Leonardo da Vinci, the man behind the icon.

Meeting the real Leonardo, with direct testimonies from people who knew him.

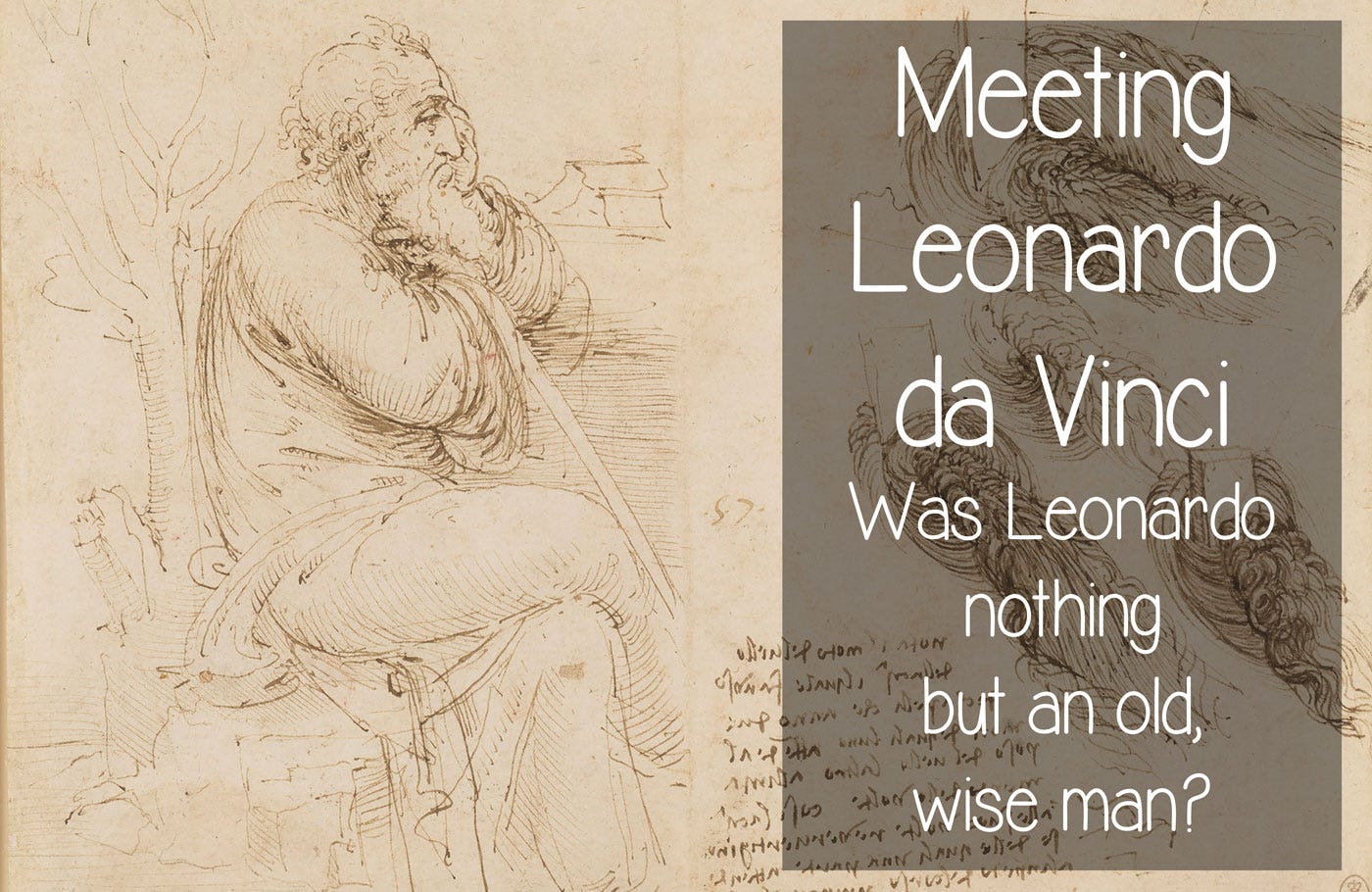

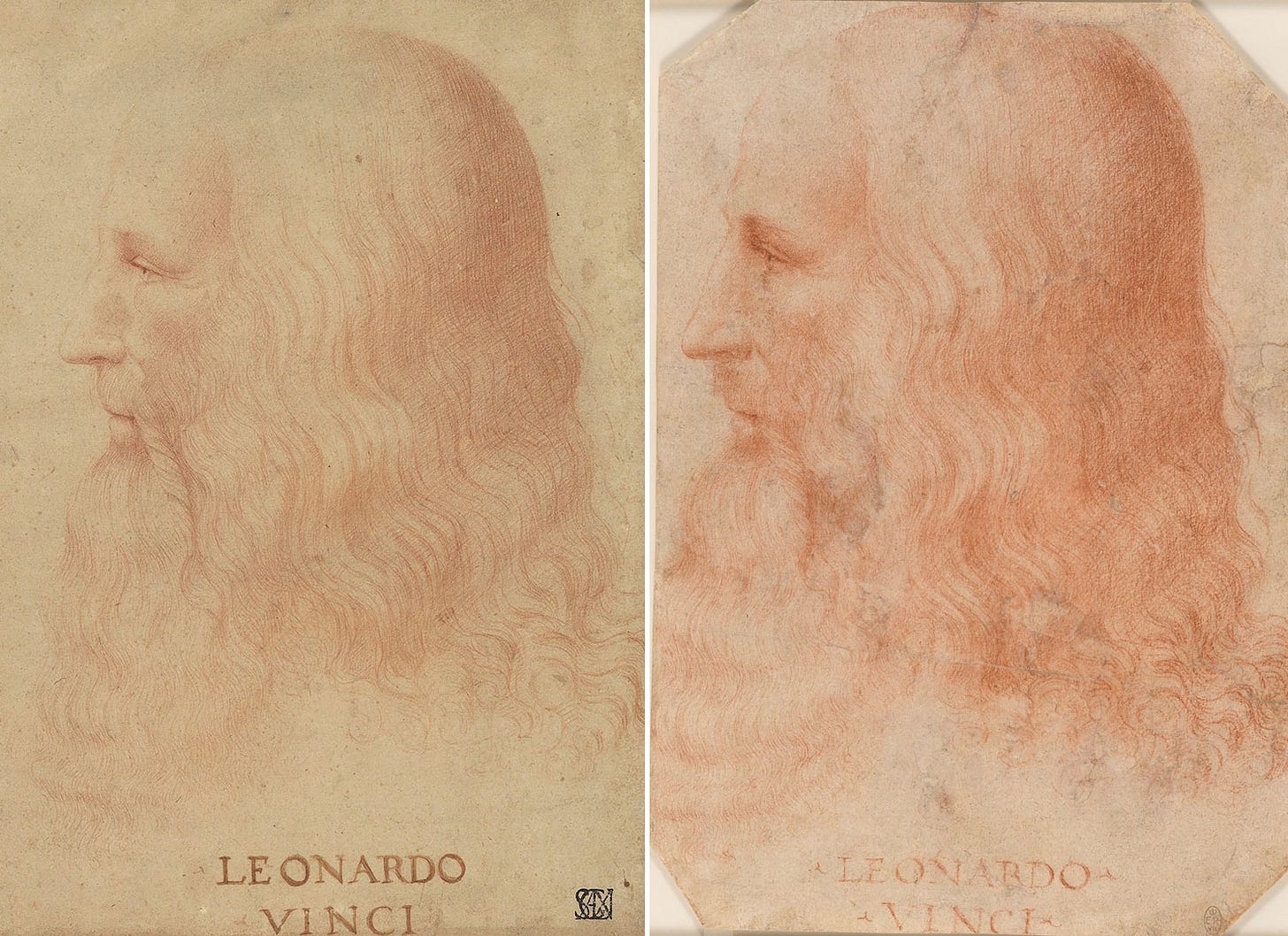

In the previous story, "Looking for Leonardo da Vinci," we discovered the rare portraits drawn during Leonardo's lifetime that helped us imagine what he really looked like.

Now, we meet the man behind the icon.

Was Leonardo always old and wise?

The only images that represent Leonardo as a living and breathing man were drawn when he was about 65 years old.

Dear reader, to meet the real Leonardo, we will travel back in time and ask the people who knew him.

Leonardo da Vinci's last years in France

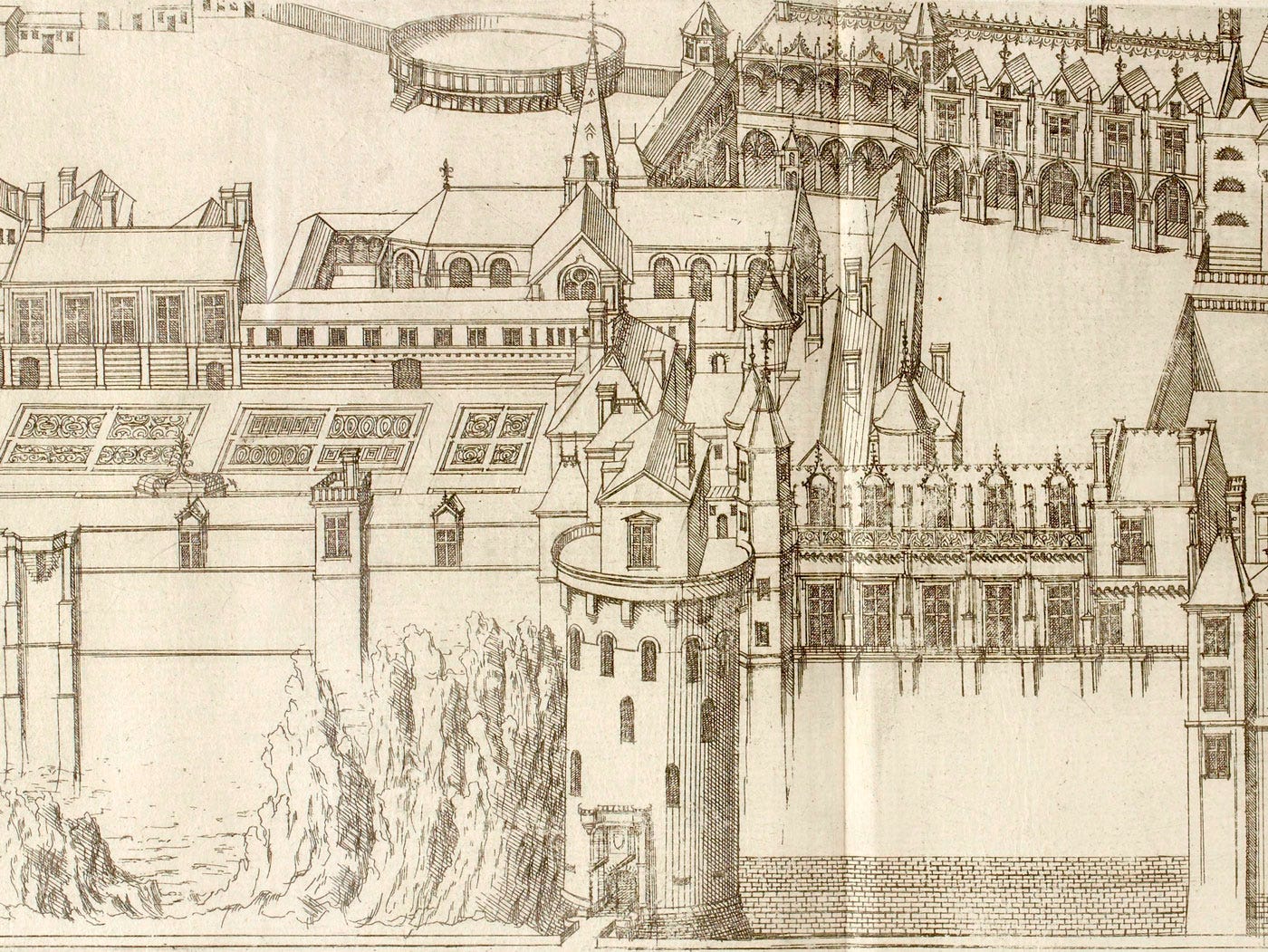

At age 64, Leonardo crossed the Alps to the Loire Valley. There, the young King Francis treated him with great reverence, calling him padre—father, a mark of respect—and appointed him the First painter, architect, and engineer to the King.

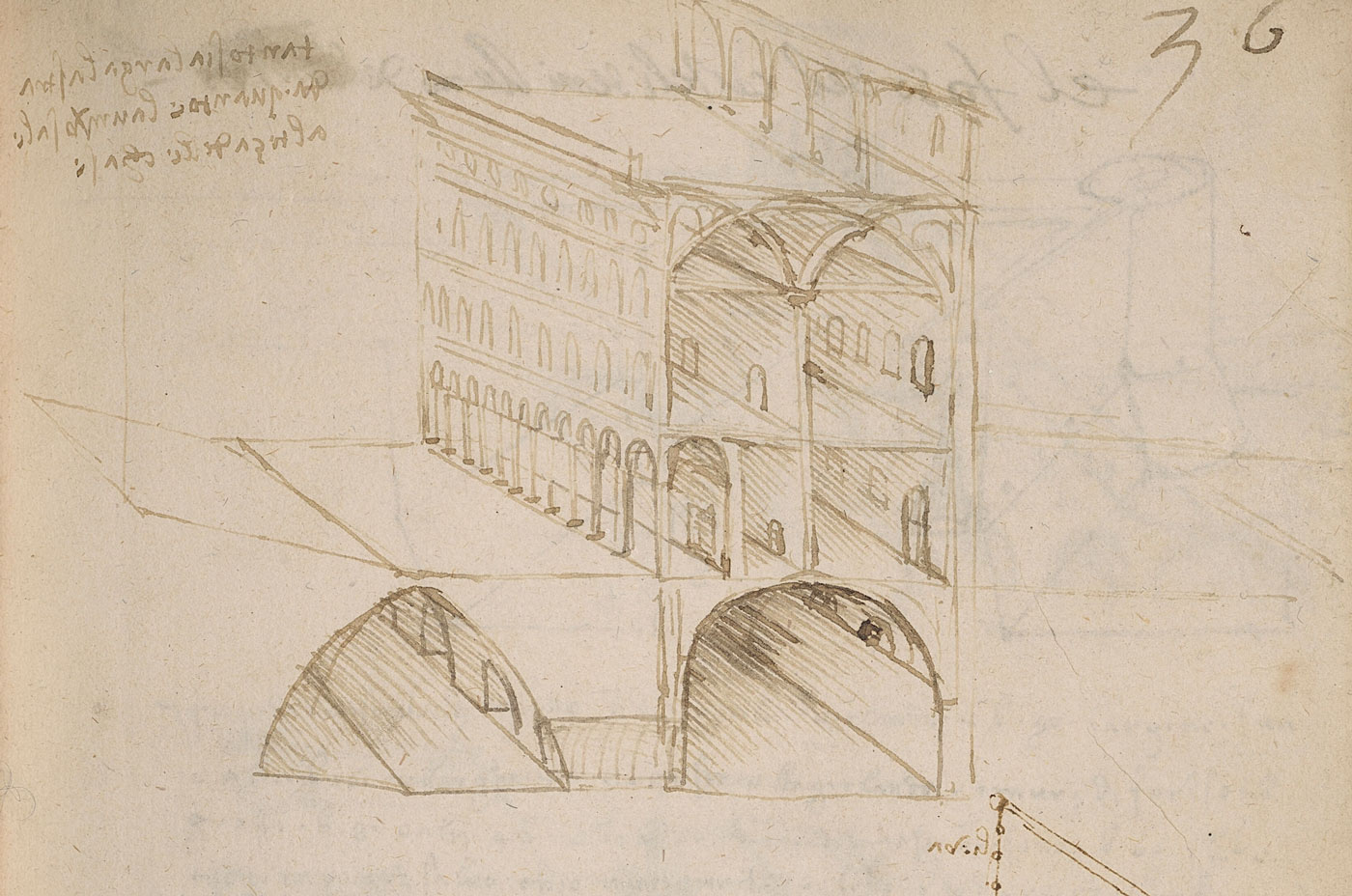

Leonardo was well-paid and lived in a small castle near the King's castle. The sketch above is part of his project for a vast royal castle with advanced hydraulic systems.

Only one contemporary witness described Leonardo's time in Amboise:

Messer Leonardo Vinci the Florentine, an old man of more than seventy years, the most eminent painter of our time.

The witness then describes three paintings, mourning that

One cannot indeed expect any more good work from him, as a certain paralysis has crippled his right hand.

Messer Leonardo can no longer paint with the sweetness which was peculiar to him, he can still design and instruct others.

And the many books by Leonardo

He has also written of the nature of water, and of diverse machines, and of other matters, which he has set down in an endless number of volumes, all in the vulgar tongue, which, if they be published, will be profitable and delightful.

The fate of those books will be told in “What really happened to Leonardo's drawings”.

Sorrow at Leonardo's death

The inevitable happened, and in May 1519, the wonders inside Leonardo's mind forever disappeared. The King accepted Leonardo's demand that he be buried inside the royal castle's chapel (the bell tower visible in the sketch above).

Melzi, the pupil who did the portraits, wrote to Leonardo's brother to announce the sad news:

It is impossible for me to express the grief that his death has caused to me.

Until the day when my body is laid under the ground, I shall experience perpetual sorrow.

Melzi added what may be the best line written about Leonardo:

His loss is a grief to everyone, for it is not in the power of nature to reproduce another such man.

Unless some mad scientist can merge Albert Einstein with Raphael, there indeed will never be another man like this.

Leonardo da Vinci according to the King of France

Twenty-five years later, the great sculptor Benvenuto Cellini, who worked for King Francis, testified that:

King Francis, being enamoured to an extraordinary degree of Leonardo’s great talents, took such pleasure in hearing him talk that he would only on a few days of the year deprive himself of his company.

I cannot resist repeating the words which I heard the King say about him:

He said that he did not believe that a man had ever been born who knew as much as Leonardo, not only in the spheres of painting, sculpture and architecture, but that he was also a very great philosopher.

Now, to make sense of how Leonardo differed from others, dear reader, we need to illustrate the reality in which Leonardo lived.

Leonardo's world was not like you saw it on television

We see Florence as the city of Botticelli's grace and of the rediscovery of the arts, sciences, and philosophy of Antiquity. It was indeed, but it was also the place and time when books and artworks were joyfully burned.

In the 1490s—peak Renaissance—the preacher Savonarola took over Florence. This is what he said about ancient philosophers:

The only good thing which we owe to Plato and Aristotle, is that they brought forward many arguments which we can use against the heretics.

Yet they and other philosophers are now in Hell. An old woman knows more about the Faith than Plato.

It would be good for religion if many books that seem useful were destroyed.

He organized two Bonfires of Vanities in 1497 and 1498. A large pyramid-shaped structure was built containing:

Sculpted figures of the most beautiful women of antiquity and of the most excellent proportion, both Roman and Florentine, portrayed by the great masters of sculpture, such as Donatello and the like.

Sculptures of great value and paintings of admiable beauty.

The books of poets and all sorts of lasciviousness, both Latin and vernacular... Petrarch, Dante, Boccaccio, and similar disgraceful things.

The whole thing was torched. Fortunately, Leonardo was in Milan during these years.

Dear reader, now it starts to make sense that there is a wide gap between legend and reality. Let's see if Leonardo was nothing but an old wise man.

Leonardo da Vinci, the man behind the icon

Below are extremely rare testimonies from people who knew Leonardo, not people who wrote long after his death. They give us an opening to the person behind the legend:

His charm of disposition, his brillancy and generosity were no less than the beauty of his appearance.

His genius for invention was astounding, and he was the arbiter of all questions regarding beauty and elegance, especially in pageantry.

He sang beautifully to his accompaniment on the lyre to the delight of the entire court.

There's more, from another witness

Beautiful in person and aspect, Leonardo was well-proportioned and graceful.

He wore a rose-colored cloak, which came only to his knees, although at the time long vestments were in custom.

His beard came to the middle of his breast and was well-dressed and curled.

Now, we rely on Vasari, the man who compiled most of what we know of Leonardo's life.

Leonardo was a practical joker

To a very strange lizard, found by the gardener of the Belvedere, he fastened some wings with a mixture of quicksilver made from scales scraped from other lizards, which quivered as it moved by crawling about.

After he had fashioned eyes, a horn, and a beard for it, he tamed the lizard and kept it in a box, and all the friends to whom he showed it fled in terror.

He played with inflating balloons made of animal guts.

He had placed in another room a pair of smith's bellows to which he attached one end of these guts so that by blowing them up he filled the entire room, which was enormous, so that anyone standing there would have to move to one corner.

A musician & slam poet

Not the kind of man to do things halfway, Leonardo created his own lyre and played it to acclaim. He was also a poet:

He was the best declaimer of improvised poetry in his day.

The greatest geniuses accomplish more when they work less

He set about learning many things and, once begun, he would then abandon them.

We might say that he owned nothing and worked very little.

He began many projects but never finished any of them, feeling that his hand could not reach artistic perfection in the works he conceived, since he envisioned such subtle, marvellous, and difficult problems that his hands, while extremely skilful, were incapable of ever realizing them.

We also have a first-hand witness who states he saw Leonardo work on a statue, stop, rush to put one or two touches of paint to the Last Supper, and then rush back to the statue...

Don't mess with Leonardo da Vinci

You know already that the Last Supper in Milan is a universal masterpiece. In reality, the monk complained that Leonardo was lost in thought instead of working. Leonardo's answer was:

The greatest geniuses sometimes accomplish more when they work less, since they are searching for inventions in their minds.

Leonardo proposed using the monk's face as a model for Judas. Don't mess with geniuses.

Leonardo wrote a CV to get a job

He sent his CV to the Duke of Milan, as a 40-year-old man, a ten-point list of his skills. Points 1 to 9 are about creating war machines.

And then, point 10, where he states he is also an architect and can create marble and bronze sculptures. And the very last point:

In painting, I can do everything possible as well as any other, whosoever he may be.

Plain English translation: unlike the legend, the reality of Leonardo's life is that politicians of the Italian Renaissance cared more for war than art.

The line about 'by the way, I also paint' is like the tiny line at the end of a contract you're not supposed to read.

'I am no penny painter!'

To further illustrate the distance between myth and reality, we find many complaints about insufficient pay, whether from the Duke of Milan or the ruler of Florence.

The best line—Leonardo's own words—is an argument with monks about the value of a painting.

(The monks) are not experts in such matters, and the blind cannot judge colors.

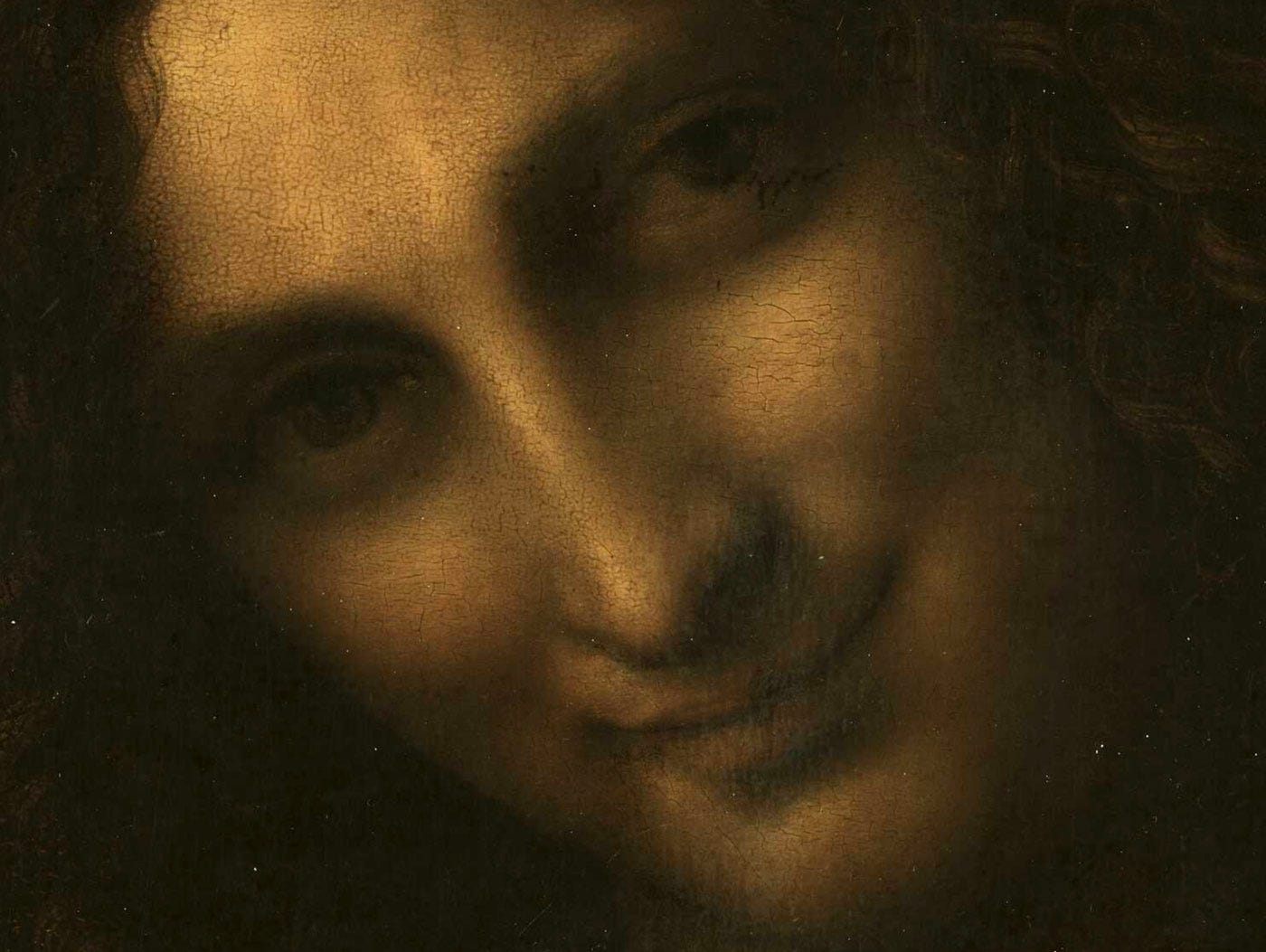

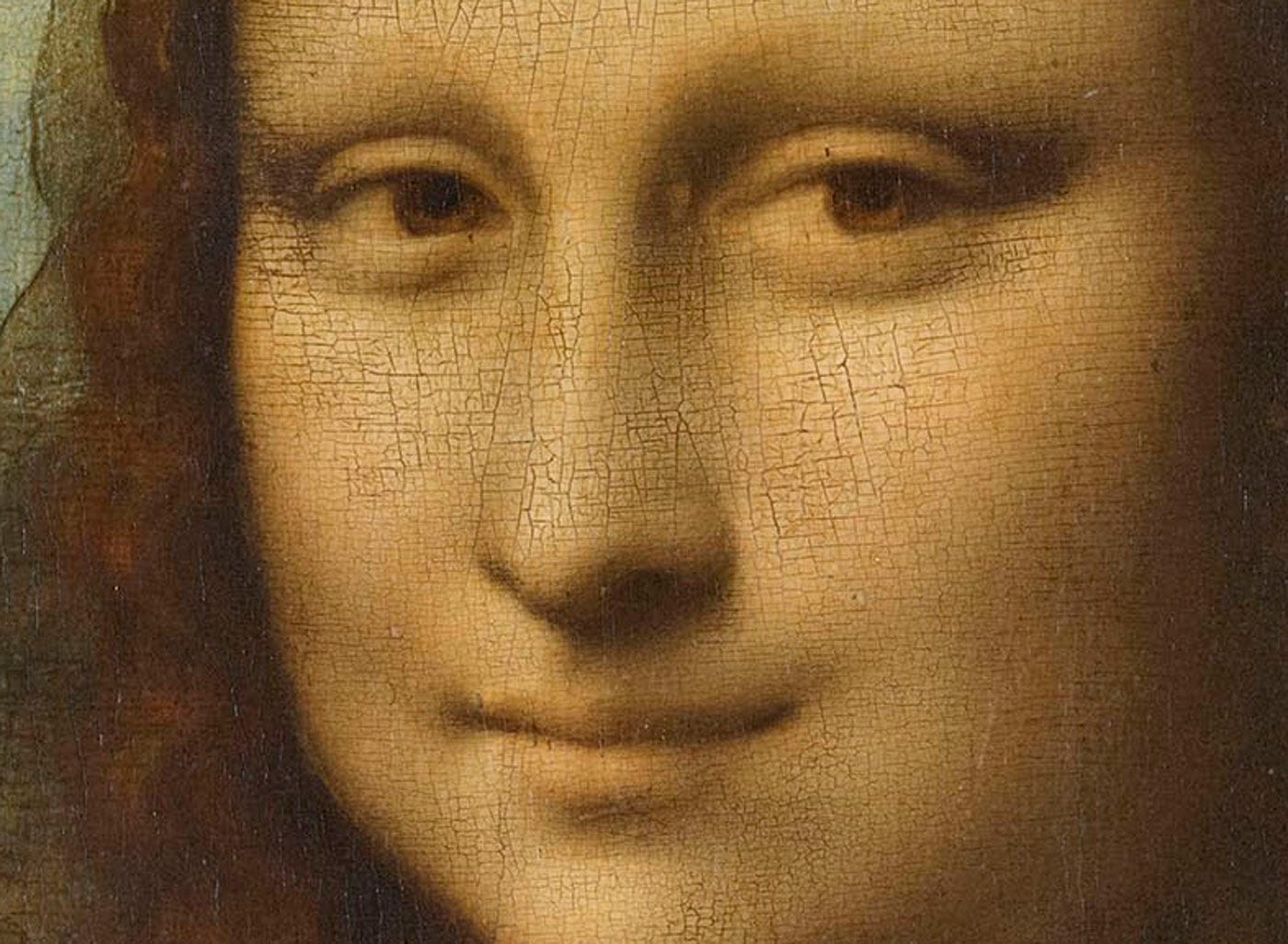

Leonardo da Vinci, the painter of smiles

Dear reader, telling you about the Bonfires of Vanities was to help you realize the Renaissance was not always an age of joy.

A previous story, 'When Paintings Smile At You,' explained that the number of Renaissance portraits that smile is somewhere close to zero.

With one glaring exception, Leonardo da Vinci. We even know that this was a subject that interested him from an early age

In his youth, he made in clay the heads of some women laughing.

And that the fact he focused on smiling had:

Their origin in Leonardo's intellect and genius.

Enough blathering; below is a selection of paintings that do the talking.

Dear reader, feel free to find out how many Renaissance paintings depict smiles.

Then, take another good look at Leonardo's paintings. Notice how many of them smile and enjoy a great Moment of Wonder.

Notes

Paolo Giovio, Anonimo Gaddiano, Francesco Melzi, Antonio de Beatis; in Ludwig Goldscheider, Leonardo da Vinci, 1959.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the artists.

Benvenuto Cellini translated for this article from the French; edition Oeuvres complètes de Benvenuto Cellini.

Selected Writings of Girolamo Savonarola, Religion and Politics, 1490-1498; Yale University Press; La vita del Beato Ieronimo Savonarola, previously attributed to Fra Pacifico Burlamacchi, Chapter XL, How he set fire to all the vanities.