When Impressionism was seen as 'hideous daubs'

A journey back in time to realize how much Impressionism was rejected

Dear reader, we climb aboard the time machine and land in 1874. Walking the streets of Paris, we soon realize that what we hoped to see, masterpieces by Monet, Renoir, and Degas, are nowhere to be seen.

The reason is that the Academy of the Arts, which has spent the last ten years fighting tooth and nail to prevent the emergence of a new style of painting, is so influential that it effectively has the right of life and death over artists’ careers.

The official Salon exhibition is the primary platform for artists to exhibit their art. If no one can see their paintings, no one might consider buying them; hence, starvation is certain.

Monet, a desperate young father worried that he could not afford to feed his son, tried to commit suicide by jumping into the Seine.

He might not have swum back to the surface had he known there would be twenty more years of financial difficulty.

Monet's financial struggles

In old age, Monet reminisced about his years of struggle.

One day I had to sell for three hundred francs a picture by Renoir which he had given me. I wrote explaining to him that I had needed food. He understood.

I owed a few hundred francs to a butcher. I knew that the bailiff was going to seize my canvases—I had about two hundred of them—so I slit them all with a knife.

When I came back a few weeks later to settle up with my butcher I found that they had been sold in lots of fifty, at thirty francs a lot, at about 60 centimes a piece!

Monet was so broke that he had to accept his father's offer of free food and lodging on the condition that he separate from his wife. As a result, he could not even afford to travel to Paris to see his newborn son.

About the suicide attempt, we have a poignant letter where Monet asks a friend for financial help:

I have just been thrown out of the inn, and stark naked at that. I've found shelter for Camille and my poor little Jean for a few days in the country. I don't even know where I will sleep tomorrow.

I was so upset yesterday that I did the mistake of throwing myself into the water. Fortunately, no harm came of it.

There was also a time when Monet had to give a painting as a deposit to secure rent, which he could not repay, and the painting was left to rot in the basement.

It was only at age 44 that he finally settled that debt. And it was only at age 50 that he enjoyed financial security by purchasing his home in Giverny.

This is why we need to discuss financing the birth of Impressionism.

Traveling to 1874 Paris

Opening the door to the time machine and finding ourselves in the 1870s, it is still hard to comprehend the world where the masters we revere lived.

For centuries, painters have tried to mimic reality, and photography does it better than they can. Speed was a horse galloping, and here comes the train and the railway stations, new cathedrals of steel and glass.

Times were changing, but art authorities, journalists, and the general public expected art to ignore the revolutions in politics and technology around them. Artists were supposed to copy the past, not to depict the present.

Exhausted by years of having to make their case, a group of artists in their 30s, most of them with families to provide for, finally thought out of the box. Why wait to be accepted into the Official Salon?

They created a company, rented a space, and organized their exhibition. No judges would turn them down, and visitors would not get migraines looking at a floor-to-ceiling jumble of paintings.

Instead, there would be only two or three paintings per wall, presenting scenes never depicted in human history: a street, people at the opera, even ladies ironing shirts.

The horror! Young artists looked out the window and painted the world around them. Stepping outside the studio was to prove very costly.

A financial disaster called Impressionism

Dear reader, to help you understand the situation, memorize a simple number: 100 francs is equivalent to roughly $500 today.

A motley crew of artists cobbled together a budget of over 9,000 francs to organize an exhibition. That covered the rent for a studio a stone's throw from the Opera, the most fashionable area of Paris, and a catalog, all in the hope of selling their artworks.

The profit was about 900 francs, only 10% of the investment. Only four paintings were sold: Monet got 200 francs, Renoir 180. In other words, the exhibition brought them no profit and a lot of trouble.

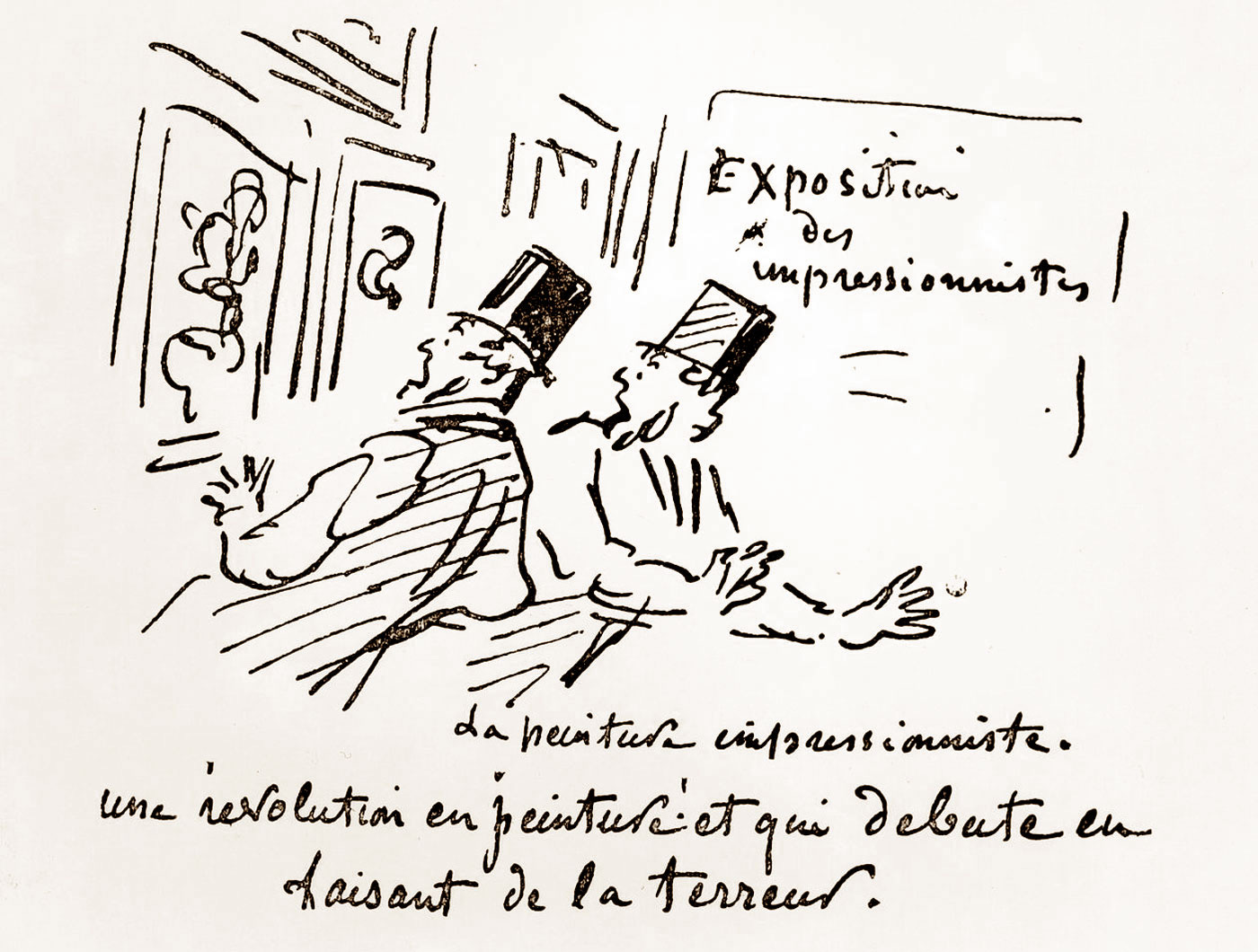

It gets a lot worse, as a journalist came to the exhibition and, playing on Monet's Impression, sunrise, coined the term Impressionism as an insult.

Every time the word Impressionism was in newspapers, it was to denounce it as:

Hideous daubs. An affront to artistic decency. A war against beauty.

The impression given by the Impressionists is that of a cat walking on the keyboard of a piano or a monkey who snatched a box of colors.

To compensate for the enormous losses, the artists auctioned their paintings. There was so much outrage at the fact that hideous daubs were on sale that police were called to prevent a fistfight.

The results were catastrophic: 70 paintings sold for 10,000 francs, just about covering the exhibition costs.

Monet and Renoir sold 20 paintings each; Renoir received around 100 francs per painting, and Monet twice as much. One Pissaro sold for 7 francs, while the frame alone cost 50 francs.

The 40 Monet and Renoir paintings sold for the equivalent of $35,000!

Unfortunately, time travel is only possible in our imagination. Otherwise, instead of trying to prevent the sale on the day of that auction, the police would be called to stop us, time travelers, from breaking down the door to get in.

For the price of a basic car, we could get an entire museum's worth of Impressionist masterpieces.

Gustave Caillebotte, Impressionism's benefactor

Dear reader, consider Monet's situation. At age 43, he could not afford the train fare to Normandy for his family. For the Impressionists, financial security only came in their late 40s, after 25 years of difficulties.

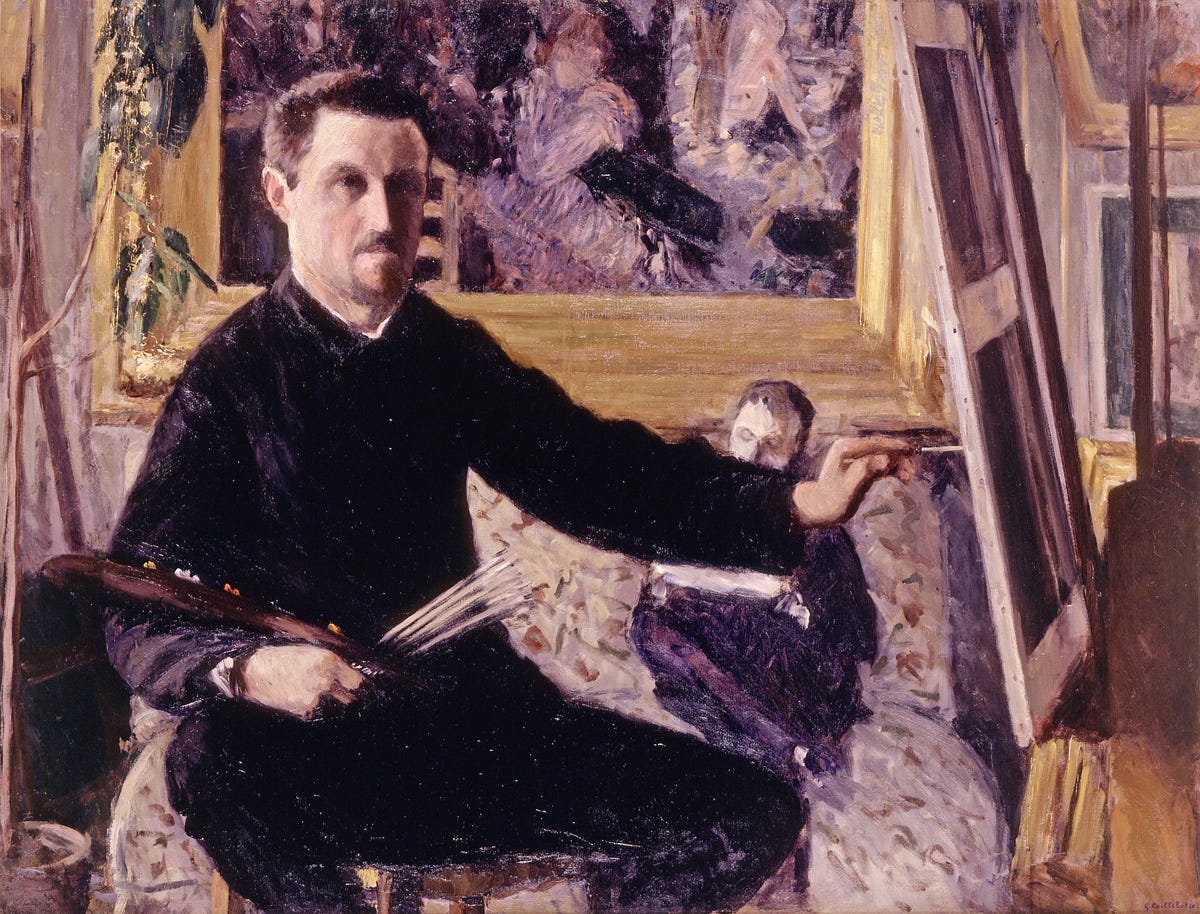

That is where we need to pay homage to the few people who supported these artists during their long years of struggle. One of them was Gustave Caillebotte.

Here is a profile of the man from those who knew him.

In 1875, a newcomer, Gustave Caillebotte, himself a painter, provided the Impressionists with financial support that came in very handy for some of them.

Caillebotte was wealthy, generous, and a man of taste.

He was a devoted friend, whose effective assistance was always done with such a delicate manner that it seemed as if it were him whom those in his debt were rendering a service.

Caillebotte did not just help finance the Impressionists' further exhibitions; he also helped the very creation of art by helping his friends afford to pay rent, settle their debts, and encourage them.

He also bought paintings, not as a speculator, but as a friend. In a letter to Pissarro, he wrote:

I sent you 1,000 francs instead of 400.

Imagine the difference that makes when you struggle to pay rent and feed your family.

Caillebotte's attempt at giving 70 masterpieces, for free

In a few years, Caillebotte gathered a collection of 70 masterpieces by Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Sisley, Degas, and Cézanne.

A visionary both as an artist and as a collector, he wrote, at only 28 years old, a testament where he proposed to give everything to state museums, with one condition:

I want this gift to be accepted so that these paintings do not end up in an attic or a provincial museum but rather in the Luxembourg and later in the Louvre.

He knew of the possibility that the gift would be turned down, so he added:

A certain lapse of time will be necessary before the execution of this clause, until the public may, I do not say understand, but admit this painting.

Twenty years or more might be required.

He never considered putting himself above his friends and did not even put his paintings on the list.

Caillebotte died in 1894, aged 45, and asked his friend Renoir and brother Martial to negotiate the bequest.

In the 1890s, Impressionism still was, for many, nothing but 'hideous daubs'

If you offered such a collection for free today, curators and art collectors would jump into a crocodile-filled river to get it. But then the response was tepid, fearing the conservative-minded would throw a fit.

One example was an academic painter who went wild:

For the State to have to have accepted such trash is a moral stain ... arnachists ... crazy ...

Another recommended that these painters get a good kick in the bum. Traditionalists were angry because the gift meant the paintings would end up in the Louvre, and having ‘daubs’ near Old Masters was too much for them.

In the end, the State accepted only 40 of the 70 paintings.

Imagine turning down masterpieces by Monet, Pissarro, and Degas! It gets worse: in the 1900s, Caillebotte's brother tried several times to offer the rest. Being turned down again angered him so much that he made his family swear to forget about it.

So, in 1928, when an attempt was made to ask if it was still possible to be gifted the rest, the answer was no.

That is why, nearly fifty years after the birth of Impressionism, Dr. Barnes managed to purchase the second-largest Impressionist art collection in the world.

Pondering Monet and Renoir's tenacity in the face of years of hardship was, I trust, a Moment of Wonder.

Next, with “Impressionism’s Unsung Master, Caillebotte”, we will discover how Caillebotte, long relegated to the footnote of Impressionism, was also a major artist.

Sources

Monet’s letter about the suicide attempt is translated from French in “Bazille et ses amis” by Gaston Poulain, Monet’s letter to Frédéric Bazille, on the 29th of June 1868.

Georges Rivière. Renoir et ses amis. Paris: H. Floury, Éditeur, 1921.

René Gimpel, “At Giverny with Cl. Monet,” Art in America, June 1927.

John Rewald, Histoire de l’Impressionisme.

https://www.musee-orsay.fr/fr/magazine/2024-10-03/le-legs-caillebotte-une-affaire-delicate

Paris 1874 : the Impressionist moment, The exhibition of 1874 : a commercial failure? Léa Saint-Raymond.

https://artjourneyparis.com/private-tours-orsay-museum.html

https://impressionist1877.tripod.com/caillebotte_bequest.htm