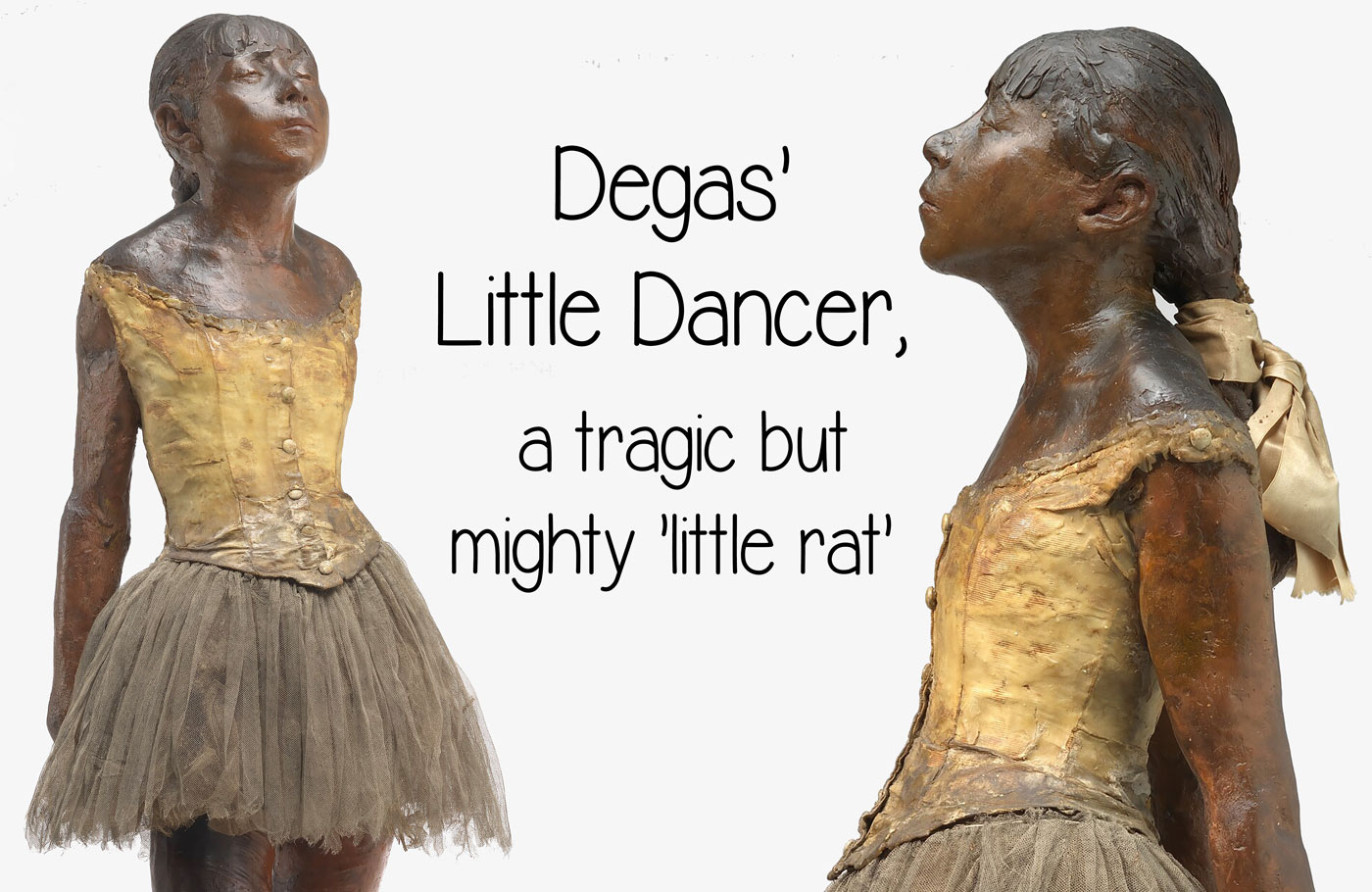

Degas' Little Dancer, a tragic but mighty 'little rat'.

From 'vicious, ugly beast' to masterpiece.

Dear reader, it is hard to understand why Impressionist paintings were rejected. We have already discovered how much scorn was thrown at Monet and others with "When Impressionism was seen as hideous daubs."

Discovered how, in the 1890s, the idea of accepting the most important Impressionist art collection assembled for free was hard to swallow.

That helped us realize how difficult it would be for a woman artist, Camille Claudel. This time, we turn the projector on the critics by discussing why they called Degas's Little Dancer a vicious, ugly beast.

This is going to be quite a ride from tragedy to wonder.

We enter the time machine, set it to Paris, 1881, and confront the experts with their own words.

Important for context: at the time, ballerinas were called 'little rats.' The label had two facets. The affectionate one depicts girls scurrying about the stage. And its derogatory side, as dirty animals living in sewers.

As we will see, the cats trying to catch the defenseless little rats were the sort of men who threw vitriol at Degas. Here is a selection of their criticism of the statue when Degas exhibited it.

Degas’ Little Dancer — a monkey

Your opera rat is part monkey, part Aztec, and part freak. If it were smaller, we would be tempted to lock it up in an alcohol preserve.

In the critic's mind, Aztec means 'Aztec mummy'; he describes the dancer as a mix between monkey, mummy, and freak.

Another critic called it a young monster chosen for its bestiality, that should be displayed in a zoology museum, like a freak specimen.

The Little Dancer — a vicious, ugly beast

One critic stated:

The vicious muzzle of this little, barely adolescent girl, this little flower of the gutter.

Another went further:

Fearsome, because she is without thought, she advances, with a bestial effrontery, her face or rather her little snout. Why is she so ugly?

Why is her forehead, half concealed by her hair, already marked, like her lips, with such a profoundly vicious character?

The ugliness of a face where all vices imprint their detestable promises.

The figure of vices? What the critics mean by 'little rat'

In our little time travel, we encounter a poet who clearly explains to us the meaning of the word 'little rat:'

Rat - name given at the Opera to little girls destined to be dancers. The age of the rat varies from eight to fourteen or fifteen years; a sixteen-year-old rat is a very old rat.

What a singular destiny that of these poor little girls, frail creatures offered in sacrifice to the Parisian Minotaur, this monster far more formidable than the ancient Minotaur, and which devours virgins by the hundreds every year without any Theseus ever coming to their aid!

The poet also tells us that the little rat's day is worse than that of a working horse or galley slave. Men wait for the little rat once the ballet is over. They are diplomats, journalists, respectable men.

The dancer takes the arm of her favorite, who takes her to supper and escorts her home or to his, depending on the circumstances.

Vice is in the eye of the beholder

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, dear reader, the past was often quite different from what we see in movies and television. Visiting the Opera Garnier in the 1880s was not as romantic as some imagined.

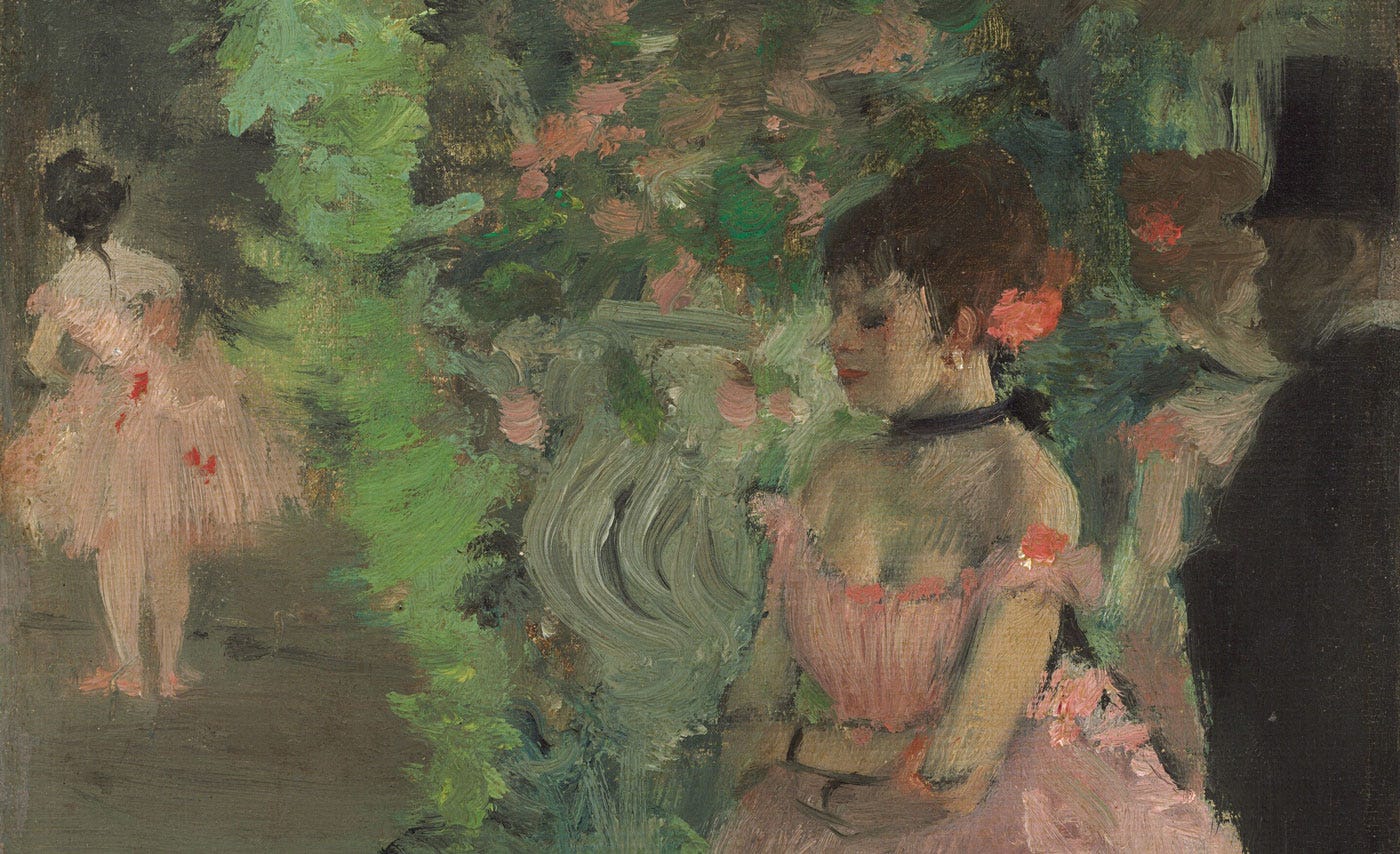

The Degas painting above depicts a wealthy subscriber. In those days, anyone who paid a costly Opera subscription could go backstage to see young dancers practicing.

The polite word for such a man was mentor or protector. Most of these dancers were very poor and had mothers pushing their daughters into the arms of the highest bidder. For some people, the reason for attending the opera was artistic delight.

For others, the enjoyment was that of the predator at the upscale cattle market, admiringly watching their prey.

Sorry to be blunt, this was hitting where it hurts. Daring to call a realistic statue of a dancer doing nothing more, nothing less than practicing her moves, and seeing vice was precisely a reflection of the critics' minds.

The teacher we see in the painting above is not a pervert with dirty thoughts, so he sees no vices in young girls dancing. The journalist or art critic who recoils in horror at the far too realistic image of a 'petit rat' acts as if he were caught with his pants down.

The Opera during the birth of Impressionism

Look at the painting above. This is the Masked Ball, and respectable men in top hats are unashamedly sampling the merchandise on offer.

Dear reader, now you see what the men who did their best to ruin the careers of Manet, Monet, Renoir, Rodin, and many others look like. And in quoting their own words, seeing a little dancer as a vicious, ugly beast, you understand what they meant.

The word is hypocrisy: nude figures are fine as long as they pretend to be Greek goddesses.

The 'terrible reality' that caused discomfort and embarrassment to the public and the experts is caused by forcing 'respectable' men to face up to their visits to the brothel and their lust for young girls. And that triggered their anger.

Degas never exhibited any other statue for the rest of his life. The Little Dancer, made of wax and real clothes, risked being forever damaged. Degas himself did not expect any of his wax statuettes to survive:

By the time I die, all this [my sculptures] will have destroyed itself, and that will be better for my reputation.

Had this happened, the model's identity would have been forever lost. Who was the Little Dancer?

A Little Dancer named Marie van Goethem

Marie van Goethem was born in Paris to Belgian parents in search of a better life. One of three sisters, their lives illustrate the swings of fate for a poor family. The eldest daughter, who did pose for Degas, spent time in prison for theft.

The youngest, who entered the Opera with Marie, pursued a career there until she became a respected dance professor. It shows that a few dancers could climb from the gutter to the top, but sadly, that was not to be Marie's destiny.

One of the last records we have of her is from a gossip newspaper:

Miss Van Goeuthen—fifteen years old, has an older sister who is supernumerary at the Opera and a younger sister in the Opera dance school—consequently she frequents the Martyrs Tavern and the Rat Mort.

The ominous word here is the tavern's name, 'le Rat Mort,' which means 'dead rat'. It was a bar where artists and bohemians spent the night. It was in the middle of the red-light district, and there is little doubt that Marie's widowed mother was prostituting her daughters.

Next, records indicate she was dismissed from the Opera for repeated tardiness. That is the last trace of Marie van Goethem. We do not know what happened afterward, and we can only hope that Marie fell into an anonymous life rather than end up one night in the ditch.

Her wax double, the original statue, and the sketches Degas did were the only traces of her appearance. Her name subsided into Opera records, but as one out of thousands, it was destined for the dustbin of history.

Yet, and this is where the good news comes, dear reader, Degas's hope that the wax figure would not survive did not come to pass.

From the gutter to the museum

Traditionally, a wax statuette is destroyed when transposed into bronze. It is not supposed to be kept, as it is very fragile. Case in point: when the Louvre was offered to purchase the wax original, curators deemed it worn out and failed to seize the opportunity.

In 1881, the wax was painted skin color, set with real hair, and wore genuine clothes. It was no different from the waxwork figures at Madame Tussauds or a strange doll. But Degas put it on a pedestal, inside a glass case, raising it to the status of art.

Elevating a 'vicious monkey' to the realm of classical art angered critics. They needed not worry; the Little Dancer remained tucked away until Degas died in 1917. From the 1920s, bronze casts of the Little Dancer were made, many ending up in museums worldwide.

Degas’ Little Dancer, a masterpiece that granted Marie eternity

Once in museums, no one looked at her as an ugly beast, a vicious figure, but as a graceful, realistic image of a young dancer practicing the same moves as many dancers do today. Art historians recognized it as a masterpiece, a major step toward modern art, for wearing actual clothes.

As illustrated here, we know little about Marie van Goethem, aside from the fact that she posed for Degas and was a dancer at the Opera. Degas' sketches and notebooks mention her name and address, which is how we know who the Little Dancer is. We lose her trace in the squalid Montmartre nightlife.

Her education was elementary, so one wonders if she even considered the effect that posing for Degas would have. The wax original, which she would have seen posing only a few meters away, was transposed into bronze and displayed in museums worldwide, granting her eternal life.

Yes, eternity. As we will see in the following story, 'From anonymity to eternity,' posing for a sculptor or painter is one step toward eternity. If a major artist records one's face and name, as Degas did, it will end up in a museum. Museums are places meant to preserve mankind's memory for posterity.

So, even if she did it to put food on the table, without realizing the sculpture's impact, the moments she spent posing for Degas made her eternal. Next time, dear reader, you get to see the statue in a museum, say her name, Marie van Goethem.

That makes her eternal, which I trust is a Moment of Wonder.

Sources

“Degas raconté par lui-même”, Le Temps, 11 Aout 1931.

Jules Claretie, “La vie à Paris: Les artistes indépendants”, Le Temps, 5 Avril 1881.

Élie de Mont, “L’Exposition du Boulevard des Capucines”, La Civilisation, 21 Avril 1881.

Paul Mantz, “Exposition des œuvres des artistes indépendants”, Le Temps, 22 Avril 1881.

Théophile Gautier, le rat, 1866.

The author translated and edited all original French sources for this story.