Impressionism's Unsung Master, Caillebotte

How one of the most important painters of the 1800s had unfairly been forgotten

Dear reader, you may not know Caillebotte's name, and you are forgiven. It is hard to pronounce in English, as it sounds like Key - eye - bot.

In the story "When Impressionism was seen as hideous daubs," we discovered the years of financial struggle that Monet, Renoir, and others endured.

They had a good friend in Gustave Caillebotte, a well-off man who helped them financially.

Caillebotte, as a generous benefactor, likely saved Impressionism. In its first ten years, he ensured that his fellow painters could afford a roof over their heads and food at the family table, as many had children to provide for.

He also purchased 70 masterpieces, which he meant to gift to museums. But even twenty years after the birth of Impressionism, it was difficult to convince museums to display what many still regarded as 'hideous daubs.'

That is why officials only accepted 40 of the 70 masterpieces Caillebotte generously offered.

At his death, his friends insisted that:

He truly was a rare companion, of absolute self-denial, thinking of others before thinking of himself, if he thought of himself at all.

Caillebotte did not even attempt to secure his legacy by including his paintings in the gift. That is why he has unfairly been relegated to being a footnote in the history of Impressionism.

Now, it is time to marvel at the artist Gustave Caillebotte.

A young artist rejected by the Salon's official exhibition

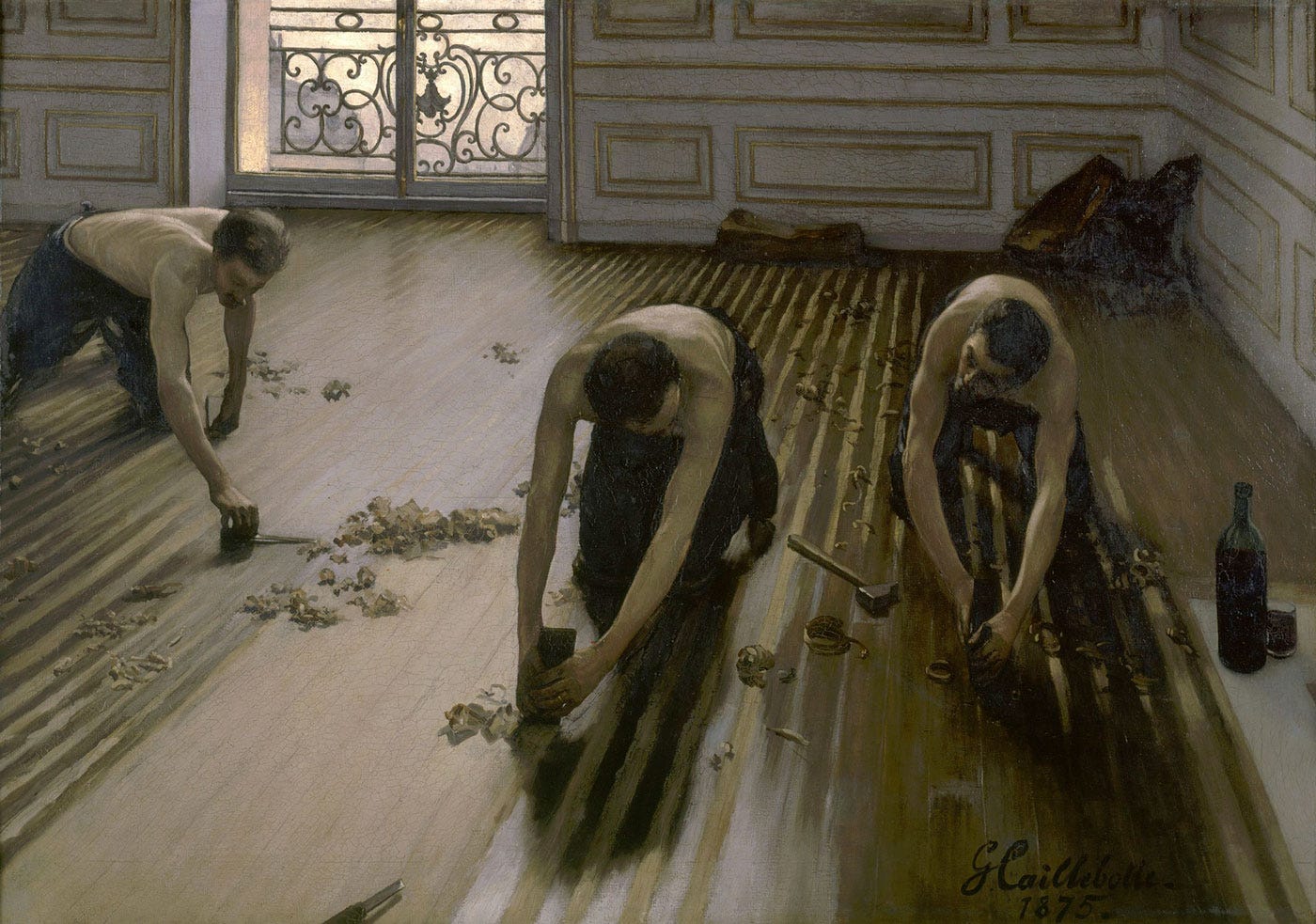

Born into a bourgeois family, young Caillebotte chose to become a painter, learning from academic painters. He likely visited the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874 and proposed the Floor scrapers to the official Salon the following year.

The daring, photographic view of a "vulgar subject matter" ensured his rejection. But in those days, being rejected meant one was doing something right.

That is how Caillebotte was invited to participate in the Second Impressionism exhibition. Important detail: since the word Impressionism is an insult, the exhibitions were simply titled 'Painting Exhibition.'

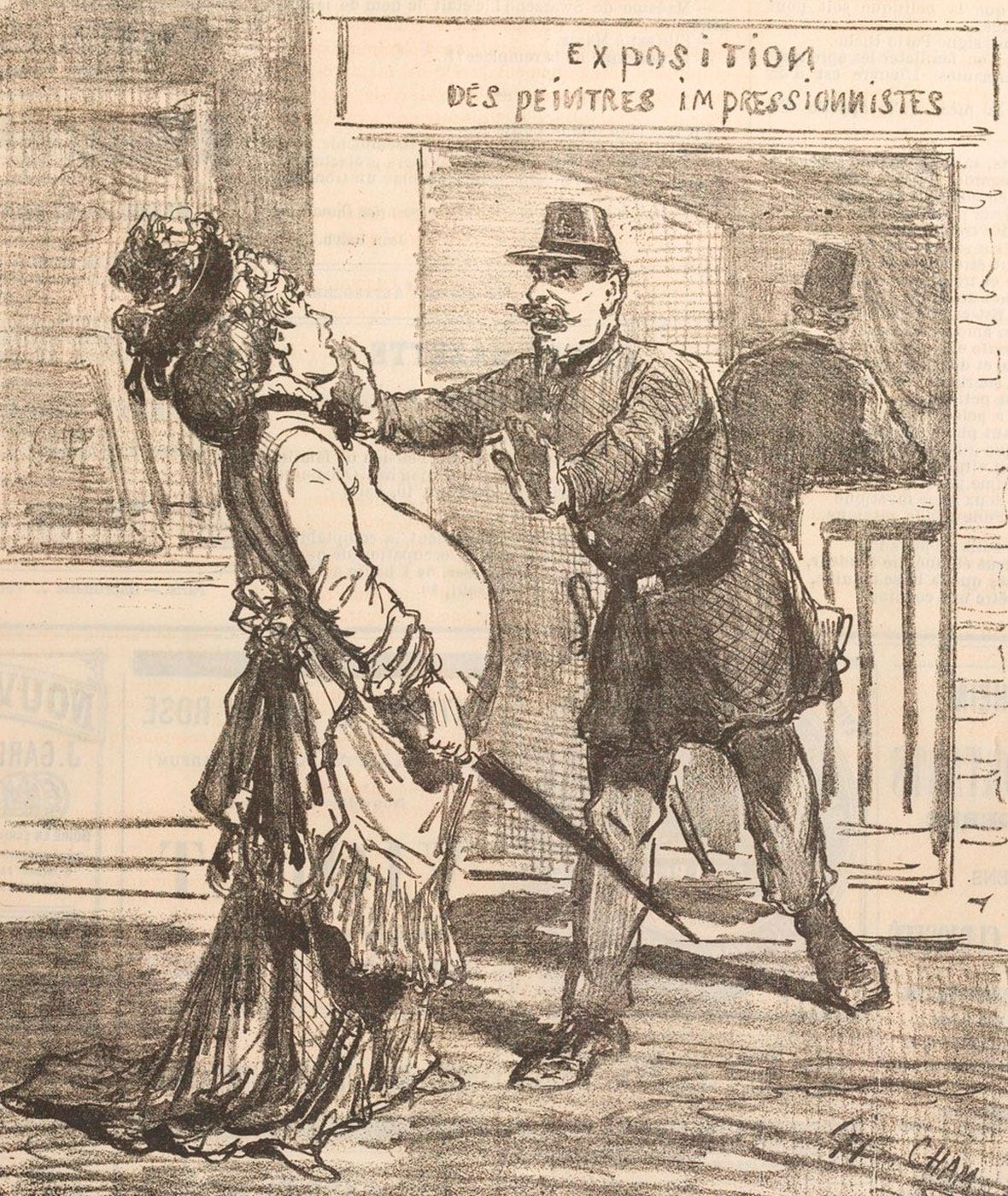

And the media's reaction was a lot worse than the first.

Second Impressionism exhibition, second disaster

For the second exhibition, the press threw the word Impressionist or Impressionalist as:

Barbarism worthy of serving as sign for barbaric art.

Below is a translation of the front page of one of the most important French newspapers reporting on the Second Impressionist exhibition:

The rue Le Peletier is out of luck. After the fire at the Opera, a new disaster struck the neighborhood.

An exhibition opened at Durand Ruel, said to be of painting. The harmless passerby enters, and a cruel spectacle is offered to his terrifed eyes.

Five or six lunatics, including a woman, a wretched group taken by the folly of ambition, have gathered there to exhibit their work.

There are people who giggle at these things.

These so-called artists call themselves the intransigents, the Impressionists; they take canvases, color and brushes, randomly throw in a few tones, and sign everything.

Here is the heap of vulgar things we publicly expose without considering the fatal consequences.

Yesterday, a wretched man was arrested on rue le Peletier, who, leaving that exhibition, was biting passersby.

The critic ends by suggesting that an "artistic clown" should be put at the door of this "appalling spectacle."

I trust, dear reader, that it makes sense now that the label 'Impressionist' is meant as a slur.

Caillebotte, a modern, photographic eye

In an age when many see the world behind a small rectangle, taking images of everything and anything in front of them, it is hard to perceive how revolutionary these images were.

A quick recap is needed. Photography was only 30 years old in the 1870s, and although it was acceptable for portraits, it was seen as a mechanical process, not an art form.

Tubes of paint, invented at the same time as photography, allowed the artist to paint outside for the first time. For most people, whether in painting or photography, it was utterly shocking to pretend that an image of someone waiting for a train or sitting at a café terrace could be art.

Art is about serious matters, religion, history, and moralistic scenes. How can it be blurry and depict the mundane, such as waiting for the train or digesting a Sunday lunch?

Aside from the fact that the new artists were often interested in photography, there is another reason for the daring framing of these paintings: Japanese prints.

Until the 1870s, Greek and Roman art were the primary influences on art. Now, Japan trades with the West, the bourgeois buy expensive vases, and artists buy cheap prints.

From Manet to van Gogh, all modern painters were influenced by the' strange perspective and color effects of Japanese woodcuts.

Those born before the advent of the internet and smartphones know that both have changed how we view the world. It would be foolish to ignore their effects, good or bad.

The same goes for the train, Japan, and photography in the 1870s.

Depicting the modern world, the boulevard, the train station

Most of old Paris was destroyed to make way for the boulevards, which are wide streets with straight lines lit at night. Consider the train station as exciting as an airport, photography as revolutionary as social media, and the boulevard as the peak of modernity.

Degas's eye was drawn to the opera and dance, Monet to the ever-changing aspects of color.

Caillebotte, among other things, saw and painted the diagonals of the street and the metal beams of the bridge, in awe of the modern world appearing all around him.

Moments of leisure

Sunday afternoon boating

Like his dear friend Renoir, Caillebotte transports us to these moments of pure relaxation, boating or swimming in the river outside Paris on a Sunday afternoon.

Gustave Caillebotte, one of the most important painters of the 1800s

To conclude this journey, we will be like Caillebotte and first mention others. If we were to draw a list of the most influential large-format paintings of the late 1800s, the shortlist would include:

Renoir's Bal du Moulin de la Galette, today in the musée d'Orsay, thanks to Caillebotte's bequest.

Seurat's A Sunday on La Grande Jatte, exhibited at the last Impressionist exhibition of 1886.

And Caillebotte's Paris Street; Rainy Day, painted in 1877.

This masterpiece illustrates the tragedy of Caillebotte's relegation to a footnote in the history of Impressionism. It remained in the Caillebotte family for a long time, only to be revealed to the public in 1964 when the Art Institute of Chicago bought it.

In other words, this painting was out of view for almost 90 years, meaning that while Monet, Renoir, and van Gogh were familiar to the general public, Caillebotte's was known only by a few.

Now, dear reader, let me share a personal Moment of Wonder.

Although I knew this painting by its photographic reproduction, and have long admired it, I had never seen it in real life. After years of waiting, it traveled to Paris.

Familiar with the wonderful Floor scrapers at the musée d'Orsay, I thought it was about the same size, around a quarter smaller than life size. Here I was, confident that having seen tens of thousands of artworks in real life qualified me to imagine what an artwork looks like from its reproduction.

How wrong I was. When I entered the Caillebotte exhibition in Paris and first laid eyes on it, I choked up. I was floored, having no idea it was life-size. I found myself in front of a time portal, a point-of-view scene transporting me to that fleeting moment under the rain 150 years ago.

One day, I should write a story about the vast gap between a reproduction and the real thing.

In the meantime, although this story only reproduces Caillebotte's masterpieces, I hope these words helped you get a Moment of Wonder.

Sources

Le Figaro, 3 Avril 1876, Albert Wolff about the Impressionists: translated and edited into English for this story.

Gustave Geffroy, la vie artistique, troisième série, 1894, translated for this story.

https://artjourneyparis.com/private-tours-orsay-museum.html