When a Van Gogh was used as a chicken coop door

True story of a masterpiece survival

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, the myth about van Gogh isn't exactly true.

He DID exhibit, and he DID get recognition from fellow artists in his lifetime. That will be a future article.

But it remains that his art was so shockingly modern that most people did not understand it.

Let us enter the time machine and land in the 1880s.

It's only been ten years since the birth of that horrible thing called Impressionism.

The word is an insult a journalist threw at a talentless bunch of young painters.

The press called Impressionist paintings "daubs splattered by monkeys playing with colors" or "a war against beauty."

It is no wonder that Monet—who waited about 25 years for financial success—jumped into the river in a suicide attempt.

Let's have a look at what proper art looked like:

Photography is fifty years old, and the Eiffel Tower recently opened.

It is the train and telegraph age and the dawn of Chicago and New York skyscrapers.

Yet, 'real art' should still be a skillful copy of reality and be about 'serious' stories, such as religion or great figures of the past.

Unsurprisingly, most people thought that blurry images of railway stations were not art.

Now, we arrive in provincial France, in Arles, Provence. A stranger scares off some locals, who want him out of the city.

The newcomer is an artist who creates hazy, colorful images that seem, to most people, badly painted.

He could leave his artwork outside during lunch, and no locals would steal the painting.

He's a bit weird. Yes, our friend Vincent van Gogh.

Whether his talent owed to his 'crazy' side will be for another story.

It still must be said that one night, Vincent walked toward Gauguin with a razor blade in hand.

Vincent ran away, cut off his ear, and collapsed. The following morning, he was brought to the hospital.

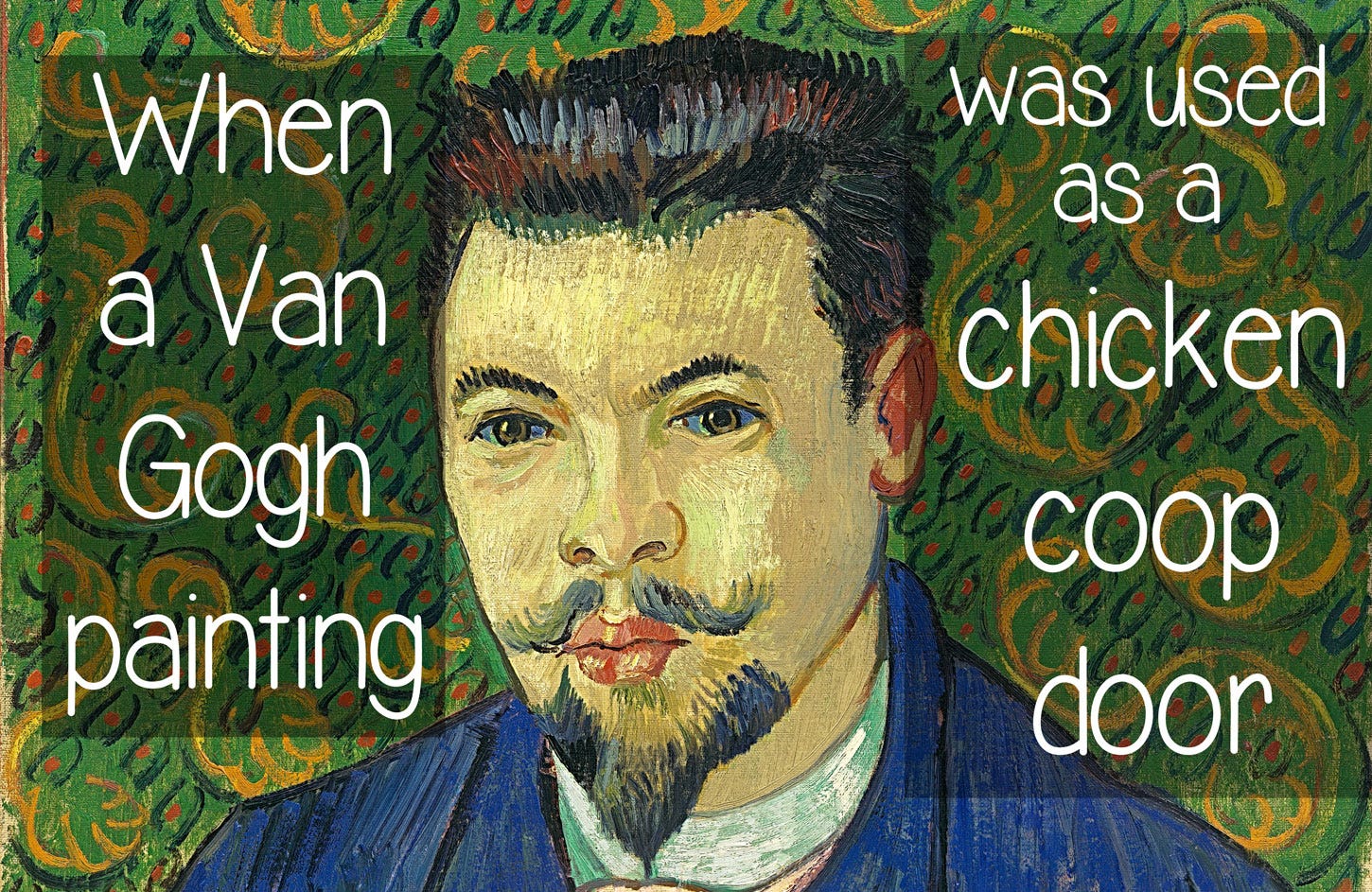

Dr. Rey, Another Kind Person In Vincent's Life

His luck was to have been attended by a young doctor, Félix Rey.

Treating a man who mutilated himself would be plenty of reason to dismiss the person as 'insane.'

This is not at all what happened.

First of all, young Docteur Rey was familiar with epilepsy and believed that Vincent had suffered from it.

That was not dismissing Vincent as 'insane,' but seeing him as a person suffering from a medical condition.

Second, Docteur Rey was not just kind-hearted; he was curious.

One day, those two discuss painting for over an hour. Vincent relates their conversation:

"He had already told me before this morning that he likes painting, although he knows little about it, and that he would like to learn.

I told him that he should become an art lover".

Vincent talks of Rey as "a really good fellow" who allows him to paint in the hospital courtyard and gladly accepts to pose for him.

He then presented the portrait as a gift to his doctor, a man living in provincial France who readily accepted that he knew little about painting.

Looking at his yellow face and the riot of colored brushstrokes, the doctor found it difficult to accept this was 'art.'

Not long after, Vincent tried to give a second painting to his friend. This is what happened:

Dr. Rey turned it down and suggested that Vincent try to offer the self-portrait to another doctor, who responded:

“What the hell should I do with such rubbish”.

The French word used was cochonnerie, literally, "pig-like," as if done by a pig.

And Vincent was not trying to sell a painting; he was giving it away.

Using a Vincent van Gogh as a chicken coop door

That's the context needed to understand what comes next.

Dr. Rey gave his portrait to his mother, who was far less open-minded than her son.

By good fortune, the painting was the size of a hole in her chicken coop.

So, she used it to plug the gap. The other good fortune is that the chickens also dismissed Vincent's art as cochonnerie and did not peck at the canvas.

Had they found Vincent's art deliciously colored, the painting would be gone.

A group of lucky chickens occupied their days in that coop beak to nose with Dr. Rey for twelve years.

By then, the doctor treated a patient who happened to be an artist, and was happy to tell him he knew Vincent.

The man wanted to know if he still had paintings as he would like to purchase them.

Dr. Rey went to his mother and asked about the chicken coop door. Except for one hole, it survived.

It was cleaned up and brought to the attic, along with five more canvases that Rey owned.

Dr. Rey discussed the plan to sell them with his parents, only to be told he was greedy. How can you ask 50 francs for daubs that are not even worth 50 cents?

The portrait sold for 150 francs, and the other five canvases a combined 200 francs.

My friend Van Gogh, a remarkable genius

In 1930, near retirement, Dr. Rey received a demand about the cut ear incident. He sketched the injury with the following letter:

While most journalists focus on the ear—whether it was entirely cut off—we will concentrate on what Dr Rey wrote:

"I’m happy to be able to give you the information you have requested concerning my unfortunate friend Van Gogh.

I sincerely hope that you won’t fail to glorify the genius of this remarkable painter, as he deserves."

Like Joseph Roulin, as we already discussed, Félix Rey, for being kind to this remarkable genius, is now eternal.

Not that bad for a cochonnerie only good for chickens!

And a fair reward for being a good doctor and a nice person, don't you think?

There is a lot to say about Vincent van Gogh, so this might become a Van Gogh series.

Sources

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4539511/

https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let735/letter.html

https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let776/letter.html

https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let760/letter.html

https://vangoghletters.org/vg/documentation.html#id29December1888-1