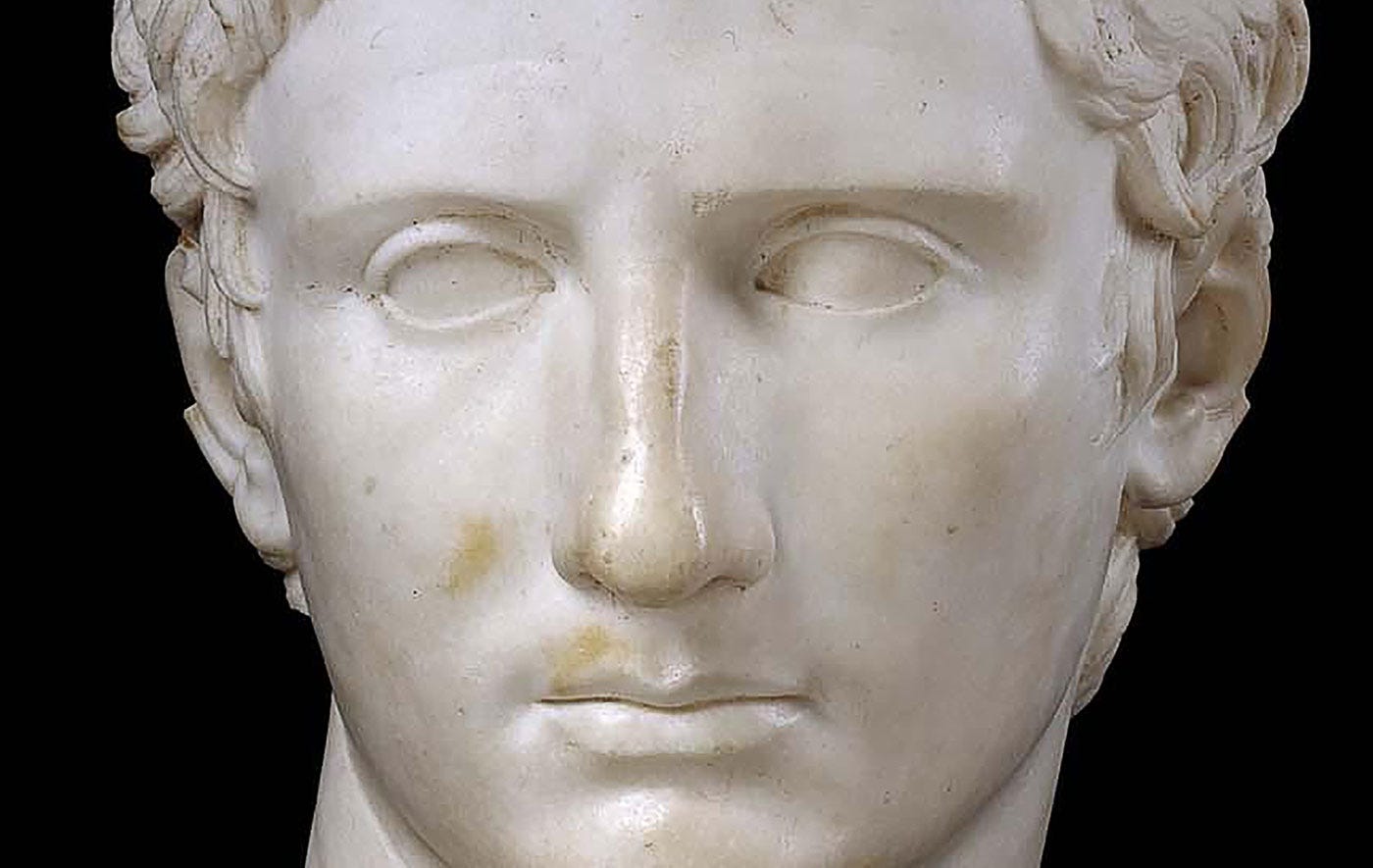

Although our two smiling statues are white, please erase from your mind that the past was a sea of milk.

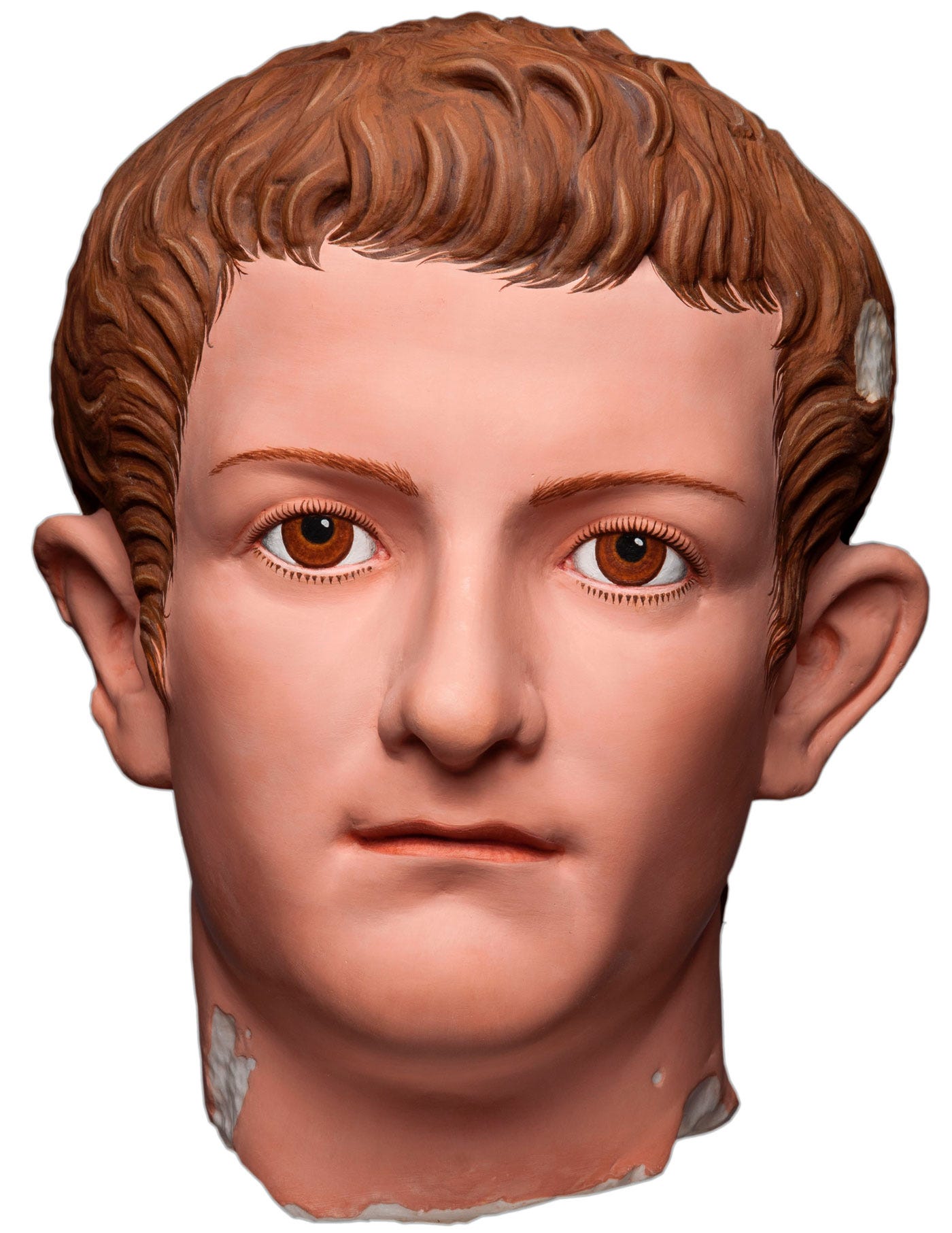

The right statue is made of plaster, while the left is made of rare ancient Greek marble. It is still colored—the eyes, beard, and hair.

A quick reminder that ancient statues were not pale zombies

Don't laugh or run away. This is what ancient statues did look like.

Have you ever wondered why most ancient marble statues you have seen appear as zombies, needing a fresh supply of blood to get a better complexion?

Did you notice they have a blank stare and empty eye sockets?

Humans and gods had eyes, but the color of the painted eyes has disappeared with time.

By contrast, the reconstitution of what Emperor Caligula's statue looked like is a reminder that marble portraits were painted.

That provides a little context for appreciating our first smiling statue, affectionately known as the Rampin horseman.

The Rampin horseman

Explaining how rare reasonably intact ancient Greek marbles are is for another article.

The backstory is that this statue was displayed at the Acropolis of Athens about 100 years before the Parthenon was even built.

It means this marble head is around 2,550 years old.

Note that its eyes are still painted and the beard and hair still have reddish color traces.

The head was discovered among a heap of broken fragments, due to the Persian sack of Athens.

Rampin is the name of the person who purchased it and eventually gave it to the Louvre—merci!

I will not bore you with minute details about the Archaic, Severe, and Classical styles.

Just know that when our horseman was carved, this gentle smile was the norm. And that does not change the reason we admire it today.

It is, in fact, on the shortlist of the "100 Masterpieces of the Louvre."

Who was the horseman?

We do not know. But the educated guess—both the cost of marble and owning a horse— was that he was a member of the aristocracy.

Or maybe an athlete celebrating a competition.

A headless horseman was discovered among the heap of broken statues and is in the Acropolis Museum today.

It took sixty years for someone to notice that Rampin's head and the headless rider fit perfectly.

He seems relaxed and quite content, having won a horse race.

We can imagine him riding along, soaking in the public's applause.

What you may not see is that he rides naked. It's unlikely that the competition involved trotting, as our horseman would not smile like that.

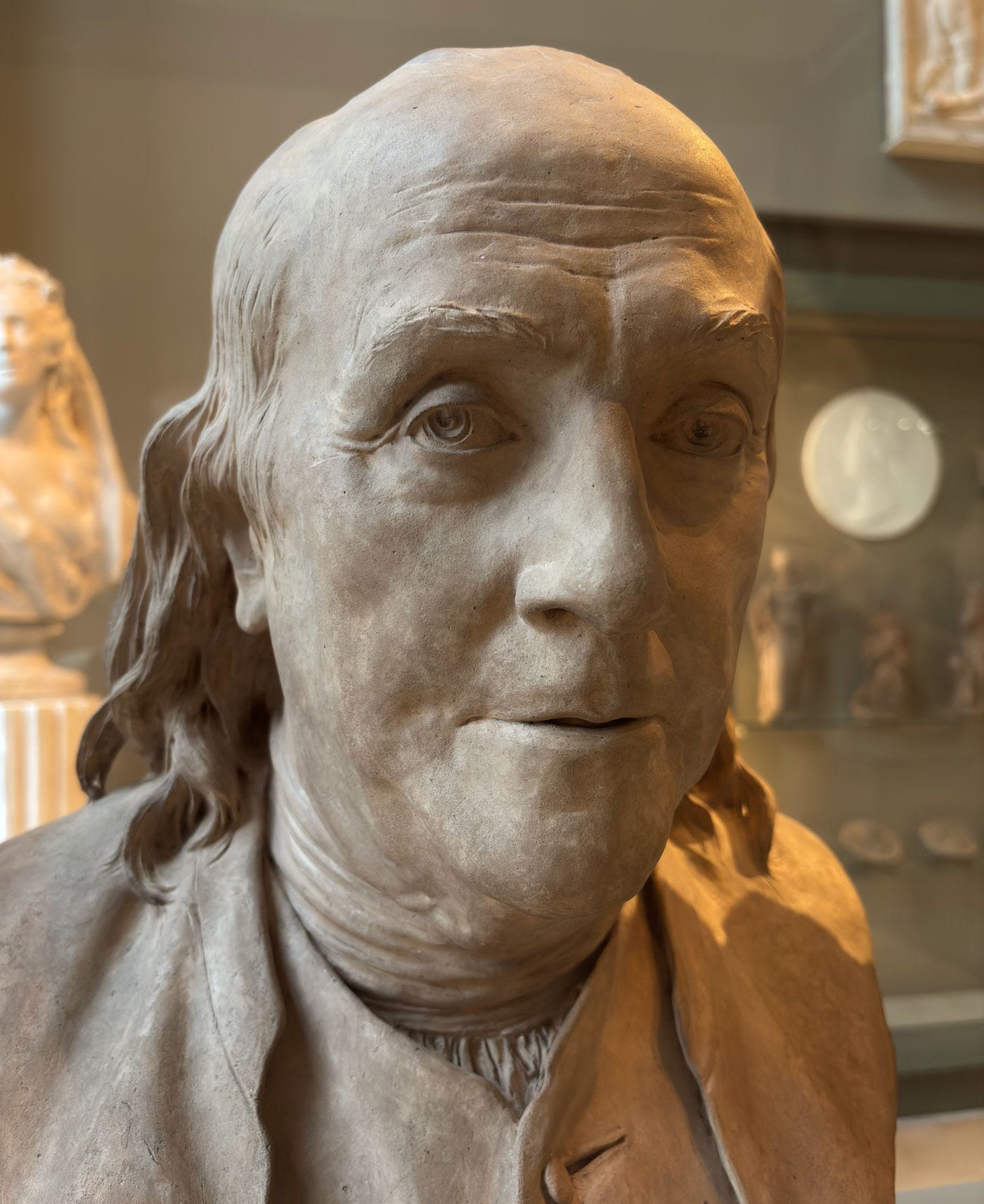

Jean-Antoine Houdon, Madame Houdon

What a pity that almost no one looks at the corner of the Louvre where Houdon's statues of his family are displayed.

If you have never heard of Houdon, do not worry; you will soon remember.

Broken record alert: most art of the past was propaganda commissioned by political and religious leaders.

Houdon underwent formal training and a career as an official sculptor—see the portrait of Louis XVI below.

But the statues we discuss here were not commissioned by a powerful figure; he made them for himself, to be precise, out of love.

This plaster is the original that Houdon exhibited at the official Salon under the title 'Portrait of a young lady.’

Houdon did not mention that the young lady was Marie-Ange-Cécile, soon to be Madame Houdon.

Do you feel the love and tenderness in the eyes and smile?

And look at the children:

And with whom did Marie-Ange-Cécile share the exhibition stage at the official Salon of 1787?

Let's read the labels. Maybe you know the names:

- M. le Marquis de la Fayette.

- General Washington, made by the author at the General's lands in Virginia.

Madame Houdon, today, smiles at this man two meters in front of her:

Can you guess who that is? Marie Antoinette called him l’ambassadeur électrique.

The electric ambassador, also known as Benjamin Franklin.

You did not see that one coming, did you? Yes, George Washington and Benjamin Franklin are in the Louvre.

More original masterpieces by Houdon are in the Virginia Capitol, Mount Vernon, the Smithsonian, and as copies elsewhere.

At least as statues, Madame Houdon rubbed shoulders with George Washington, Lafayette, and Benjamin Franklin, quite the company.

I trust that you will remember the name Houdon now.

That was a Moment of Wonder for today.

Notes

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010276879

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010093758

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010095592

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010094299

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010092919

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010092918

https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/jean-antoine-houdon