In the story Watteau, or not Watteau, I explained that out of 35,000 artworks on display in the Louvre museum, there are, at a guess, about 12 smiles.

That made me think, so I walked through most of the Louvre, searching for smiling faces.

It's quite a big haystack to explore in search of tiny needles.

The smile ratio works out at about 0,005% if we count only statues and paintings.

Today, we discuss a rare theme, smiles in art.

Why were there no smiles in ancient art?

The past is a foreign land. Before photography, the reason for making images was not at all 'art' as we understand it today, something one does for pleasure.

Art was propaganda.

Yes, propaganda, per the word's original meaning: to propagate—spread—an ideology.

Paintings or statues were generally meant to educate the public about the gods, Kings, or Emperors.

Hence, portraits were that of political or religious leaders.

They were not intended to make you think you could have a beer with them but to know your place.

The portrait above is that of an Emperor with armor, holding a baton of command.

If the way he looks at you is not enough, he holds a command baton, a reminder that he can club you on the head with it.

Rotten smiles

Another reason for the absence of smiles is poor dentistry.

If you wonder why you’ve never seen portraits of Louis XIV smiling, consider the terrifying absence of hygiene in his day.

Louis, in his late 40s, had barely any teeth left.

Imagine Versailles in its prime: a King who had the best doctors of the time, yet his medical history is the stuff of nightmares.

In other words, from peasant to royal, very few people had a nice smile to offer.

The people portrayed look at eternity

The other reason, which is difficult to comprehend in an age when billions of images are created daily, was that having one's portrait taken was exceptional.

The rarity of portraiture can be explained by the cost of commissioning a bronze, marble, or painted image.

Hence, one must contemplate that most of humanity never had their portraits taken.

Most of our ancestors had to see faces intensely and memorize them.

There was no portrait to reminisce about what a departed parent or an absent spouse looked like.

When a King sat for a portrait, it was to talk to the present—this is whom you pay taxes to—and send a message to History.

As Churchill supposedly said

History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.

With the advent of photography, in the 1800s, when more people could have their portraits taken, the tradition inherited from painting continued.

For 'regular' fortunate portrait sitters, it was to appear in the future.

To address their offspring, and, hopefully, be like a message in a bottle, sailing on the ocean toward eternity.

Entering a conversation with our ancestors

If I am allowed to share a personal story, I own photographs of my grandmother's grandparents, people born in the 1860s.

Above is my great-great-grandmother, born in 1864. She was a music prodigy who first played a piano concert at age six.

This signed photo is one way for me to meet her. Although I am a useless musician, I feel her artistic sensibility flowing through my veins.

A portrait allows for a conversation between worlds. This one allows me to connect with a person born 160 years ago.

Anyone fortunate enough to have pictures of ancestors can connect with long-lost parents.

What we see are stiff poses and serious faces, yet our ancestors had a sense of humor and laughed.

It just so happens that smiling was almost never shown in portraiture.

Today, we focus on the 0,005% times when people smiled in artworks.

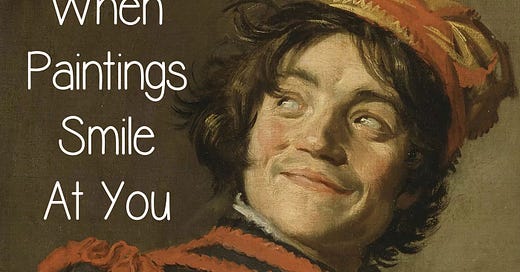

Frans Hals, A buffoon playing a lute

We set the bar quite high, starting with Frans Hals.

Two paintings, both shortlisted for my "100 Masterpieces of the Louvre" project.

Sip some coffee, then guess how old this portrait of a man playing music is.

What do you think? In the 1880s, something that another Dutch painter, Vincent van Gogh, might have painted?

No, we are in the 1620s.

If you are not familiar with Frans Hals, you have heard about Rembrandt, haven't you?

Let's make your life easier and put Hals on a pedestal not far from Rembrandt.

Even when a photo flattens images, the brushwork is visible and fast.

It feels like Hals asked the sitter to smile, and before the guy's facial muscles gave up, the painting was finished.

This is still a typical 'genre painting', showing you what not to do, which will be explained further with this series on smiles.

In any case, this painting is shortlisted due to its modernity and Hals's ability to capture a fleeting expression of cheekiness.

But there is a second one a few meters away.

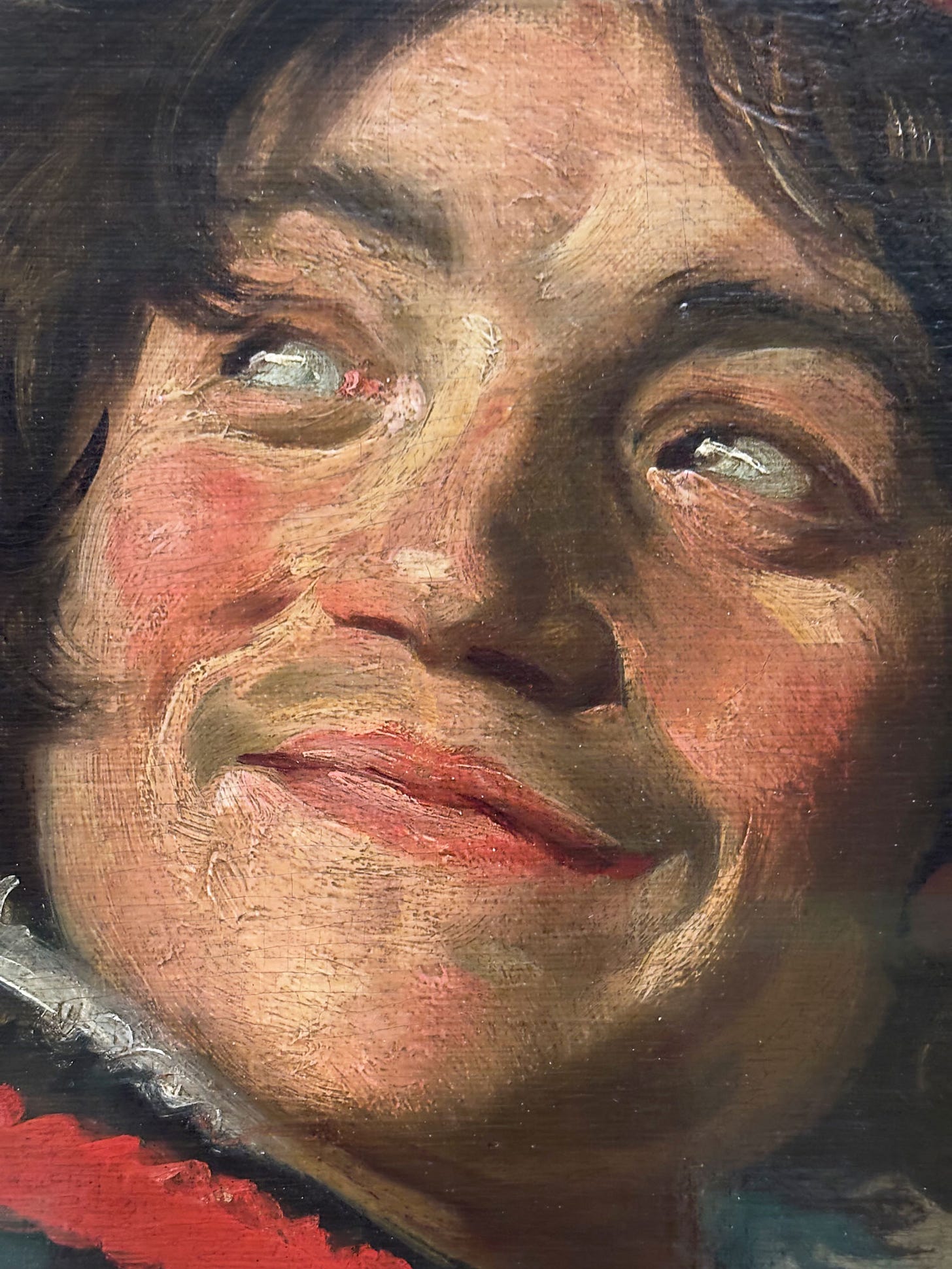

Frans Hals, the bohemian or Gipsy Girl

When you walk the corridors of any museum, you have serious gazes looking at you.

The intensity of a King’s stare is to remind you who’s boss. A religious figure wants you to elevate your mind to higher things.

They don't want your input; these faces are not conversation starters but one-way exchanges.

The marvelous painting above does need you.

Of course, it is a moralistic tale, but to understand the story, you need to stand in front of the painting.

She wants you.

You are a naive man, she is the fortune teller you met in that place of ill repute—the tavern—and she holds your hand.

She tells you what you want to hear: “yes, I can see in the future that you will be prosperous and meet a beautiful lady.”

To ensure your mind will not veer off from that lovely daydream, her cleavage keeps you focused.

Pay attention, though. That is a crafty, sardonic smirk.

Her eyes are in the opposite direction as her grin. She is not looking at you in the eye, a telltale sign that she is lying.

Her left hand is in your pocket—hold that thought, not for your benefit!

She was looking for your wallet, and she found it. She smiles, bemused at how easy you've been to mark!

Which was indeed a Moment of Wonder, but for her!

Bonus images

Taken by myself in the Louvre, with more smiles to come.

Poor lighting and often glass covers make it difficult to take good pictures, but one is trying.

Notes

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gnrn/hd_gnrn.htm

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437869

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010060266

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010064339

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hals/hd_hals.htm

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gnrn/hd_gnrn.htm