Wondering at Leonardo da Vinci's drawings

Making sense of the rarity of Leonardo's notebooks, with practical advice on admiring these rare and fragile masterpieces.

Dear reader, we did some detective work to find the only portrait of Leonardo da Vinci drawn from life. Discovered his unsung masterpiece, the Scapigliatta. Here, we wonder at another facet of Leonardo's genius: his engineering and medical notebooks.

We will first discover the vast difference between the myth and the reality. Then, considering how rare and fragile the drawings are, explain how you can wonder at them from home better than in real life.

What really happened to Leonardo's drawings

Let us first try to imagine how many notebooks Leonardo da Vinci filled. In his 50s, his inventory stated:

25 small books, 2 major books, 16 larger books, 6 books on parchment, 1 book with green suede cover.

He also wrote about

The hundred and twenty books which I have composed.

Even if these were chapters more than books, it is a certainty that Leonardo wrote and illustrated many books. We have one witness to this, in the last years of his life, who reported:

This gentleman has written a treatise on anatomy, showing by illustrations the members, muscles, nerves, veins, joints, intestines, and whatever else is to discuss in the bodies of men and women, in a way that has never been done by anyone else.

All this we have seen with our own eyes, and he said that he had dissected more than thirty bodies, both of men and women of all ages.

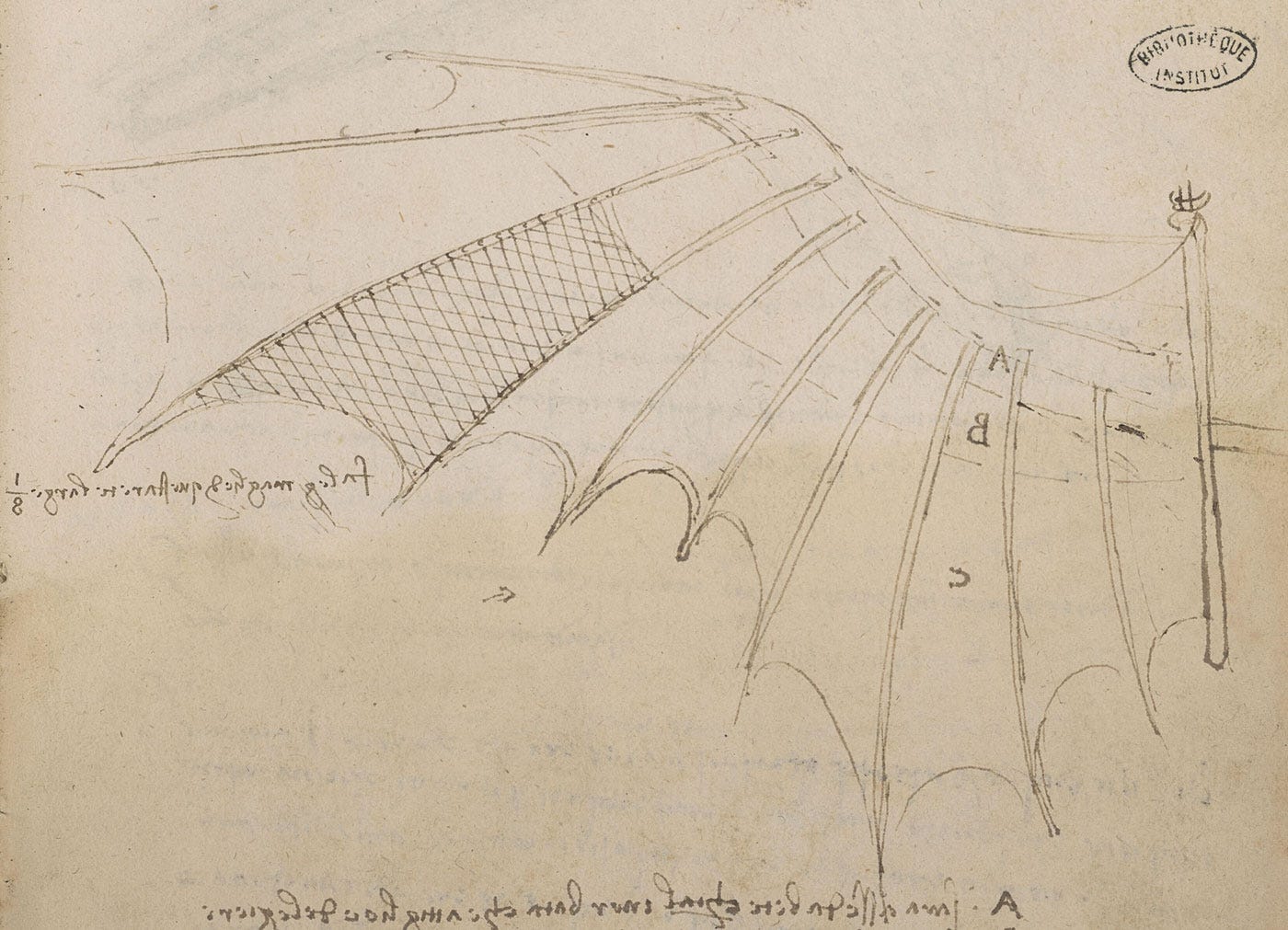

He has also written of the nature of water, and of divers machines, and of other matters, which he has set down in an endless number of volumes, all in the vulgar tongue, which, if they be published, will be profitable and delightful.

An 'endless' number of volumes that would be useful to mankind if published.

Art and science: two sides of the same coin for Leonardo da Vinci

We tend to see Leonardo's scientific, engineering, and medical endeavors as completely separated from his work as a painter.

If Leonardo were here today, he would insist that the two are intertwined. That is why we will not differentiate between art and science when we look at his notebooks.

How much of Leonardo's drawings survives?

Dear reader, I regret to tell you the truth: we have around 7,000 pages by Leonardo da Vinci today. It may look like a considerable number, but only one-quarter of Leonardo's output. You do not need to take my word for it.

There is the great art historian Kenneth Clark:

Only about a quarter can still be read in Leonardo's hand; three-quarters were in notebooks now lost.

The British Library curator specialising in the 1450–1600 period:

With his vast written output —it’s estimated he produced 28,000 pages of writing, of which only about 25% survives today— Leonardo was a significant ‘author’ by any standards.

These numbers do not come from thin air. Another scholar counted a list of 1,008 chapters, with only 235 surviving. That is a 77% loss. What happened?

How is it possible that three-quarters of Leonardo's notebooks are lost?

Leonardo da Vinci died in France in 1519 and bequeathed all his books to his assistant Melzi, who returned them to Italy.

For fifty years, with the help of two assistants, Melzi attempted to organize the mountain of papers in front of him. Remember that Leonardo wrote in reverse, so one had to use a mirror to read what he wrote before copying it.

Melzi did succeed in organizing one book, the Treatise on Painting. Although it was only published 130 years after Leonardo's death, it proved immensely influential.

All papers and notebooks were bequeathed to Melzi's son, a lawyer, who had zero interest in his old man's heirlooms. He had no idea how valuable they were, how people started to steal the books from his attic. An honest man tried to return them, and this happened:

Dr Orazio Melzi, who was very surprised of the predicament I brought unto myself, gave them to me while saying that he had of the same painter many other drawings that remained abandoned in trunks in the villa’s attic.

Melzi cared so little about Leonardo's books that he gave them away and stored the rest in trunks. Please note that it does not say one trunk but several. Word got out.

Told those who saw them how easily I obtained them, in a way that many people returned to Dr. Orazio’s house and took drawings, anatomical models, and many precious relics of Leonardo’s workshop.

That is how three-quarters of Leonardo's papers were scattered, abandoned, and left to rot. The surviving quarter was often cut into pieces to be sold individually.

There are times when it seems fair to ask that if instead of being homo sapiens—sapiens means wise—we should rebrand ourselves as homo stupidus.

Leonardo da Vinci's genius was forgotten for centuries

Inventions and discoveries are all good, but they are useless if no one knows about them, precisely what happened to Leonardo's inventions. Leonardo's biographer wrote that his death meant that 'the loss was incalculable.'

Maybe we can try to measure it, as three-quarters of his thoughts and studies are gone. As to what remained, the issue is to know about it by printing and publishing Leonardo's books. In a book on Engineers and Engineering in the Renaissance, we read:

Had Leonardo contributed nothing more to engineering than his plans and studies for the Arno Canal, they alone would place him in the first rank of engineers of all time.

Dear reader, the bad news is that Leonardo's papers only started to be edited and published in the 1800s. This means that for centuries, most of his genius was never put into practice or passed on to others to be useful and improved upon.

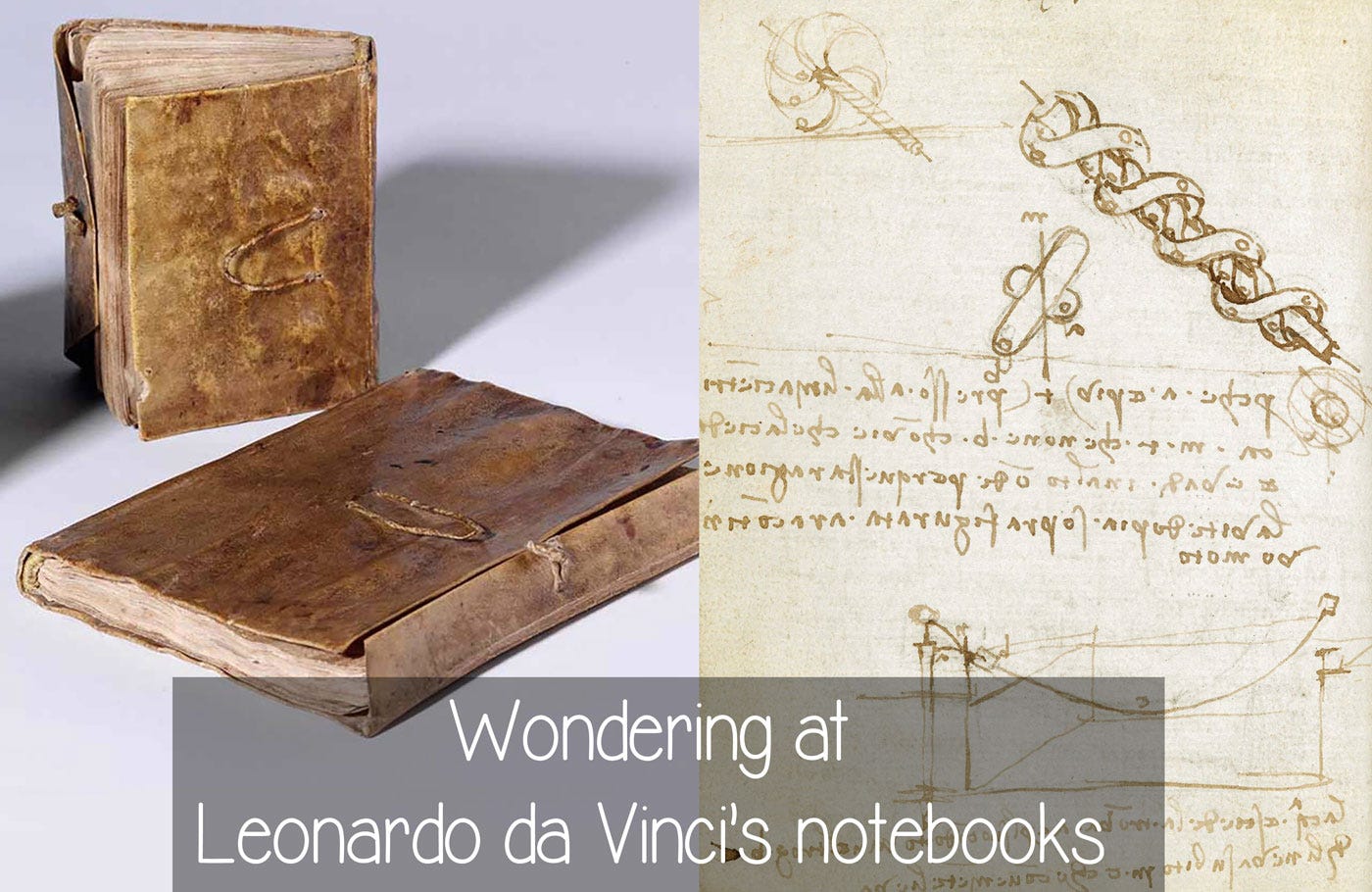

The myth of Leonardo crafting flying machines and helicopters exists only on TV. These fantastic contraptions were buried deep in thousands of papers that were not shared and had never been built.

We will never know what astonishing things are contained in the lost three-quarters. Only in the 1800s did people realize that Leonardo did much more than the Last Supper and the Mona Lisa.

Rarity, fragility, and awe

Dear reader, these stories are there to make you feel in awe, not to feel sad. Yes, most of Leonardo's genius has been lost due to stupidity and greed, but now is the time to wonder at what survives.

One must accept that works on paper are very fragile. If you ever forgot a newspaper by a window, you saw how sunlight quickly turned white paper yellow. Now that you realize Leonardo's notebooks are rare and fragile, let's discuss how to enjoy them.

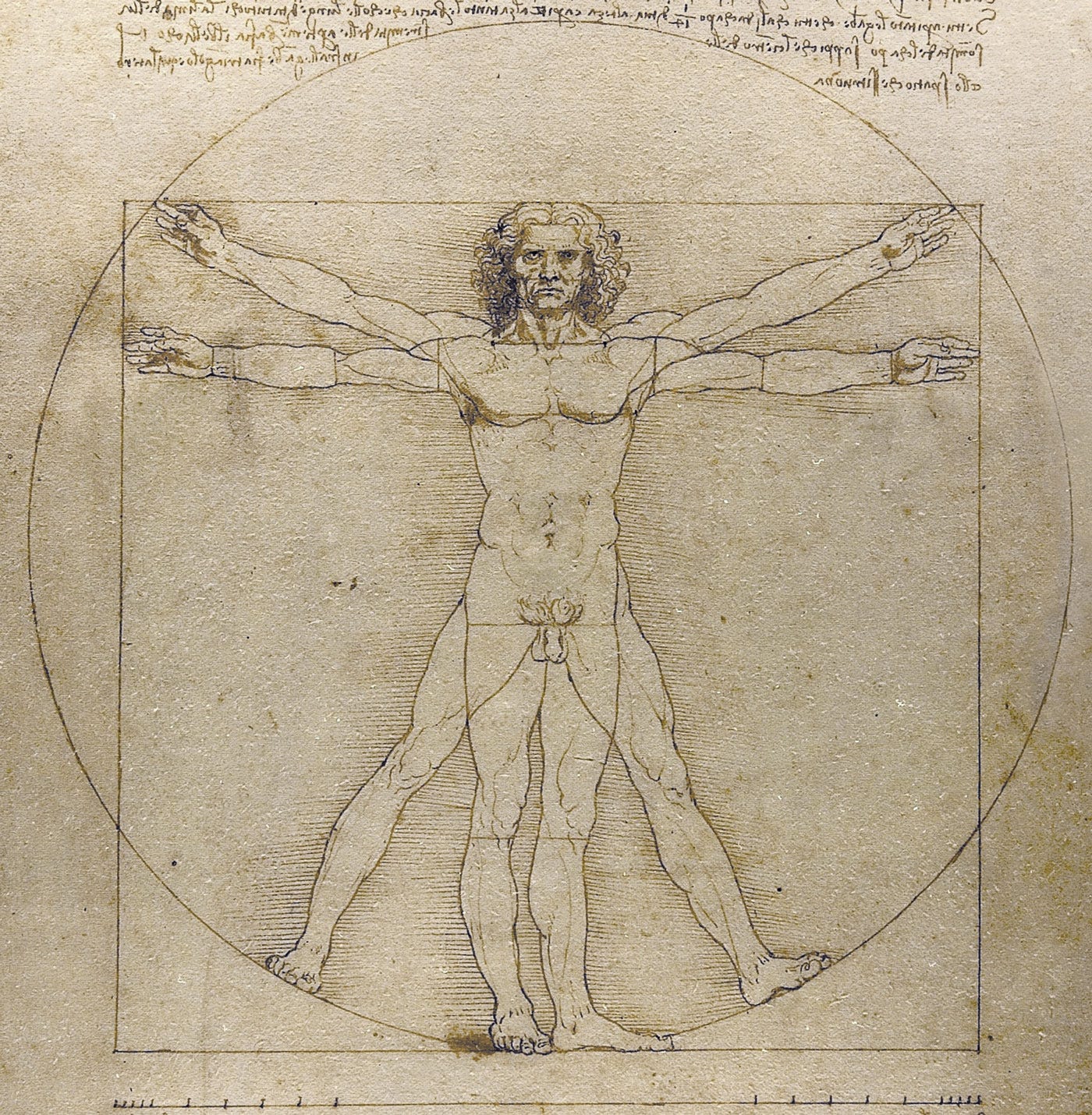

Opportunities to see Leonardo's drawings are scarce. For example, the famous Vitruvian Man sketch came to Paris for the 500th anniversary of Leonardo's death. It is only displayed on rare occasions. I was lucky to see it, but it was either behind someone's head or with phones shoved in my face.

Whenever I tried to see the drawing—that is, not glancing for three seconds but wondering at it—the throng of people lining up behind me made me feel like some pervert, upset that I was ruining their 'I was there' social media post.

That is where, dear reader, the good news comes with practical advice on enjoying Leonardo's notebooks comfortably. You can wear your pajamas, drink your favorite cocktail without being judged, and bother no one.

Below is a list of links to spend countless hours online looking at Leonardo's notebooks in high definition.

Wondering endlessly at Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks

Trying to follow Leonardo's mind, one realizes it was like a butterfly fluttering from one subject to another, never finishing the thought, to go and marvel at the swirls of a river or a flower.

His biographer told us:

Because of Leonardo's understanding of art, he began many projects but never finished any of them, feeling that his hand could not reach artistic perfection in the works he conceived, since he envisioned such subtle, marvelous, and difficult problems that his hands, while extremely skilful, were incapable of ever realizing them.

Inside Leonardo's dreams were things too beautiful and creative to be transcribed by hand, even by a skilled hand like his.

This is why spending hours, days, or more browsing these notebooks in contemplation offers a window to these marvelous things in his mind.

And about contemplation and imagination, Leonardo da Vinci had this advice:

I shall not refrain from including among these precepts a new aid to contemplation, which, although seemingly trivial and almost ridiculous, is none the less of great utility in arousing the mind to various inventions.

And this is, if you look at any walls soiled with a variety of stains, or stones with variegated patterns, when you have to invent some location, you will therein be able to see a resemblance to various landscapes graced with moutains, rivers, rocks, trees, plains, great valleys and hills in many combinations.

Entering Leonardo's mind, letting his genius prompt you to contemplate and invent, in your mind, striking images.

Maybe not as fast as AI, but way more inventive and poetic. That would be the great Moment of Wonder.

The List of Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks online in high definition:

While I will always advocate that the real thing is superior to the photo, Leonardo's notebooks are the exception. They are small and extremely fragile; even if you are lucky enough to see them, they are behind glass, and it is impossible to turn the pages.

Here is a selection of notebooks available online, to spend hours in awe at Leonardo da Vinci's genius:

Library of Congress:

- Codex on the Flight of Birds.

London, Victoria & Albert Museum:

Paris, Institut de France:

Once you click on individual names, you have the entire book online, for example:

Milano, Biblioteca Ambrosiana:

Milano, Archivio Storico Civico e Biblioteca Trivulziana.

Spain, Madrid Codices at the Biblioteca Nacional de España

Sources

Leonardo da Vinci: from manuscript to print.

Leonardo’s legacy: an international symposium, Berkeley, Calif., University of California Press, 1969. Ladislao Reti, Leonardo the Technologist.

Le Memorie su Leonardo da Vinci di Don Ambrogio Mazenta, ripublicate ed illustrate da D. Luigi Gramatica.

William Barclay Parsons, Engineers and Engineering in the Renaissance, MIT Press, 1939.

Leonardo’s Notebooks, Kenneth Clark.

The strange vicissitudes of Leonardo's manuscripts.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the artists.

Leonardo on Painting: An Anthology of Writings by Leonardo Da Vinci, with a Selection of Documents Relating to His Career as an Artist.

https://www.gallerieaccademia.it/en/study-proportions-human-body-known-vitruvian-man