to the conservative Beaux Arts School. Camille enrolled in one of these, where students, men and women, learned sculpture in front of nude models.

Camille shared a studio with other young women, as, once again, it was unthinkable for a young lady from a good family to be alone with men. One of them would end up becoming a lifelong friend.

Boucher, the sculptor who recognized young Camille's talents, paid frequent visits. One day, he brought a good friend of his, the director of the Beaux Arts School. Looking at Camille's work, suitably impressed, he said to her:

You took lessons from Rodin !

But Camille did not even know who Rodin was. That remark shows that Camille was talented before meeting Rodin and that these two were destined to meet.

Tradition dictates that masters freely offered advice to younger artists, which is why Boucher helped Camille. When he had to leave Paris, he proposed to Auguste Rodin that he replace him by regularly visiting studios to offer advice to students.

Rodin, the master

Master is not a word of praise but a title describing an artist who runs a studio and employs assistants. Rodin had to wait until he was 40 to be a master.

Only when he received a commission to create a masterpiece, the Gates of Hell—which will be a future story—did Rodin's life change from hoping to get work to employing others.

Rodin, the master, now 42 years old, was in a position to teach younger artists. And he needed assistants to help him with the Gates of Hell.

Master and assistant influence each other

Rodin visited Camille and her friends' studio to give them free advice. Eventually, the Gates of Hell required so much work that he needed assistants. Upon recognizing Camille and her English friend Jesse Lipscomb's talents, he offered them both jobs in his studio.

Remember, dear reader, that women could not enter the Beaux Arts School and were widely considered unable to work like men. In their corseted garments, the poor little dears could not carry heavy materials or work hard in a dirty environment.

Yet Rodin needed these two ladies' skills, so he employed them as assistants, the same as their male colleagues.

By definition, an assistant learns from the master. No one will deny that Rodin influenced Camille, but realizing that the influence went both ways is essential.

While the Beaux Arts director assumed that Camille had taken lessons from Rodin before meeting him, her biographer insists that:

Right away, Rodin recognized Mademoiselle Camille Claudel's prodigious gifts.

Right away, he realized that she had, in her own nature, an admirable and incomparable artistic temperament.

He became not a teacher but rather a brother of the young artist who later became his loyal and intelligent young associate.

If you think that Camille's biographer exaggerated, use your own two eyes below:

Now that we have seen that Camille was not one of the slavish followers and could influence him, we need to discuss his influence on her.

Rodin had dozens of assistants. He was the Michelangelo of the 1800s, so he influenced everyone, starting with those who worked for him.

Before Rodin, sculpture in France was so frozen that, in the words of Camille's biographer, the studios of other sculptors looked like they had cadavers lined on their walls.

Rodin's studio was filled with life itself.

"I showed her where to find gold, but the gold she finds belongs to her"

We will later discuss Auguste's love story with Camille, but first, we need to understand how he respected her as an artist.

In the "Jimi Hendrix Effect" story, I illustrated that what makes an artist important is their effect on other artists. Esteem from one artist to another is the highest form of praise. For Rodin, Camille was more than an assistant.

In painting and sculpture, the eyes, face, and hands are the easy telltale difference between master and assistant. Rodin trusted Camille to model hands and feet for his statues, and several of Camille's works were long considered Rodin’s.

The relationship between the employer and the assistant went as follows:

It would be closer to the truth to say that Mademoiselle Camille Claudel became his perceptive and sagacious collaborator.

Rodin, who recognized the future great artist from the onset, only considered her as such.

Without a doubt, he shares all he can of his great experience with her. But he consults her about everything.

He deliberates each decision with her, and it is only after they are in agreement that he definitely proceeds.

Camille even carved some of Rodin's marbles. Most people are surprised to discover that Rodin employed others to carve his marble statues.

At a time when women were forbidden entry to the Beaux Arts School, Rodin did not look down on Camille but saw her as an equal.

Camille Claudel, a major artist at the risk of oblivion

Camille's brother wrote that:

What makes my sister's work unique is that her entire work is the story of her life.

In the second part of the story, we will discover her life after the intense love story between Rodin and Camille; tragedy after tragedy befell her.

Her mother and brother sent her, against her will, to the asylum. She died in 1943, after thirty years—like a prison sentence—without being able to create.

From the asylum, Camille wrote that:

I have fallen into an abyss. I live in a world so curious, so strange.

Of the dream that was my life, this is the nightmare.

The worst outcome for an artist's career is to fall into the abyss of oblivion. In Camille's case, to be considered nothing more than Rodin's follower, the equivalent of being a tribute band, never as good as the original.

It bears being repeated, but, like Rembrandt or Michelangelo before him, Rodin sucked up all the creative oxygen. From being thrice rejected, he became a living monument.

Alone, he renewed sculpture as much as Manet, Monet, and Renoir combined did to painting.

A woman artist who destroyed her work and ended up in a provincial asylum may have ended up, at best, relegated to the status of footnote in art history, and, at worst, completely forgotten.

Fortunately, that did not happen, and this story is meant to provide you, dear reader, with a Moment of Wonder, helping you realize that Camille Claudel was more than Rodin's lover and assistant.

Next, we will wonder at their love story and how her legacy survived.

Sources

Mathias Morhardt, Mademoiselle Camille Claudel, Mercure de France, 1898.

Odile Ayral-Clause, Camille Claudel : A Life.