After the unscientific estimate that only 0,005% of artworks on display in the Louvre bear a smile, we discuss an even smaller amount, that of female painters.

Once, I was asked to do a tour of the Louvre based on female artists. I laughed and said I was happy to do it, but the visit would last 10 minutes.

That was guesswork, so I wanted to check.

Considering the size of the haystack—35,000 artworks—and the tiny needles, I turned to the Louvre website.

I should not have bothered, as I was already familiar with all the smiling portraits created by women in the Louvre.

It was easy, as the list fits on one hand: five paintings.

Or 0.00015% of the Louvre collection.

In this two-part story, we discuss some of the rarest treasures of the Louvre Museum.

Judith Leyster, the ‘Good company’

Context: what makes an artist important is their influence on other artists.

We already discussed Frans Hals with 'When Paintings Smile At You.'

Like Rembrandt, Hals is important precisely because he influenced others.

Judith Leyster worked in a crowded field with these two giants on the top steps.

Forgotten and painted over

The painting was offered for sale as a Frans Hals.

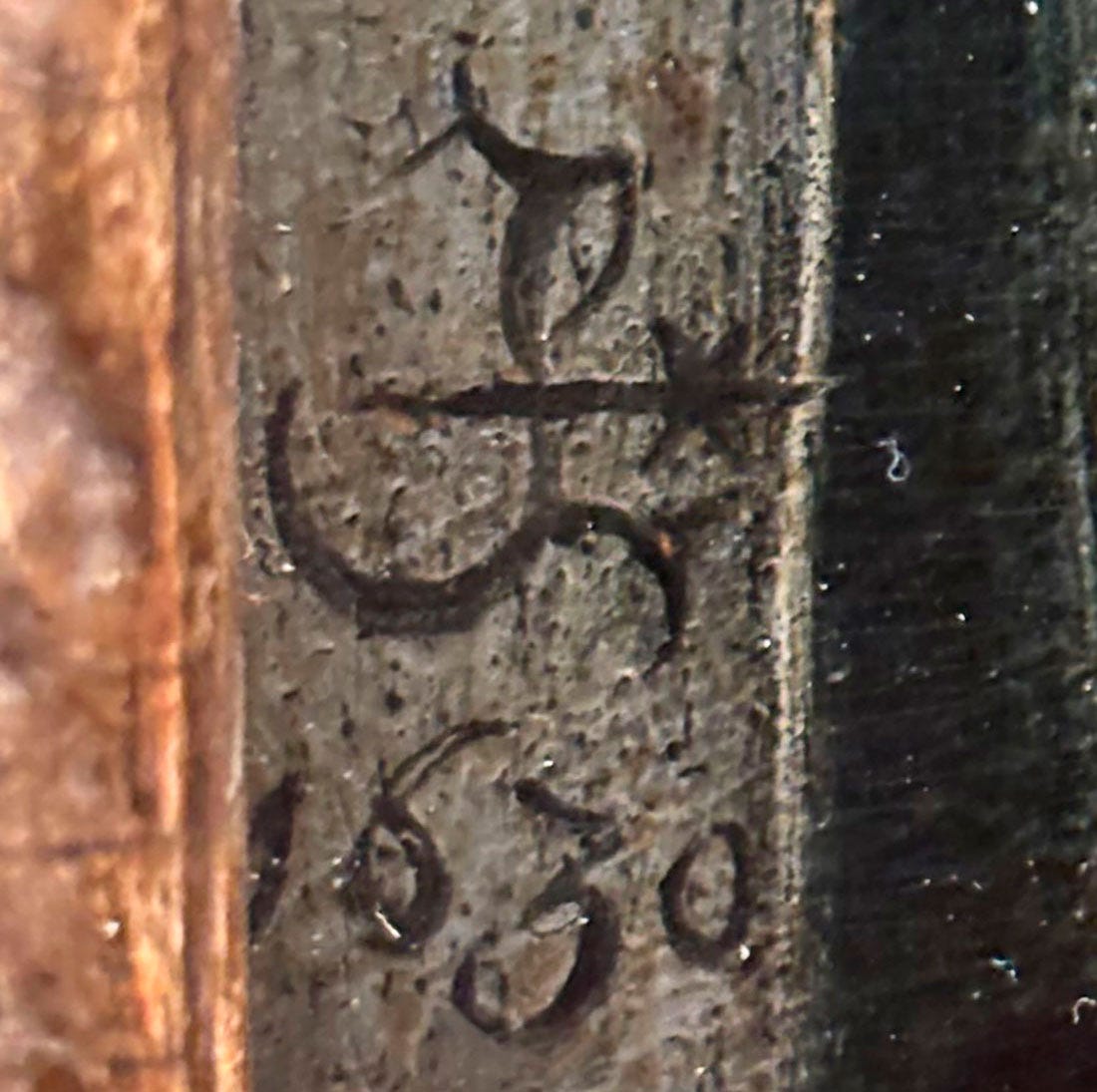

When the Louvre was asked to study the painting, its curators discovered the JL* signature (see below).

The original author's signature had been painted over.

It was bad news for the seller, who had to reduce the price, but it was an incentive for art historians to research who JL* was.

Who was Judith Leyster?

Probably the first woman accepted as a painter by the Saint Luke’s Guild of Haarlem.

That made her a master—someone who runs an independent studio and has assistants.

She became an independent artist at age 19 and a master at age 24.

This small painting is a 'genre scene'—basically, everyday life scenes.

Always keep in mind that these are meant as moralistic paintings, not to cheer you up.

Beyond the traditions of her time, Judith Leyster, looking at us from four centuries ago, seems to be a cheerful young lady, confident enough to paint her self-portrait at age 21.

Judith Leyster started to be rediscovered in the late 1800s, but mainly as a 'female Frans Hals.'

An article about her rediscovery, written by a woman, states:

Judith Leyster was the contemporary and fellow citizen of Frans Hals and the Dutch painters of his time, she came under his influence most of all, in fact so much that her style of work resembles his to the point of confusion.

Though she is never mentioned officially as one of her pupils, undoubtedly, she studied under him.

In other words, little else than an imitator.

Art historian note: When Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel, artists in Italy and beyond were under his influence.

Plain English translation: if you were an artist at that time, all you could do was enter the Sistine Chapel, fall on your knees, and weep.

Either you tried to paint like Michelangelo, or you changed careers.

Say you are a guitarist and are fortunate—or maybe unfortunate—to breathe the same air as Jimi Hendrix.

There's no escaping Jimi's influence. Does it make you a lesser artist?

Now, let's have a look at Judith Leyster's signature.

Her signature JL* is a play of words on Ley-ster, Dutch for "leading star."

This very painting helped resurrect her name and reputation.

Considering this example and the self-portrait were painted when she was 21, maybe it is not a stretch to call her a leading star.

Marie-Denise Villers

Bad news alert: fair or not, many artists fell through gaps in memory and history. Even great ones—a good idea for a future story!

Here, we have a painter who worked in the 'neo-classical' style, whose leader was David—the artist who painted Napoléon's coronation.

David also ran an important studio, where he taught hundreds of painters.

An entire generation, including two dozen women, learned from him.

As a result, many of them, including these women, lived in David's shadow.

That is the context for understanding what comes next.

Below is a painting in the Metropolitan Museum representing a woman artist at work.

It had been purchased as a David painting.

When it was thought to be a David painting, specialists praised it as:

Astonishing. A perfect picture, unforgettable.

But in the 1950s, curators realized it was not a David, downgrading it to a "less well-known artist."

In the 1990s, thanks to research, curators instead used her name, Marie Denise Villers.

Here she is below, in the Louvre:

If you wonder why the strange pose, the photo below helps.

Officially, its title is "A Study of a woman after nature".

Translated for you, here is the description of a witness during the Salon exhibition:

If it does not offer a precise portrait, one recognizes nevertheless that Madame Villers took herself as a model.

Although she avoided giving her resemblance, she was inspired by the graceful and regular features that the mirror reflected.

Hence, what you are admiring is the self-portrait of a young, confident painter smiling at us.

Of course, putting one’s face in a painting is a way to sign it.

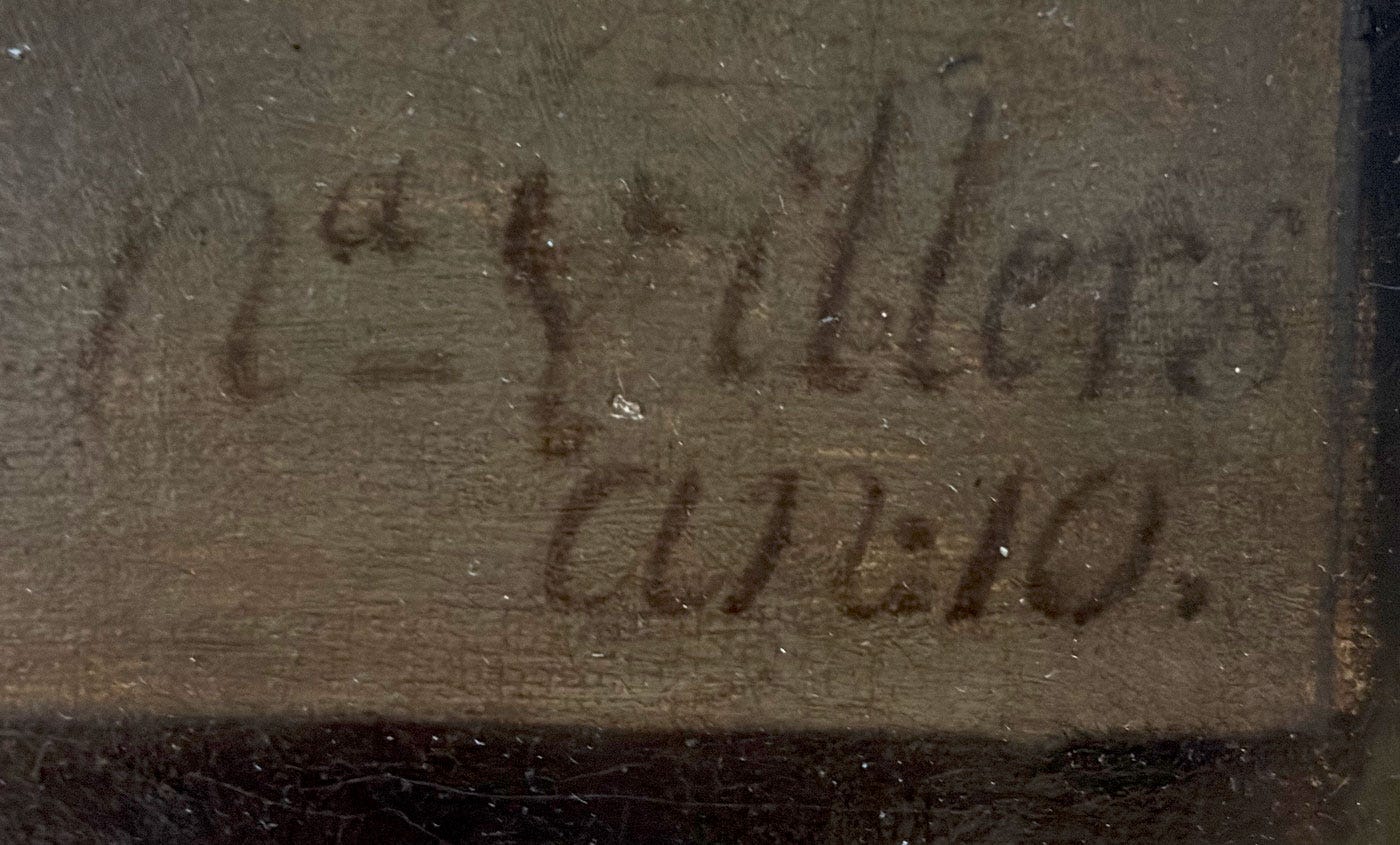

However, the Louvre portrait is the only known example of a signed Marie-Denise Villers painting.

Here is the signature:

Nisa Villers, An 10—Year 10 of the Revolution; 1802.

Confession time: until I asked myself how many painted portraits of the Louvre did smile, I did not pay much attention to Marie-Denise Villers’ painting.

As a Louvre School Graduate, supposed to know the entire museum like the back of his hand, I did overlook that painting my entire life.

That mistake has now been fixed.

Discovering a rare marvel was a Moment of Wonder for me, as I hope it would be for you.

The next story is about Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

Notes

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010067051

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010059447

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010060474

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010063406

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010066320

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010057822

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010279127

https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010061985

https://www.metmuseum.org/fr/met-publications/vigee-le-brun

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437903

Charles Sterling, A Fine "David" Reattributed, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Jan., 1951, New Series, Vol. 9, No. 5 (Jan., 1951), pp. 121-132.

Frieda van Emden; Judith Leyster, a Female Frans Hals; The Art World, Vol. 3, No. 6 (Mar., 1918), pp. 500-503.

https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/our-collection/our-masters/judith-leyster

https://www.thecollector.com/judith-leyster-woman-dutch-golden-age/

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6365026c/f23.image.r=Villers

https://www.journal18.org/issue2/through-a-louvre-window/#_ftn5