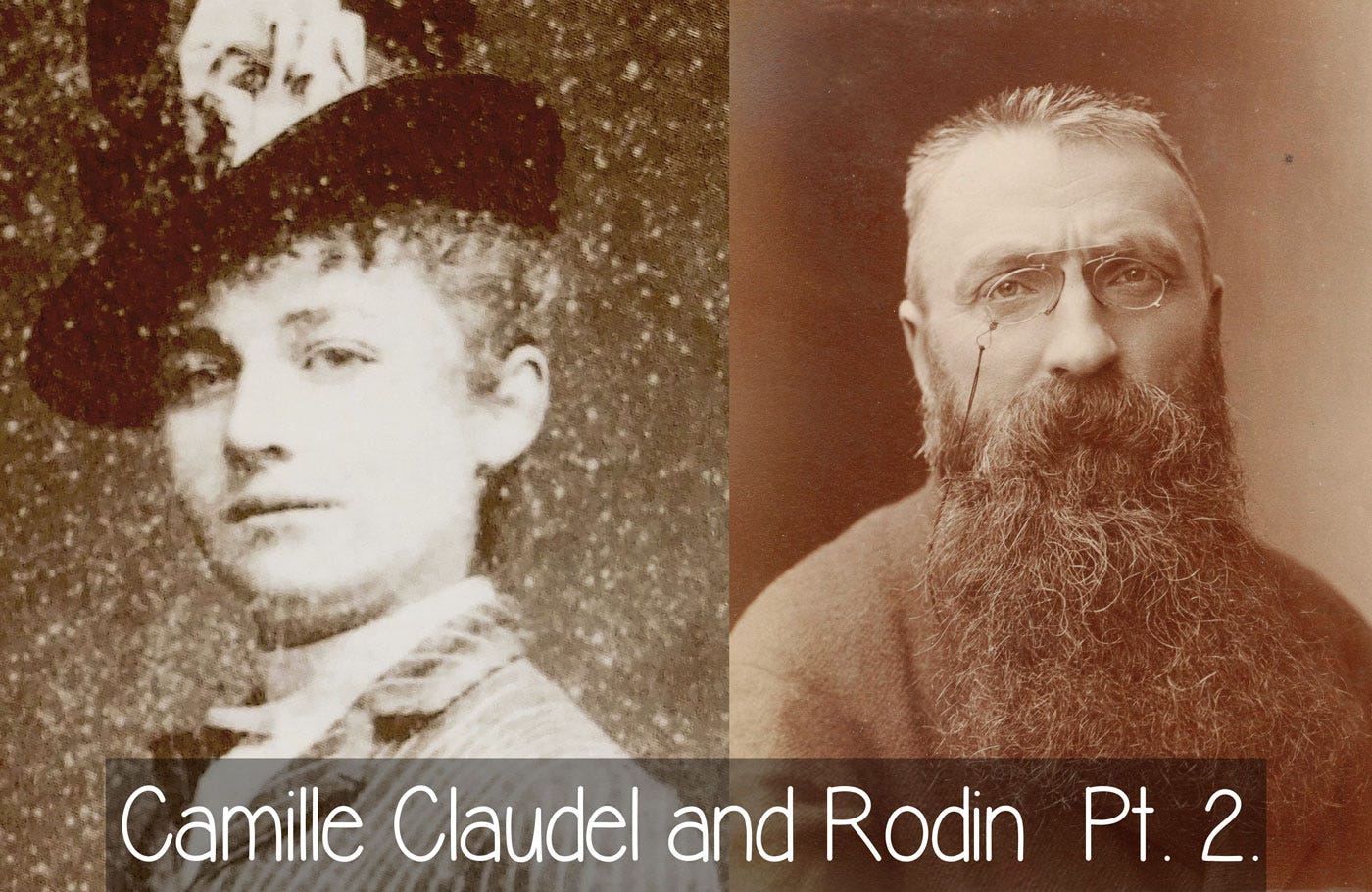

Camille Claudel and Rodin, a love story ending in tragedy.

Oblivion and rediscovery for a woman of genius, Camille Claudel.

Dear reader, as we discussed in the first part of this story, Rodin did not become an artist until he was 40. Once a master, he shared his knowledge with younger sculptors, which is how he met Camille Claudel.

Let us now contemplate the contrast between them. He is twenty years older, and it took him the same time to become a master. It was difficult for him, but she started as a little girl. Her work impresses him, so he takes her on as an assistant. She challenged him artistically.

And she is beautiful. Inevitably, Rodin fell madly in love. The attraction between their minds and bodies was as intense as lightning.

Rodin's tears

To say the relationship was passionate is an understatement. Rodin wrote to his fearsome friend these words:

Last night, I wandered, for hours, in our favorite places, without finding you, how sweet death would be and how long is my agony.

Rodin even says he will abandon sculpture for her. And he begs:

Have pity, cruel girl. I can't go on, I can't spend another day without seeing you. Otherwise the atrocious madness.

It is over, I don't work anymore, malevolent goddess, and yet I love you furiously.

She changed his life:

I don't regret anything neither the end which appears like a funeral. My life will have fallen into an abyss. But my soul had its blossoming, late alas.

I had to know you. And everything changed into an unknown life, my dull existence burned in a bonfire.

Thank you because I owe everything to you, the part of heaven which I had in my life.

And the tears and pain:

You don't believe my suffering. I weep and you question it. I have not laughed in so long. I am already a dead man.

My dear one I am on my knees facing your beautiful body which I embrace.

While Rodin, in his letters, is on his knees, Camille addresses him, in their letters, as vous, as befits an elder or employer, and not tu, as one would to a lover.

Rodin signs a contract with Camille

Rodin signed an unprecedented contract laying out his obligations toward her. In it, Rodin agrees only to have one student, Camille, do everything feasible to help her career prospects, introduce her to influential people and journalists, and have no model other than her.

For their personal relationship, Rodin writes that if the contract conditions are met for six months, "Mademoiselle Camille will be my wife."

That was the culmination of Camille's standing as an artist and lover. For Rodin, the years with Camille by his side in the studio were among the great joys of his artistic life.

Separation

Camille's sculpture above, Mature Age, also called Destiny, seems to show a desperate Camille attempting to stop Rodin from leaving with Rose, his lifetime companion.

Camille Claudel spread her wings

Camille, with The Waltz, hoped to get a commission from the State to carve it in marble. The inspector coming to assess the work described it as a virtuoso performance equal to Rodin—high praise indeed.

Yet it illustrates that Camille's art is freed from Rodin's influence. One problem was that while it was acceptable for a man to carve nudity, it was not for a woman. The statue was turned down because it was "too realistic" and its "surprising sensuality."

Rodin wrote to the inspector to defend Camille's work, to no avail. Once she added drapery, it was accepted but never completed. Some critics praised her work; others attacked her as a mere Rodin follower.

A woman of genius

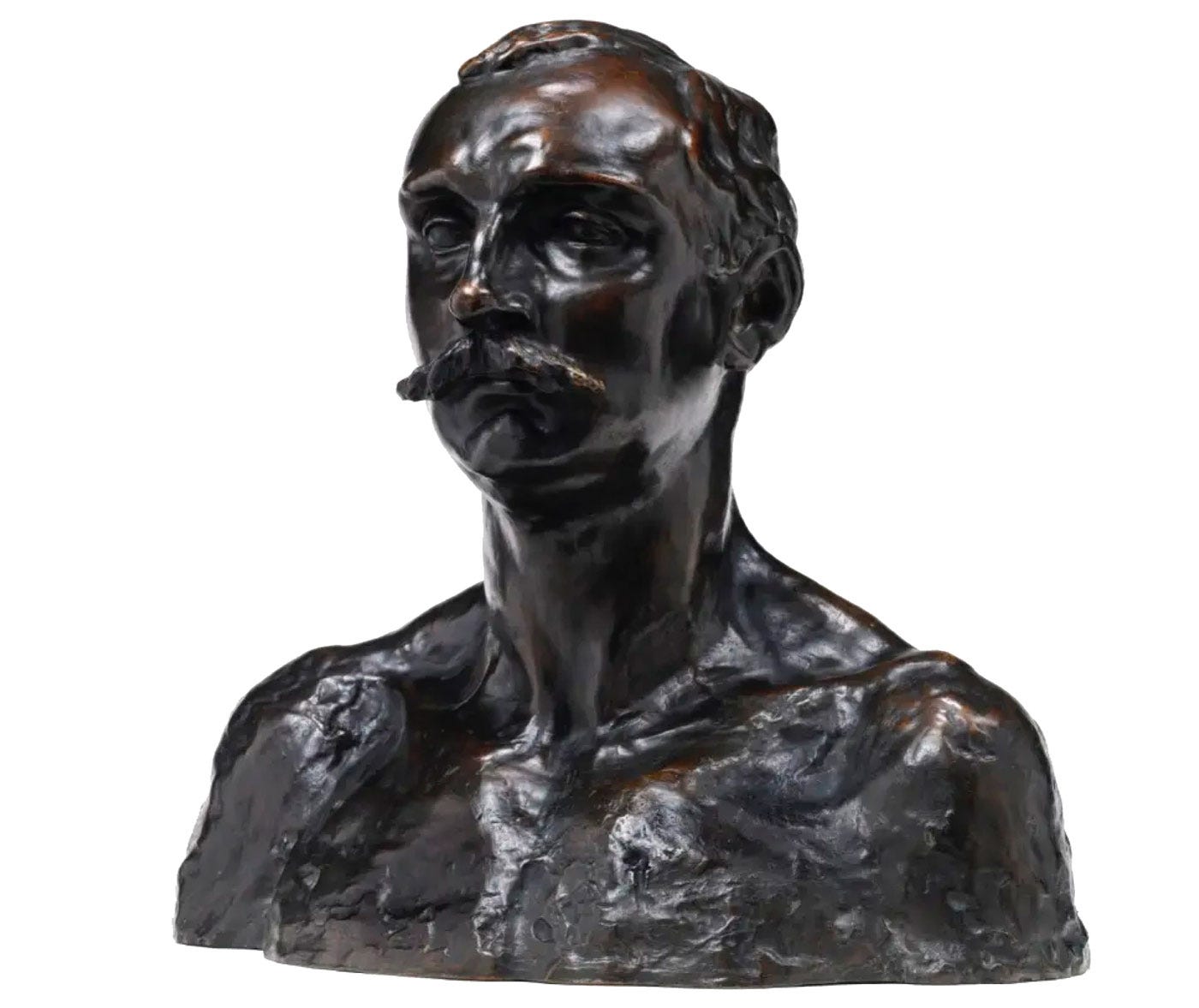

These are not my words but those of a journalist describing the sculpture above as a conversation:

- This work is that of a young woman, Mlle Claudel.

- Oh yes! She is, simply, a great artist, and this small group is the greatest work here.

Do you know we are in front of something unique, a revolt of nature: a woman of genius.

The journalist then states that it would be a crime not to have her work in museums and that she needs bread and money.

Rodin wrote to the journalist to praise the article, saying he had not spoken to her for two years and mourning that she is a misunderstood artist.

Rodin even wrote to another art critic:

Do something for this woman of genius (the word is not too strong) whom I love so much, for her art.

And Rodin found the strength to write to her about trying to get a minister to come to her studio:

It is in your strict interest that you don't waste your future. The sight of you scares me and would probably throw me into bigger suffering.

Rodin helped Camille without her knowledge

Unbeknownst to Camille, Rodin kept helping her, arranging for her to be invited to exhibitions and helping her sell her work.

He even tried to get the French President to come to her studio! She wrote back to Rodin to say she did not have the correct dress for such a prestigious visitor, a polite no.

Slowly, Camille sank into poverty, loneliness, and delusions. She sold a statue to her biographer without discovering that Rodin had provided the funds.

Paranoia and solitude

Rodin wrote to Camille that he worried about her. This time, he writes vous instead of tu.

Show your admirable works. There is justice, believe me. A genius like you is rare.

In the 1900s, an argument about one of Camille's sculptures broke off their friendship for good.

Rodin still used proxies to send her money, but eventually stopped when she publicly called him a crafty devil scheming behind her back.

She survived thanks to the money sent by her father. Her state worsened, and she even destroyed her work. She believed that Rodin schemed against her and wanted her dead.

Camille, the Claudel's family black sheep

Paul admired her work: "she is a woman of genius," but that is "in spite of the limited liking I have for her person."

That was because Camille had broken too many acceptable barriers for a woman. One of them was that she got pregnant from Rodin and resorted to an abortion.

Paul believed Camille was possessed and wondered about exorcism and sending her to the asylum. Camille still had one advocate in the family, her father, aged 87.

When their father died, Camille was not even informed. And in those days, all it took to send someone to the asylum was one medical certificate.

I, Doctor of Medicine, certify that Mademoiselle Camille Claudel is suffering from very serious mental disorders. She wears wretched clothes; she is extremely dirty since she never washes.

She is always afraid of 'Rodin's gang.' It is necessary to commit her to a mental institution.

Her mother asked that she be committed to the asylum:

She has done us a lot of harm. I am very happy to know that she is where she is, at least she can't harm anyone.

I previously used the word prison sentence. It is not an exaggeration; she was locked up in the regime of sequestration, closer to prison than medical care.

Camille did need help, but she paid a very steep price for stepping out of the bourgeois mold as an artist and a woman.

Thirty years at the asylum

Within days of her incarceration at the asylum, Camille wrote:

What was the point of working so hard and of being talented, to be rewarded like this?

Never a penny, tormented all my life. Deprived of all that contributes to happiness and still finish like this.

Camille's mother then asked for Camille's letters to be seized. She was mostly cut off from the world, still believing that Rodin wanted to poison her.

Risk of oblivion

Camille died in 1943 in a state of near starvation. During the occupation, 800 of the 2,000 patients of the asylum starved to death. Paul never came, and her body ended up in a mass grave.

Dear reader, maybe tears are streaming now. I promised you a Moment of Wonder; it will soon come.

After the Second World War, there was a risk that Camille Claudel's name and posterity would fall into the dustbin of art history.

Late recognition for Camille Claudel

In his last years, Rodin negotiated with the French state to donate his entire collection in exchange for his museum. One year after Camille's internment—Rodin was 74—he sent money to make her life more comfortable.

Camille's biographer suggested to Rodin: What about asking for a room dedicated to her in your museum? Rodin readily replied:

The idea of taking a few sculptures of Mademoiselle Claudel makes me very happy.

Camille did receive a letter describing what happened when Rodin saw her self-portrait kneeling statue:

I saw him stop suddenly in front of this portrait, contemplate it while softly caressing the metal and cry. Yes, cry. Like a child.

In his last moments, in and out of consciousness, Rodin asked about "my wife in Paris, has she got any money?" He probably meant Camille.

The musée Rodin opened, but without Camille Claudel's room. For years, Paul, still seething at Rodin and ashamed of Camille's behavior, refused to send the statues he owned to the Rodin museum.

Camille's biographer said:

Paul Claudel is an idiot. When you have a sister who is a genius, you don't abandon her.

Eventually, Paul started to feel remorseful. In the 1950s, he helped organize an exhibition dedicated to her and gave several statues to the musée Rodin.

Camille Claudel, a genius sculptor

It was only with a major Camille Claudel retrospective organized at the musée Rodin in 1984 that the artist returned to the public consciousness. Two movies depicting her life were produced.

A Camille Claudel museum opened in 2017 in Nogent-sur-Seine, where young Camille first worked with clay. Her sculptures regularly reach the seven-figure mark at auction.

As told in the story "The Joy Of Getting It For The First Time," I was brought, against my will, to the musée Rodin as a child and did not care for anything there until I saw her sculpture The Wave.

Camille Claudel's art is one of the things that led me to become an art historian. That is the reason why I was eager to share with you that she was more than Rodin's assistant and lover.

As Rodin himself stated, she was nothing less than a woman of genius.

I hope that realizing that was a Moment of Wonder, for you, dear reader.

NOTE : The asylum where Camille Claudel spent 30 years is only about 10 miles from where Vincent van Gogh spent one year.

Sources

Mathias Morhardt, Mademoiselle Camille Claudel, Mercure de France, 1898.

Odile Ayral-Clause, Camille Claudel: A Life. This is a fantastic book if you want to know more about Camille Claudel.